Introduction

Supplemental Insurance

In many countries with public health insurance coverage, individuals have the option to purchase additional coverage from private health insurers to supplement public coverage. This additional coverage can either duplicate public coverage or fill in gaps (supplement) in the public plan, such as covering services outside the public benefit package or filling in cost-sharing gaps in the public coverage. The Organization for Economic Co operation and Development (OECD) defines supplementary coverage as

Private health insurance that provides cover for additional health services not covered by the public scheme. Depending on the country, it may include services that are uncovered by the public system, such as luxury care ,elective care, long-term care, dental care, pharmaceuticals, rehabilitation, alterative or complementary medicine, etc., or superior hotel and amenity hospital services.

Supplementary policies are commonly held in many OECD countries, including Australia, Canada, Germany, Ireland, Switzerland, the Netherlands, the UK, and the US Medicare population. Although the precise rules vary by country, the key motivation is that many types of public insurance leave policy holders with substantial potential liability for out-of-pocket expenses (Figure 1).

What Does Supplemental Insurance Cover?

Supplemental insurance coverage varies depending on the rules of the particular country as to what it is allowed to pay for and what the public program includes. Typically, coverage may include cost sharing for publicly provided services (e.g., France, USA), coverage for services outside the public benefit package (e.g., Canada, Germany), particularly dental services (e.g., Australia, Japan, UK), and superior amenities, such as private rooms in hospitals (e.g., Italy, UK). In some situations, supplemental coverage may also serve to provide swifter access to some services (e.g., Norway, UK).

What, precisely, supplemental insurance covers varies not only across countries but also for particular countries over time as the rules for what can be covered and the public benefit packages change. For example, supplements for the Medicare program in the USA often provided coverage for prescription drugs before 2006; when prescription drug coverage was added to the benefit package in 2006, supplemental policies often dropped that benefit. Currently, discussions are under way in the USA to limit the amount of cost-sharing supplemental insurers can cover.

Examples of what supplemental insurance policies cover in different countries are as follows:

- Australia: medications not covered by the public system; dental services, aid, and appliances; copayments for covered services;

- Canada: prescription drugs; dental care; nonhospital institutions (long-term care), vision care, and over-the-counter medications;

- France: dental and vision services, and copayments for covered services;

- Germany: uncovered services; access to better amenities and some copayments;

- Italy: over-the-counter drugs, dental care, access to better hospital amenities, and improved provider choice;

- Japan: dental services;

- Netherlands: adult dental care;

- New Zealand: copayments and cost sharing, elective surgery in private hospitals, private outpatient specialist consultations, and faster access to nonurgent treatment;

- Norway: shorter waiting times for publicly covered elective services.

Duplicative Coverage

In some situations, coverage can be purchased that effectively duplicates or replaces the publicly provided coverage. This then provides a private alternative to the public system. OECD defines duplicative coverage as

Private insurance that offers coverage for health services already included under public health insurance. Duplicate health insurance can be marketed as an option to the public sector because, while it offers access to the same medical services as the public scheme, it also offers access to different providers or levels of service. It does not exempt individuals from contributing to public insurance.

Examples of this approach to supplemental insurance include Australia, Ireland, and the UK. Some countries, such as Canada, explicitly prohibit duplicative coverage.

Duplicative coverage is distinct from supplemental insurance in a number of different ways. Most importantly, duplicative coverage is intended to replace the public coverage – it is essentially an opt-out from the public system. In contrast, supplemental insurance is intended to enhance the public program and improve it by either providing more extensive coverage, reducing financial risk, or providing better access to publicly funded services.

Controversies Regarding Supplemental Insurance

Supplemental insurance has been the subject of some criticism. One of the principal criticisms is that if supplemental insurance provides valuable financial protection, it implicitly suggests that the public system is inadequate because additional coverage is necessary. If additional coverage is necessary, this then implies that there are important gaps in the public coverage. Supplemental insurance, because premiums are not based on income, thus allows higher income individuals better financial protection than lower income individuals, which undermines the goal of public coverage for health care.

Another criticism is that in some cases, the supplementary coverage can have problematic interactions with the public coverage. This can involve risk selection, increases in public costs due to the presence of the supplemental policy, and/or distortions in terms of access, such as wait times, to public care that serves to feed the demand for privately insured care. For example, in both France and the USA, studies have found that the removal of cost sharing by supplemental insurance leads to the increased use of services in the publicly funded program.

Supplemental Insurance In The USA

In the USA, supplemental insurance is most common among beneficiaries of the publicly funded Medicare program, and is sometimes referred to as ‘Medigap’ plans. Medicare supplemental insurance can either help pay for Medicare cost sharing or provide coverage for services not included in the Medicare benefit package, such as health insurance outside the USA.

The Value Of Supplemental Insurance Plans

Medicare is the largest publicly provided health insurance program in the USA, with approximately 49 million enrollees in 2012. Although there are a number of ways to gain Medicare eligibility, the most common is through age eligibility, which occurs at age 65. Although Medicare covers many medical services, it often does not cover the services in full. For example, in 2012, Medicare Part A would pay for the full cost of a hospitalization for days 1–60, with a $1156 deductible (equal to the cost of the first day of the hospitalization). For the typical Medicare beneficiary – with a median income of $22 000 – Medicare cost sharing creates a substantial financial liability. If a Medicare beneficiary used all of the Part A (inpatient) covered services in 2012, the total cost sharing would be approximately $54 910, which includes a $8670 copay for hospital days 61–90, a $34 680 copay for hospital days 91–150, and $11 560 for skilled nursing facility (SNF) for days 21–100. For hospital stays beyond 150 days and SNF stays beyond 100 days, there is generally no coverage.

Medicare gaps are of two different types:

- Cost sharing for covered services

- Benefit limits

For example, for Medicare Part B, there is a $100 annual deductible plus a 20% copayment for covered services. There are also many services outside the benefit package, such as eyeglasses and hearing aids. Supplemental insurance can address either of these program limitations.

Sources Of Supplemental Insurance Plans

There are two main sources of private supplemental insurance plans: employers and individual purchase. Individual purchase plans (which are often referred to as the ‘Medigap’ plans) are designed to be integrated with Medicare; in contrast, employer supplements are often extensions of medical insurance provided for active workers and thus not optimally designed for coordination with Medicare. Employer plans are provided to retired workers, with eligibility rules that often mirror early retirement rules. Typically, eligibility is dependent on the employee’s age and length of service with the firm.

For employer plans, Medicare is considered the primary payer with the supplemental/employer plan serving as the secondary payer. Although there are several different methods used to coordinate benefits, with the most common method being carve out, beneficiaries still pay some portion of Medicare deductibles and thus have higher cost sharing than true Medigap plans. However, employer supplementary plans are more likely to include coverage for noncovered Medicare benefits, such as chemical dependency treatment, vision coverage, dental coverage, and ‘catastrophic expenses’ caps, whereby the total out-of-pocket liability is capped.

The main alternative for Medicare beneficiaries without access to group coverage is individually purchased plans, often called ‘Medigap’ plans. Medigap plans date back to the beginning of Medicare, in the mid-1960s, and have been extensively regulated since the 1990s. During congressional hearings before the Congressional Select Committee on Aging in 1978, extensive marketing abuses were described. These abuses by the policy sellers included using high-pressure sales tactics, misrepresentation by the issuer of the policy, misrepresentation of policy contents and competitors’ policies and ‘rollover’ of plans, whereby subscribers were forced to change policies to increase policy commissions.

Subsequent to these hearings, two different regulatory reforms of the individual supplemental insurance market were enacted. The first, in 1980, was the Voluntary Certification of Medicare Supplemental Health Insurance Policies, commonly known as the Baucus Amendment (Public Law 96–265, Sec. 507). The Baucus Amendment addressed the abuses of the market by setting minimum coverage standards, outlawing the knowing sale of multiple policies, and requiring higher loss ratios. The amendment was not considered to have successfully achieved its policy goals. Hearing in the 95th Congress suggested that many of the same issues remained, largely due to the voluntary nature of the Baucus Amendment requirements. Thus, a second reform was enacted in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA-90), Section 1882 of the Social Security Act. Unlike the Baucus Amendment, the OBRA-90 reforms were mandatory and changed the industry significantly.

OBRA-90 increased minimum loss ratio requirements for the plans, prevented the sale of duplicate plans, established consumer counseling programs, limited agents’ commissions, and required a 6-month open-enrollment period. This period allowed beneficiaries to purchase Medigap policies without regard to health status, with guaranteed renewal of the policy. The ‘enrollment window’ opens when the beneficiary initially enrolls in Part B. After expiration of the 6-month window, some policies (although not all policies) become experience rated or medically underwritten. Finally, OBRA-90 required the creation of model policies, which were the only new Medigap policies allowed to be sold after 30 July 1992.

Standardization Of ‘Medigap’ Plans

The standardization requirement limits the Medigap plans that can be sold to the approved plans. These approved plans have precisely the same benefit structure regardless of seller. Initially, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners was charged with the development of 10 model policies. The initial model policies provided a range of options, although all plans were required to cover a set of ‘core benefits,’ which include coverage for the Part A hospital daily copayments for days 61 through 150, the 20% Part B coinsurance on physician charges, and the first three pints of blood received each year, as well as coverage for an additional 365 days of hospital care. The model policies (typically labeled policies ‘A’ through ‘J’) originally featured various combinations of eight benefits: the Part A deductible, the Part B deductible, coverage for the SNF copayment, foreign travel, prescription drug coverage, preventive medical care, and coverage for at-home recovery. Only 2 of the 10 plans covered the Part B deductible (C and F), but together these two plans included more than half the market in the 1990s and 50.9% in 1994. The most common benefits originally were the Part A deductible (included in 9 of the 10 model policies, B through J) and coverage for the SNF copayment and foreign travel (both included in C through J).

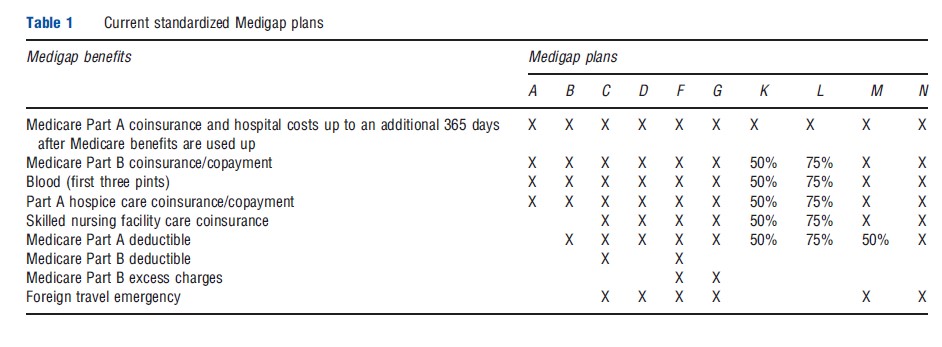

Congress has amended the model benefits a number of times, most recently in the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) of 2003. After MMA, there are eight different benefits plus the ‘core’ benefits distributed across 10 plans. The core benefits focus on Medicare Part A copayments for extremely long hospitalizations. All of the plans offer some form of coverage for Medicare Part B cost sharing, the first three pints of blood during a hospitalization (uncovered by Medicare), and the Part A hospice care coinsurance. Plans M and N became available for the first time in June of 2010, at which time plans D and G were modified and Plans E, H, I, and J could no longer be sold, although beneficiaries with those plans could continue coverage (Table 1).

Other benefits include the SNF coinsurance (eight plans), the Part A deductible (nine plans), the Part B deductible (two plans), Part B excess charges (two plans), and coverage for emergencies during foreign travel (six plans).

The two most popular plans in 2010 were Plan F (44% of enrollees) and Plan C (14%) . These are also the most comprehensive plans offered. Both Plans C and F will be revised in 2015 to include some cost sharing for Part B services. Participation in the new plans – Plans K–N – is extremely low. Combined, Plans K and L account for less than 1% of plan purchases.

Premium Levels And Regulation

Federal regulations establish two different time periods when there is ‘guaranteed issue’ of Medigap premiums, i.e., time periods when insurers may not decline a beneficiary. The first is during the first 6 months after initial enrollment into Medicare Part B. The second time period covers a series of transitional periods between different types of Medicare coverage, such as between Medicare Advantage (MA) and standard fee-for-service. Medical underwriting is allowed, but is generally limited to age, gender, and smoking status.

Premiums are generally regulated at the state level. Seven states required ‘community rating’ for Medigap policies in 2010. Community rating requires a single premium for all enrollees in the plan. Four states generally use ‘issue age’ rating, where the premium depends on the age of initial enrollment. The remainder of states use ‘attained-age’ rating, whereby the premiums depend on the current age of the policy holder. An ASPE analysis of premiums found wide variation across states, with premiums in the most expensive state (New York) nearly double that of the least expensive state (Michigan). During the decade between 2001 and 2010, average premiums increased 3.8% per year. In six of those years, the increase in Medigap premiums was less than that of total Medicare spending. This trend holds within plan types.

Demand For Supplemental Insurance ‘Medigap’ Plans

Medigap insurance is generally demanded by individuals who are more affluent. Research has found that those buying Medigap plans tend to have higher family income and other financial assets; to be younger, white, and married; and to have more education and a usual source of care. Evidence regarding age and health has been mixed, with some studies finding higher rates of purchase associated with better health and other studies the opposite. It appears that the relationship between the beneficiary’s health and supplemental insurance decision is dependent on knowledge of Medicare. In general, Medicare beneficiaries are badly informed about both Medicare design and insurance. However, chronically ill beneficiaries often have enough exposure to the health-care system to become well informed about Medicare’s limitations. Thus, the relatively better informed chronically ill beneficiaries are more likely to buy insurance, whereas those without chronic illnesses are not, regardless of self-rated health.

Other Sources Of Coverage

There are also several other sources of coverage available to select groups of Medicare beneficiaries. First, some Medicare beneficiaries are also eligible for Veteran’s Administration (VA) benefits. In 2004, 13% of Medicare-only beneficiaries (without supplemental insurance) identified a VA facility as their primary source of care. The services provided at VA and military facilities are generally not charged to either the individual receiving the services or to Medicare.

Second, some Medicare beneficiaries are also eligible for Medicaid. There are a number of different Medicaid programs available, depending on income level, but most at least pay for Medicare’s cost sharing and some provide coverage beyond the Medicare benefits package (‘wrap-around benefits’).

Supplemental Insurance And Medicare Advantage Plans

Medigap enrollment has declined markedly since 2006, when Medicare Part D came into effect. Part D provides prescription drug coverage and allows Medicare beneficiaries to select drug plans. The drug plans can be either ‘stand-alone’ plans or part of a Medicare managed care product, referred to as ‘Medicare Advantage’ (MA). MA plans are fully capitated health plans that serve much the same purpose as Medigap plans in that they help reduce Medicare cost sharing and provide additional benefits beyond the standard Medicare benefit package.

MA plans have existed in some form since 1983. The most valuable benefit offered by MA plans was prescription drug coverage, the value of which was diluted by MMA and Part D. However, after 2006, Medicare beneficiaries began switching in large numbers to MA plans from Medigap plans. Total Medigap market share declined from 25% in 2003 to less than 20% in 2010, whereas MA enrollment climbed from 11% to 25% in the same time frame.

Effect Of Supplemental Insurance Plans On Medicare Spending

There is an extensive literature on the effect of supplemental insurance on Medicare spending. The theory is that by lowering the out-of-pocket price of medical care, the quantity demanded of care will increase. This basic application of demand theory has extensive empirical evidence supporting it, including findings from the RAND health insurance experiment, a randomized controlled trial of the effect of cost sharing on the use of medical services from the 1970s. Over the past 25 years, there have been more than 15 studies on the effect of supplemental insurance on Medicare spending. The results of these studies vary markedly depending on the empirical methodology, data, and approach to controlling for adverse selection.

Adverse selection is a particular problem for the empirical estimation of the effect of supplemental insurance on Medicare spending. Theoretically, one would expect that higher risk individuals would be more likely to buy supplemental insurance because it holds greater value for individuals at greater risk of medical events. Showing a positive relationship between the purchase of supplemental insurance and Medicare spending thus is consistent with both adverse selection (higher cost individuals buy supplemental insurance) and demand (supplemental insurance leads individuals to become higher cost).

Empirically, studies have found effect sizes varying from zero (no effect) to a 33% increase in Part A spending and a 42% increase in Part B spending. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that individuals with Medigap policies use 25% more Medicare services than those with no supplemental insurance and 10% more than those with employee-sponsored insurance (which has higher cost sharing than Medigap plans). CBO bases its estimates both on an analysis of the supplemental insurance literature and on the results of the RAND health insurance experiment.

References:

- ASPE (2011). Variations and trends in Medigap premiums. Washington, DC: Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Health Policy.

- Atherly, A. (2001). Medicare supplemental insurance: Medicare’s accidental stepchild. Medical Care Research and Review 58(2), 131–161.

- Buchmueller, T., Couffinhal, A., Grignon, M. and Perronnin, M. (2004). Access to physician services: Does supplemental insurance matter? Evidence from France. Health Economics 13, 669–687.

- Commonwealth Fund (2012). International profiles of health care systems, 2012. New York: The Commonwealth Fund.

- Finkelstein, A. (2004). Minimum standards, insurance regulation and adverse selection: Evidence from the Medigap market. Journal of Public Economics 88, 2515–2547.

- Lemieux, J., Chovan, T. and Heath, K. (2008). Medigap coverage and Medicare spending: A second look. Health Affairs 27(2), 469–477.

- Maestas, N., Schroeder, M. and Goldman, D. (2009). Price variation in markets with homegenous goods: The case of Medigap. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper 14679. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/ w14679 (accessed 06.11.12).

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Private health insurance in OECD countries. Paris: OECD Health Project series 2004.