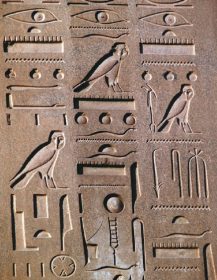

Egyptology is defined as the study of Ancient Egypt from the Badarian, circa 4500 BCE, to the Muslim invasion of Egypt in AD 641. (Identified in Upper Egypt by Brunton and Caton Thompson in 1928, the Badarian is contemporary with Fayum A in Lower Egypt.) This brought the “Great Tradition” cultural practices that had coalesced during Egyptian civilization’s 5,000-year existence to an end (pyramid building and other related monumental architecture, worship of the pantheon of Egyptian deities, dynastic succession, hieroglyphic writing, and mummification).

Egyptology should not be confused with “Egyptomania,” which refers to the fascination with “all things Egyptian” that took place after Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Tutakhenaten (who ceremonially changed his name to Tutankhamun shortly before his death), in the early 1920s. In this case, “Egyptomania” disrupted the systematic study of the artifacts by trained Egyptologists; bizarre interpretations of ancient Egyptian civilization remain with us today as a result (for example, the popular book Chariots of the Gods claimed that the pyramids were probably built by extraterrestrial beings, not by the indigenous people of Africa). However, the general public’s interest is certainly beneficial to Egyptology; few patrons can forget the impact of an Egyptian exhibit after visiting a museum like the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Cairo Museum. Remarkably, Ancient Egyptian civilization continues to be compelling, and relevant, in the postmodern world.

A History of Egyptology

Although Athanasius Kircher made a valiant attempt to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs in the mid-1600s, the modern phase of the study of Ancient Egypt is believed to have commenced after Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Egypt in 1798. Napoleon employed a number of artists and scholars, an estimated 167 in total, who formed the Commission des Arts et des Sciences, which included Claude Louis Berthollet, Gaspard Monge, Jean Michel Venture de Paradis, Prosper Jollois, Edmé François Jomard, René Edouard Villers de Terrage, and Michel-Ange Lancret; more than 30 from the commission died in combat or from disease. A new organization to focus on the study of Egypt, the Institut d’Egypte, was formed by Napoleon in August of 1798, with Gaspard Monge serving as its president. Baron Dominique Vivant Denon (1742-1825) was urged to join Napoleon’s expedition by his protectress Joséphine de Beauharnais, who would later marry Napoleon. Denon was a diplomat, playwright, painter, and renowned society conversationalist; his drawings of Medinet Habu are considered to be some of the most important in the history of Egyptology. Baron Joseph Fourier (1768-1830), who was an outstanding mathematician, facilitated the publication of Description de l’Egypte upon his return to France, and he held a number of prestigious posts, including prefect of the Isère Départment, in Grenoble, and Director of the Statistical Bureau of the Siene; Fourier’s publication represents an early attempt at compiling the tremendous amount of Egyptian material that was being discovered apace, making it widely available for other scholars to examine.

The British invaded Egypt shortly afterward and took possession of the priceless “Rosetta stone,” which had been discovered in 1799 near a city known as Rashld (meaning “Rosetta”), in 1801 when the French capitulated. The Rosetta stone was inscribed with three scripts—Egyptian hieroglyphic, Egyptian demotic, and Greek—thus Greek served as a conduit between the ancient Egyptians and the modern world. Thomas Young, a British physicist who had mastered 12 languages by the time that he was 14 years old, is responsible for some of the first creditable decipherments of ancient Egyptian writing, and he shared his findings with Jean F. Champollion, who later became famous as the preeminent figure of the decipherment effort.

A multitalented circus performer, strongman, and artist-turned-explorer named Giovanni Battista Belzoni (1778-1823) conducted archaeological excavations at Karnak between 1815 and 1817, and he entered Khafre’s pyramid at Giza in 1818, making him the first known person to enter the temple in modern times. In 1820, Belzoni published Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries Within the Pyramids, Temples, Tombs, and Excavations, in Egypt and Nubia. Belzoni’s association with Henry Salt, the British Consul General who had retained him to procure Egyptian antiquities for the British Museum, often causes scholars to regard him as a treasure hunter. Belzoni’s lack of “scholarly” credentials and his questionable archaeological agenda generate a measure of concern and derision among Egyptologists. Girolamo Segato (1792-1936) went to Egypt in 1818 as well, and he crossed Belzoni’s path, uncovering elusive artifacts that had been overlooked. Segato was a chemist, naturalist, and draftsman, and he was the first person to enter the Step Pyramid of Djoser in modern times (the pyramid had been plundered, presumably in antiquity, like most of the pyramids). Segato was a prolific map-maker, in the service of Ismail Pasha, with his work leading him well into the Sudan, where he encountered the Kingdom of Chiollo and Wadi Halfa during a 40-day walk. Although most of Segato’s drawings were lost to fire and his Egyptian treasures lost to shipwreck, he published Pictoral, Geographical, Statistical, and Cadastral Essays on Egypt in 1823, and Atlas of Upper and Lower Egypt with Domenico Valeriano in 1837.

The most noteworthy contributors to the establishment of Egyptology as an academic discipline are Ippolito Rosellini, diplomat, explorer, and collector Bernardino Drovetti (1776-1852), Emmanuel vicomte de Rouge, Jean Jacques Rifaud (17861845, Drovetti’s artist), James Bruce (1730-1794), Owen Jones, Samuel Birch, Ludwig Borschardt, Heinrich Brugsch, Emile Brugsch (1842-1930), Adolf Erman, Hermann Grapow, Carl Richard Lepsius, Somers Clarke (1841-1926), Emile Armelineau (1850-1915), Jean Capart (1877-1947), Gaston Maspero (18461916), Edouard Naville (1844-1926), Victor Loret (1859-1946), Sir John Gardner Wilkinson, Sir Alan H. Gardiner, Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie (Seriation at Abydos),James Henry Breasted, Auguste Mariette, Amelia Edwards (18311892), Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge (1857-1934), George Andrew Reisner (1867-1942), Howard Carter (1874-1939), Jaroslav Cerny (1898-1970), Dorothy Louise Eady (1904-1981), and Walter B. Emery (1903-1971).

Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (17971875) went to Egypt in 1821 to study tombs in the Valley of the Kings, the site of Karnak, and the sacred Gebel Barkal in Nubia, a mountain that appears to be shaped like a uraeus (the cobra that fronts the Egyptian king’s crown). Wilkinson made contributions to Egyptian epigraphy by copying inscriptions and being the first to identify the names of the kings with whom they were associated.

Rosellini (1800-1843) and his brother Gaetano accompanied Champollion on an expedition to Egypt in 1828 and directed the Italian committee as head archaeologist, while Champollion directed the French committee; supported by Leopoldo II, grand duke of Tuscany, and Charles X, King of France, their field study was called the Franco-Tuscan Expedition. Naturalist Guiseppe Raddi, artists Alessandro Ricci, Alexandre Duchesne, Albert Bertin, draftsman Nestor L’Hote, and Pierre Lehoux were major contributors to the project. Champollion and Rosellini published the results of their expedition in Monuments de I’Egypte et Nubie. This visionary title clearly suggests that these scholars surmised that there was a significant relationship between Nubia and Egypt; however, its significance has been overshadowed until recent times. Today, we know that Nubia’s influence on Egypt was far greater than many Egyptologists had suspected. For example, Nubian pottery has been unearthed and dated at 8000 BCE, which provides evidence that sedentary life in Nubia predates the Badarian, when Egyptian civilization began to coalesce; a great deal of effort has been directed at creating a rigid separation between the two areas, or populations. Importantly, metals like gold were virtually nonexistent above the Second Cataract (cataracts are the whitewater regions of the Nile); therefore, it was mined at Buhen or other Nubian sites and carted off to Egypt by the ton. Thus, Egypt’s reliance on Nubian products was perpetual, from the emergence of dynastic Egypt around 3250 BCE until the invasion of the Persian Archaemenid Dynasty in 525 BCE.

Rosellini (1800-1843) and his brother Gaetano accompanied Champollion on an expedition to Egypt in 1828 and directed the Italian committee as head archaeologist, while Champollion directed the French committee; supported by Leopoldo II, grand duke of Tuscany, and Charles X, King of France, their field study was called the Franco-Tuscan Expedition. Naturalist Guiseppe Raddi, artists Alessandro Ricci, Alexandre Duchesne, Albert Bertin, draftsman Nestor L’Hote, and Pierre Lehoux were major contributors to the project. Champollion and Rosellini published the results of their expedition in Monuments de I’Egypte et Nubie. This visionary title clearly suggests that these scholars surmised that there was a significant relationship between Nubia and Egypt; however, its significance has been overshadowed until recent times. Today, we know that Nubia’s influence on Egypt was far greater than many Egyptologists had suspected. For example, Nubian pottery has been unearthed and dated at 8000 BCE, which provides evidence that sedentary life in Nubia predates the Badarian, when Egyptian civilization began to coalesce; a great deal of effort has been directed at creating a rigid separation between the two areas, or populations. Importantly, metals like gold were virtually nonexistent above the Second Cataract (cataracts are the whitewater regions of the Nile); therefore, it was mined at Buhen or other Nubian sites and carted off to Egypt by the ton. Thus, Egypt’s reliance on Nubian products was perpetual, from the emergence of dynastic Egypt around 3250 BCE until the invasion of the Persian Archaemenid Dynasty in 525 BCE.

Owen Jones (1809-1874), a British engineer and draftsman, traveled to Egypt in 1832, made substantial drawings of Karnak, and published Views on the Nile from Cairo to the Second Cataract in 1843. Samuel Birch (1813-1855) wrote the introduction to Jones’s elaborate volume, which contained engraver George Moore’s lithographs of his original drawings, accurately documenting the architectural details of the various structures that Jones had encountered during his expedition. After collaborating with Joseph Bonomi and Samuel Sharpe, Jones published A Description ofthe Egyptian Court in 1854. Scottish artist David Roberts (1796-1864) went to Egypt shortly after Jones’s expedition, in 1838. Roberts believed that Abu Simbel was the most impressive of all Egyptian temples, and his various paintings became the most popular of his time.

Lepsius (1810-1884) led an expedition to Egypt from Germany, commissioned by Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, in 1842. Lepsius was accompanied by artist Joseph Bonomi and architect James Wild, and he published Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopien, 12 vol. in 1859 (Egyptian and Ethiopian Monuments), which rivaled the work published by Fourier in scale. Emmanuel vicomte de Rougé (1811-1872) worked with Lepsius to formulate a method for interpreting new Egyptian discoveries in a consistent manner. De Rougé was also curator of the Egyptian section at the Louvre in Paris.

Brugsch (1827-1894) collaborated with Mariette (a cousin of Nestor L’Hôte) in the 1850s, and his major contribution to Egyptology is his work on the decipherment of the demotic script; Brugsch worked at the Berlin Museum as well, and he held a number of posts related to Egyptology, including Founder and Director of the Cairo School of Egyptology. Mariette (1821-1881), an archaeologist known for virtually destroying archaeological sites, went to Egypt in 1850 to look for ancient manuscripts; however, he excavated Saqqara and Memphis instead, working in Egypt and sending antiquities to the Louvre until 1854. After returning to Egypt in 1858, he remained in Egypt and established the Egyptian Museum, after convincing the Ottoman Viceroy of Egypt of its merit. Mariette unearthed the temple of Seti I, as well as other temples at Edfu and Dendera. His work exposed material that dated back to the Old Kingdom, extending the range of Egyptian history that scholars could analyze.

Amelia Edwards (1831-1892) was a successful journalist who went to Egypt in 1873 and became enthralled with what she saw. Edwards published A Thousand Miles Up the Nile in 1877 and in 1882, founded the Egypt Exploration Fund (now known as the Egypt Exploration Society) to rescue ancient Egyptian monuments from decay, neglect, and vandalism. A wealthy British surgeon, Sir Erasmus Wilson, supported Edwards’s efforts until her death, shortly after she completed an American speaking tour that consisted of 115 lectures, in 1889. Edwards strongly endorsed Sir Flinders Petrie in her bequest for the establishment of a chair of Egyptology at University College in London; it contained a proviso that “Flinders Petrie should be the first professor.” Petrie (1853-1942) is considered to be “the father of modern Egyptology” by some Egyptologists. In conjunction, the archaeological methods that he developed extended beyond the Egyptian sites and are used by many of today’s archaeologists. Petrie excavated Naqada, Tanis, Naucritis, Tell-al-Amarna, the pyramids of Senusret II and Amenemhat II, and the cemetery at Abydos, from 1895 to 1899 (see the Methods in Egyptology section that follows).

Erman (1854-1937) elucidated and emphasized what he believed to be significant connections between ancient Egyptian language, the Coptic language, and Semitic languages. Three of Erman’s publications are considered to be among the most important that have ever been written on Egyptology: Ägyptische Grammatik (Egyptian Grammar), Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache (Dictionary of the Egyptian Language), and Neuägyptische Grammatik (New Egyptian Grammar). Grapow (1885-1967) was a protégé of Erman, and his publications focused on ancient Egyptian medicine. Gardiner (1879-1963), a student of Erman, is well-known for his interpretation of the Narmer Palate and his seminal 1927 publication, Egyptian Grammar, which is considered required reading for Egyptologists today.

Breasted (1865-1935) published the five-volume Ancient Records ofEgypt in 1906, A History ofEgypt (1905), Development of Religion and Thoughtin Ancient Egypt (1912), and A History of the Early World (1916) before his 1919 expedition to Egypt, while he was a professor of Egyptology and Oriental History at the University of Chicago. With the financial support of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., Breasted established the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, in 1919.

A number of other archaeologists, artists, authors, and architects could certainly be included among these important figures in the history of Egyptology, and their contributions to the discipline’s development must be acknowledged. Many of the Egyptologists who are working today will undoubtedly become part of this illustrious historic record.

Methods in Egyptology

The systematic study of Ancient Egypt has provided a wealth of information; however, it is of a relatively recent vintage. The Edict of Milan, which was issued in AD 313 by the Roman Empire, established Christianity as the empire’s official religion. As a result of this decree, representations of Egyptians gods and deities were attacked as symbols of “devil worship,” and Egyptian artifacts were zealously destroyed by Christians.

By the time Napoleon’s scholars arrived in Egypt to conduct systematic studies, significant damage to Egypt’s artifacts had already taken place. Egyptologists were forced to assess what remained with the understanding that looters, vandals, zealots, and adventurers had gotten to the sites ahead of them. When Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie arrived in Egypt to excavate Abydos near the end of the 19th century, he was horrified by the methods and practices that he observed used by Mariette at Khafre’s temple, which is documented in Lorna Oakes and Lucia Gahlin’s Ancient Egypt.

Mariette excavated the Serapaeum at Memphis as well, where the sacred Apis bulls had been buried. Mariette’s methods included the use of dynamite, which inherently destroys aspects of an archaeological site that may have been of importance. By intentional contrast, Petrie invented seriation, a method used by archaeologists to determine the sequences of artifact development, change, and frequency (or lack of frequency) in the layers of a site’s strata. For example, artifacts found in the lower levels of the strata are considered to represent an earlier techno-complex or habitation period in relation to the upper levels of the strata; seriation is a relative-dating technique. Petrie first used seriation at Naqada, Hu, and Abadlya, and his method is now widely used by modern archaeologists; at the very least, in this way, Egyptology certainly contributed to the study of humans as a whole. B. G. Trigger, B. J. Kemp, D. O’Connor, and A. B. Lloyd described Petrie’s method in their groundbreaking Ancient Egypt: A Social History, which was first published in 1983.

Petrie cut 900 strips of cardboard, each measuring 7 inches long, with each representing a grave that he had excavated; on each strip, Petrie recorded the pottery types and amounts, as well as the other grave goods, which allowed him to compare the grave’s contents and develop a relative chronology. Petrie’s meticulous method represented a watershed event in both Egyptology and archaeology, and seriation has undoubtedly enhanced the effort to analyze, preserve, and curate countless antiquities. In conjunction with seriation, a variety of methods are now used by Egyptologists to locate archaeological sites, including aerial photography, electromagnetic acoustic sounding radar, resistivity measurement, and thermal infrared imagery to indentify geological anomalies that merit further investigation. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR, a method of DNA molecule duplication that yields more material for analysis) and CAT-scans are now used to study the genetic relationships, or the lack thereof, between the human remains that have been unearthed and the pathology of their diseases. Computer programs that allow users to create 3-D reconstructions of sites and that allow users to type hieroglyphs are widely used by researchers, epigraphers, and students of Egyptology today. Relative dating methods, like stratigraphic palynology, and absolute dating methods, including thermoluminescence (TL), Radiocarbon (C-14), and electron spin resonance (ESR), are among the methods that can now be used to date artifacts, faunal, or floral material that is associated with Egyptian archaeological sites. These investigative tools have definitely enhanced Egyptologists’ ability to study the world of the ancient Egyptians.

A new method that is available to Egyptologists yielded some compelling results in August 2004. Gilles Dormion and Jean Yves Verd’hurt reported that they had found an unknown corridor that leads to a burial chamber in the tomb of Khufu, by using ground-penetrating radar; if they are correct, they may have solved an age-old mystery as to where Khufu was actually buried. However, as of now, Dormion and Verd’hurt have not been given permission to excavate.

Major Sites of Study

Mariette’s discovery of the Serapaeum at Memphis, and Khafre’s temple at Giza were major sites of study in the 19th century. Abydos, the center of the Osiris cult, was found to be equally significant. The Abydos site continues to be one of the most important in Egyptology. Based on the archaeological excavations of Dr. Gunter Dreyer from the 1990s, it appears that during the Gerzean, pharonic Egypt and hieroglyphic writing began at Abydos, about 3200 BCE. With the discovery of the tomb of King Scorpion (Sekhen), Dreyer found many of the markedly Egyptian cultural practices that would become definitive, including the mastaba, the ivory sceptre, the symbol of Horus, and the bulbous crown that symbolized a ruler’s dominion over Upper Egypt.

In conjunction, Dr. John Coleman Darnell and Deborah Darnell discovered the Scorpion Tableau nearby at the Jebel Tjauti site, which appears to be the earliest known example of the “smiting of the king’s enemies” mural that later Egyptian kings would commission. Karnak and Thebes (Luxor) are among the most studied sites of Upper Egypt, in conjunction with the Valley of the Kings, Deir el Medina, Hierakonpolis (where many ancient kings claimed to have been born), and Naqada. Dr. Kent Weeks is now conducting the Theban Mapping Project that is focusing on KV5 where Ramses II built interconnected tombs for his sons, which probably numbered over 50. KV5 represents an architectural project from antiquity that is completely unique. Egyptian kings were buried in the Valley of the Kings from about 1500 BCE to 1000 BCE, and the number of tombs located there is somewhat staggering, to say the least. At least six kings from the Ramesside Period were also buried in the Valley of the Kings, along with Merenptah, Tawosert and Sethnakhte, Seti I and II, Tuthmosis I, III, and IV, Siptah, Horemheb, Yuya and Tuya, and of course, Tutankhamun. Deir el Bahri in Western Thebes, the site of both Mentuhotep II and Hatshepsut’s tombs, continues to be a major site of interest to Egyptologists as well; the location of Hatshepsut’s tomb, which was built nearly 500 years after Mentuhotep II’s, exemplifies the later pharaoh’s desire to identify with and surpass her predecessor.

Some of the major archaeological sites of Lower Egypt are the illustrious Giza Plateau, Bubastis, Sais, Heliopolis, and Tanis. In the delta region, natural preservation is more problematic; however, astonishing finds associated with the 21st Dynasty have been unearthed. The silver coffins that were made during the Tanite Dynasty and its successors are exceptionally impressive, although this period in Egypt (29th-23rd Dynasties) may have been relatively chaotic, in view of the archaeological and historical records.

The major archaeological site of Middle Egypt is Tell al-Amarna (Akhetaten in antiquity), a city that was purposely built in the desert, in iconoclastic fashion, by king Akhenaten for his worship of the Aten. This site may represent the first example of a monotheistic king and state; however, Akhenaten’s motive may have been twofold. By abandoning the pantheon of Egyptian gods and deities that were in place, Akhenaten may have wanted all power to reside in him.

Many discoveries have been made as a result of restudies of sites that were already known. In this way, Upper, Middle, and Lower Egyptian sites provide perpetual enrichment for Egyptologists. For example, the Abusir site was excavated by Ludwig Borschardt (1863-1938) from 1902 to 1908; however, it is now being worked again, and its remarkable complexes are providing today’s Egyptologists with more knowledge about the lives of Raneferef, Sahure, and other kings from the 5th Dynasty.

In conjunction, the modern-day boundaries of Egypt do not correspond with the boundaries of the Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom, or New Kingdom. Therefore, Egyptian influence was prevalent below the First Cataract to areas south of the Third Cataract, and the number of pyramids in Nubia (modern-day Sudan) actually exceeds the number of pyramids that were built within the boundaries of modern Egypt. After Tuthmosis I (ca. 1504-1492 BCE) invaded Nubia, Amenhophis III built a well-known temple at Soleb. Akhenaten built a temple at Sesibi, which marks the southernmost point of the New Kingdom’s conquest of the Kushites.

Major Discoveries and Areas for Research in Egyptology

The discovery of the Rosetta stone in 1799 was one of the most critical of all discoveries, because it allowed Egyptologists to communicate with the ancient Egyptians. Without the Rosetta stone, much of what Egyptologists believe would probably be dependent upon conjecture. Therefore, the decipherment of hieroglyphic writing has clarified a great deal about antiquity, and it represents a major benefit for all researchers.

Djoser’s pyramid, Egypt’s first stone building, which consists of a series of stacked mastabas; the pyramid of Khufu (Cheops) at Giza; the Red Pyramid at Dashur; and the Kushite pyramids discovered at el-Kurru represent merely a few of the major architectural achievements of this culture area. Karnak Temple, Abu Simbel, and other examples of monumental architecture demonstrate the undeniable brilliance of ancient Egyptian mathematicians, engineers, architects, and workmen.

Recent discoveries in the Valley of the Kings are no less than remarkable, because Egyptologists are learning so much more about a site that some archaeologists considered to be exhausted about a 100 years ago. In conjunction, the inadvertent discovery of the blue lotus’s similarity to Viagra, in 2001, has transformed Egyptologist’s interpretation of Egyptian paintings. The virtually ubiquitous use of the plant has medical, sensual, and cultural implications that are now being studied.

Interpretations of the Evidence and Recent Theories

New theories about the mysterious Egyptian have now emerged that merit further scrutiny. Dr. Bob Brier has been examining the circumstances of King Tutankhamun’s early demise and his physical remains. For Brier, foul play is evident, based on a cranial anomaly and the political climate of the time. Some forensic scientists are not convinced; however, the evidence continues to be examined critically, and this research may broaden our understanding of the 18th Dynasty’s machinations in significant ways.

In 2000, Robert Bauval hypothesized that the configuration of the pyramids at Giza was aimed at replicating the heavens on earth; each pyramid represented a star, and it was to be placed in alignment with the constellation now known as Orion. By superimposing a scale model of the Giza Plateau upon a photograph of the constellation Orion, a correspondence between the alignment structures and the stars can be observed. If Bauval is correct, this would explain why the Egyptians invested so much effort in building projects that would propel them into the afterlife, at least in part.

Egyptologists cannot say exactly how the pyramids were built, and theories abound as to how such a feat could have been accomplished without the use of modern equipment. Dr. Maureen Clemmons, a Professor of Aeronautics at the California Institute of Technology, surmised that the ancient Egyptians may have built their pyramids by using kites and wind power. Overcoming a number of technical obstacles and setbacks in her field tests in the Mojave Desert, and with the assistance of Morteza Gharib and Emilio Graff, the team was able to raise a concrete obelisk that weighed about 3.5 tons in less than 5 minutes, using sails, wood, rope, and pulleys that would have been available to the ancient Egyptians. If Clemmons is correct, this would appear to be one of the most cogent explanations for how so many tons of stone could have been moved in antiquity.

Are these theories mere conjecture, or will they eventually enhance our understanding of the ancient Egyptian, who scholars have been struggling for centuries to understand? There are Egyptologists who take differing positions on these, and other, theories; however, divergent theoretical orientations serve as the foundation for scientific inquiry, and they often lead to breakthroughs, as Thomas Kuhn suggested in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

Preserving the Evidence/Sites

The rescue of the temples at Abu Simbel represents one of the most remarkable efforts known to Egyptologists. Ramses II built the two temples in Nubia; however, the rising level of the Aswan Dam, which was built in the 1950s, was about to flood their location and submerge the monuments forever. Through the efforts of UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), about $36 million was raised from international sources in order to move the temples to higher ground, and the temples were salvaged between 1963 and 1970. Clearly, this was a visionary undertaking, since the massive stone temples had to be dismantled in sections for future reassembly.

Tourism is a major sector of modern Egypt’s economy; however, numerous measures have been enacted to limit the deleterious effects upon the visitation sites. Humidity within the structures is now monitored, and the number of people who are allowed in per day is regulated. The natural decay of structures, like the Amenhotep III temple at Thebes, has been a recurrent problem since ancient times. Traffic and pollution have both served to hasten the deterioration of the Sphinx and other ancient monuments. Thus, human activities continue to be a threat to the cherished artifacts of this unique civilization, and this has been recognized by Dr. Zahi Hawass, Chief Inspector of Antiquities for the Egyptian government. Hawass engaged in numerous restoration and preservation projects at Edfu, Kom Obo, and Luxor, in conjunction with building tourist installations that are located a safe distance away from the sites, the use of safe zoning that separates a site from a town, and open-air museums. Taken together, these measures will complement the preservation efforts of the archaeologists who have permits to work alongside Egypt’s vital tourist industry.

The Value of Egyptology to Anthropology

Egyptology offers exceptionally fertile areas of study for all four of anthropology’s subfields. Physical anthropologists have gleaned a wealth of information about human adaptation, disease pathology, mating, and medicinal practices from ancient Egyptian remains; as for archaeologists, Egypt has exerted a substantial influence on their field considering the impact of seriation, which is widely used, developed by Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie.

The vibrant cultural array of Ancient Egypt and Nubia, including their pantheons of gods, philosophies, mating systems, and geopolitical interaction spheres, continues to be of interest to cultural anthropologists, with no evidence of abatement. And for linguists, the discovery of a unique, unpointed (written without vowels) language with a full compliment of written symbols has proven to be irresistible, at least since medieval times.

An incalculable number of anthropologists have drawn inspiration from Ancient Egyptian civilization, and they will probably continue to do so, while preserving its legacy for future generations of scholars and enthusiasts alike.

References:

- Bongioanni, A., & Croce, M. S. (Eds.). (2001). The treasures of Ancient Egypt from the Cairo Museum. New York: Universe.

- Hawass, Z. (2004). Hidden treasures of Ancient Egypt. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society.

- Johnson, P. (1999). The civilization of Ancient Egypt. New York: HarperCollins.

- Oakes, L., & Gahlin, L. (Eds.). (2003). Ancient Egypt. New York: Barnes & Noble Books.

- Shaw, I. (2002). The Oxford history of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Siliotti, A. (1998). The discovery of Ancient Egypt. Edison, NJ: Chartwell Books.

- Trigger, B. G., Kemp, B. J., O’Connor, D., & Lloyd, A. B. (1983). Ancient Egypt: A social history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Watterson, B. (1998). Women in Ancient Egypt. Gloucestershire, UK: Sutton.

Like? Share it!