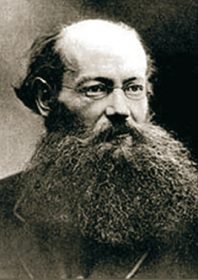

Peter (Pytor) Alekeyevich Kropotkin was a revolutionary and a philosopher; he was known for his works in other fields such as zoology, anthropology, and sociology. Kropotkin was the son of Prince Aleksey Petrovich Kropotkin of the old Russian aristocracy. He was educated in the elite Corps of the Pages, a special military school for boys of noble birth. From 1862 to 1867, Kropotkin served in the Army as an officer in Siberia; while there, he carried out original studies on cartography and geomorphology. Kropotkin proved that eastern Siberia was acted upon by post-Pliocene, continental glaciations. He found similar evidence in Finland and Sweden, thus theorizing that glaciers had once covered the northern plains of Eurasia and North America. A prolific writer, he developed his theories of libertarian communism on the principle of mutual aid, while observing tribal communities and the social life of the wild animals in Siberia.

As a result of his studies of animal life, Kropotkin theorized that mutual aid was the key to understanding human evolution. Most animals live in societies; Kropotkin believed that the survival strategy of safety was a concept needing closer examination, not just as a struggle for existence, but as protection from all natural conditions any species may face. Each individual increases its chances for survival by being a member of a group. Mutual protection allows certain individuals to attain old age and experience. With humans, collective groups allowed for the evolution of culture.

In the earliest band societies, social institutions were highly developed. In the later evolution of clans and tribes, these institutions were expanded to include larger groups. Chiefdoms and state societies carried this mutual identity to groups so large that an individual did not know all members. The idea of common defense of a territory and the shared character of nationalism appears in the growth of the group sharing a collective distinctiveness.

Kropotkin believed that science and morality needed to be united in the revolutionary project; education ought be global, humanistic, and empower everyone equally, and children should learn not only in the classroom, but also in nature and in living communities.

Mutual aid remains a necessary part of the life of any family, band, city, or nation. It becomes even more important for smaller groups in surviving the rule of an elite. Mutual aid becomes the foundation for our ethical systems; ethics is the basis of our biological evolution, and in this morality lies our collective material existence in nature. Kropotkin claims anarchism would extend mutual aid from family to include all of humanity. This idea of universal ethics is the origin of all universal religions and philosophies.

Kropotkin’s economic analysis began not with production, but with consumption established upon human needs. Needs are the starting point of production decisions; needs should not be determined by the greed and avarice of the individual. Economies should guarantee that all peoples’ needs are met with the least waste of energy. Hunger and want is the fault of an improper economic system, and not the fault of nature. Only an economy of mutual aid can meet all peoples’ needs; these needs include not only biological needs, but also all creative and emotional needs to live for the purpose of living the most meaningful life possible. Artistic creativity and concern for the well-being of oneself and others is the foundation for social morality, artistic creation, and the will to work at jobs that benefit the community.

According to Kropotkin’s theory, each community would produce as much of its local needs as possible, exchanging only what it can produce in surplus for what it cannot produce. Mutual aid and voluntary cooperation eliminate the need to motivate labor through greed, hunger, or coercion. Kropotkin stated that even those who do not work should be fed, as they are but the “ghosts of bourgeois society.” He felt strongly that most people would contribute to the well-being of others as long as they freely chose to do so.

Kropotkin believed that people easily can have all they need to be truly happy and healthy, and to live a meaningful life. In labor, work and art must be united. Through the rotation of jobs, all people share in both the noxious and creative work. Joy and responsibility cannot be separated. The separation of mental and physical labor can be eliminated. Decentralization can help reduce the poverty of separation of humans from nature.

Kropotkin believed that people easily can have all they need to be truly happy and healthy, and to live a meaningful life. In labor, work and art must be united. Through the rotation of jobs, all people share in both the noxious and creative work. Joy and responsibility cannot be separated. The separation of mental and physical labor can be eliminated. Decentralization can help reduce the poverty of separation of humans from nature.

Kropotkin believed it is possible for people to create a society in which unbridled wealth as well as all poverty can be eliminated. With wages or property, people could live in luxury with every need being met. This society can be achieved, Kropotkin wrote, only through propaganda of the deed, and through direct action. This unites a collective insurrection with a collective construction of society.

A large portion of contemporary social and biological science follows in the footsteps of Kropotkin’s academic work. Responding to the social Darwinism of his day, he wrote his primary scientific work, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, arguing that a major factor in the evolutionary success of humans was a predisposition to cooperate and share without the need for institutions such as the market or the state.

Research in anthropology has provided substantial confirmation to supporting mutual aid in non-market economies. Karl Polanyi, among others, has shown that a moral economy can and does exist. Anthropologists continually show extensive decentralized cooperation based upon reciprocity and redistribution. Marshal Sahlins writes that, in many cultures, selfishness is not rewarded. Substantivist economists have shown that people often give away substantial amounts of wealth. In many cultures, people actively cooperate against their own narrow self-interest. This is not simply “enlightened self-interest,” it is a genuine need for justice as it own justification. Biologists have acknowledged that competition among early human groups could have contributed to the evolution of cooperative behavior on the part of individuals. Both cooperation and competition has existed in the past.

In 1871, Kropotkin dedicated his life to social anarchism, mostly because of his observations of animal and human communities in Siberia during his military service. In 1874 he was imprisoned in Russia for his radical actions and beliefs. In 1876 he escaped and went into exile, fleeing first to Switzerland, then France, and finally settling in Britain in 1886. He supported the allies during World War I; because of this, he lost much of the respect he had held from his fellow anarchists. Because of the Russian Revolution, Kropotkin was allowed to return to Russia in June, 1917. Although Kropotkin was respected by both the Bolsheviks and the opposing forces, he was critical of both sides. After the Bolshevik Revolution succeeded in overthrowing the Revolutionary Provisional Government of Kerensky, Kropotkin strongly argued that a vanguard couldn’t make a revolution; only the people can fight a revolution and establish freedom. The Bolsheviks did not listen; brokenhearted, Kropotkin died in his beloved Russia in 1921.

For anthropologists, Kropotkin’s work on mutual aid is perhaps his most important contribution, not only in terms of his argument for the moral basis for communist anarchism, but also as the base for his theories of human evolution.

References:

- Carter, A. (2000). Analytical anarchism: Some conceptual foundations. Political Theory, 28(2), 230-253.

- Kropotkin, P. (1967). Memoirs of a revolutionist. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith.

- Kropotkin, P. (1967). Mutual aid. Boston: Extending Horizons.

- Kropotkin, P. (1970) Revolutionary pamphlets. New York: Dover.

- Kropotkin, P. (1989). The conquest of bread. Montreal, Canada: Black Rose.

- Woodcock, G. (1971). Anarchism: A history of Libertarian ideas and movements. New York: Meridian.

- Woodcock, G. (1971). The anarchist prince: Peter Kropotkin. New York: Schocken.

Like? Share it!