The words “magic” and “magical” are used in many different ways to refer to a huge variety of supernatural or wondrous phenomena, and even within anthropology there is inconsistency. So varied have been referents of the terms that some scholars have insisted that they have no cross-cultural validity and have urged that they not be used at all. But the word magic is firmly rooted in our language; it has been important in the development of anthropological theory, and ethnology has enabled the description of a set of features of magic that reveal important capacities of human cognition and cultural conceptualization.

When the word magic is encountered, the student should take care to ascertain just what it means. Some of the most common meanings of magic and magical include illusion or sleight-of-hand performed for entertainment; the ability to change something’s form, visibility, or location or to create something from nothing; spirit invocation and command; and having romantic, awe-inspiring, or wondrous qualities. During late medieval and Renaissance times, magical practices involving complex calculations and/or written notations and formulas based in esoteric knowledge were designated as high or hermetic magic to distinguish them from the “low” or simple magic of the uneducated peasantry. Any of the many meanings of sorcery or witchcraft may be labeled magic; indeed, these three terms are often used interchangeably. Sometimes modifiers, such as “black” (or white) magic and “demonic” magic, are used. During the 19th and early 20th centuries in Europe and America, a number of organizations devoted to “occult” practices developed. Some of these, such as the Ordo Templi Orientalis (Order of the Eastern Temple) and Order of the Golden Dawn, still exist today and designate their specialized ritual practices by the spelling magick. During modern times, the terms may designate anything psychic, paranormal, occult, or “New Age” or may designate any of the beliefs and practices of neopagan organizations such as Wicca, whose practitioners also prefer the spelling magick or, indeed, any reference to supernatural power or anything seeming miraculous or wondrous. The best anthropological meanings of the terms are quite different from any of the preceding meanings, but it has taken well over a century to arrive at them.

Magic in the History of Anthropology

Influenced by earlier positivism and contemporary evolutionism, scholars of the late 19th and early 20th centuries were interested in magic mainly as it related to religion and science. E. B. Tylor, in his Primitive Culture (1871), recognized that magic is based in principles of association, “a faculty which lies at the very foundation of human reason,” but he gave it no serious cognitive significance because the assumption of causal connections among associated things, although examples of it survived into modern times, is so clearly false that it represented a primitive stage in human thinking. James George Frazer built on Tylor’s writings and set down his lasting theory of sympathetic magic in the third edition of his monumental work, The Golden Bough (1911-1915). Frazer insisted on the evolutionary progression from magic through religion to science, and he maintained that the roles of magician and priest are separate and opposed, although he acknowledged that the principles of magic might combine with those of religion.

Marcel Mauss and his colleague Henri Hubert, in A General Theory of Magic (1902-1903), recognized the practice of magic as individual and private but emphasized its social implications. They focused on the Melanesian and Polynesian concept of mana as exemplifying the mystical power at the core of magical beliefs. The discussion of magic by Mauss’s uncle Émile Durkheim, in his The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1912 in French, 1915 in English), emphasized its distinction from religion; magic is derived from religion, but it is individualistic and hence has no role in social solidarity and no place in his theory of religion.

The Melanesian investigations of the great British social anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski produced two works about magic that were influential within and beyond anthropology: his great essay “Magic, Science, and Religion” (1925) and the two-volume Coral Gardens and Their Magic (1935). In his functionalist theory of culture, Malinowski emphasized that magic is neither primitive science nor a confusion of thinking but rather is a quite logical complement to practical knowledge and technique, integral with and routine in mundane activities. Malinowski paid special attention to the magic act, which has three components: the formula, the rite, and the condition of the performer. He also elaborated at length on the nature and importance of magical speech.

E. Evans-Pritchard was a student of Malinowski, and he also presented magic as a rational system of thought, but his great work Witchcraft, Oracles, and Magic Among the Azande (1937) stimulated anthropological investigations of witchcraft. With a few exceptions, social science discussion of magic over the subsequent six decades broke little new ground, presuming its uniqueness as a cognitive category separate from religion, and doubted its utility as a cross-cultural category. In his famous Frazer Lecture on taboo in 1939, Alfred R. Radcliffe-Brown advocated avoidance of the term magic until there was uniform agreement about its meaning. The French structuralist Claude Lévi-Strauss, in his introduction to a collection of Mauss’s major works in 1950 (English translation 1987), agreed that the universality of a mana-like concept represents “a permanent and universal form of thought,” but he criticized Mauss for having reduced “all magic” to mana, which is in fact a specific cultural concept and which differs greatly among various Melanesian and Polynesian cultures. And in his foreword to the 1972 English translation of Mauss’s General Theory, David Pocock said that “the importance” of the appearance of Mauss’s work at that time, with Lévi-Strauss’s commentary about it, “is that it contributes to the dissolution of ‘magic’ as a category.”

Alice and Irvin Child observed in their Religion and Magic in the Life of Traditional Peoples (1993) that “Frazer’s study of primitive magic was getting at fundamentals of human thought,” but throughout the 20th century most discussions of magic were premised on assumptions of its falsity and cognitive infancy; it was dealt with as of a totally separate order from religious phenomena, and scholarly concerns with various aspects of its mode and expression precluded investigations of its underlying cultural meanings or cognitive significance. Rosalie and Murray Wax provided an overview in their 1963 essay, “The Notion of Magic.” A comprehensive general social science survey, using “magic” to cover a wide range of techniques of supernatural manipulation, was Daniel O’Keefe’s Stolen Lightning: The Social Theory of Magic (1983). Stanley J. Tambiah’s Magic, Science, Religion, and the Scope of Rationality (1990) contained insightful assessments of major anthropological studies of magic.

Magic in World Ethnology

Michael F. Brown, in his comprehensive ethnography of magic among the Aguaruna of northern Peru, Tsewas Gift (1986), showed that for these people magic is not distinguished conceptually from religious or instrumental activity, and he seemed to echo Evans-Pritchard’s discussions of 50 years earlier: “nor is its logic independent of prevailing notions of material causality.” Brown urged more careful examination of the underlying symbolism of magical thinking and recognition of the full integration of magic in cultural conceptualization and expression. Anthropology today has the data, methodology, and philosophy to study magic as a basic mode of human thinking.

Ethnology, the cross-cultural comparative method of anthropology, has revealed certain principles that underlie magical thinking and are absolutely universal and for which there is evidence throughout recorded history and even in prehistory. The fact of their universality, strengthened by some recent discoveries in the brain sciences, suggests that we are dealing with fundamental structures of human cognition. Magic is best understood as beliefs and behavior involving at least some of six basic principles: power, natural forces, symbols, cosmic interconnections, and Frazer’s two principles of sympathetic magic (similarity and contact).

Power

Power is the universal idea that Mauss recognized, although it has specific variations and no single cultural concept, such as mana, should be used to generalize. People everywhere believe in a mystical communicable vital force that exists to varying degrees in all nature. Inanimate things have less power than animate things, lower order animals have less power than higher order beings, power increases in intensity up social and supernatural hierarchies, and contact by lower order beings with higher order power is dangerous. The biblical concept of God’s “glory” is an example. In people, power is carried in the blood and the breath and is energized by thought and intent. It is concentrated in the reproductive organs, and it is embodied in words and semen and menstrual blood and breast milk. Negative, especially dangerous forms of it are emitted through the excretory orifices and bodily lesions.

Natural Forces

All people also seem to believe that all nature is activated by forces that can be conceptualized as the engines of nature. They are energized by their own power and are programmed to do specific things, either singly or in concert with others. The forces can be manipulated by spirits, either of their own accord or after supplication by people through prayer and ritual, and they can be affected directly by people through magic without spiritual assistance.

Ethnology also reveals that the invocation and command of spirits is a universal feature of religion but that it ought to be reconsidered as a feature of magic. Probably all religions regard at least most of their spirits as sentient, willful, and potentially capricious, and all recognize serious risks in attempting to contact spirits directly and especially to command them. Conceptually, there is a great difference between the invocation of and effort to persuade presumably sentient and willful spiritual beings and the effort to exert direct control over presumably nonsentient forces of nature. Frazer, influenced by Tylor’s theory of animism, did recognize this problem, and he tried to get around it by arguing that when magic addresses spirits it treats them as “inanimistic agents” that submit passively to the magician. This lame assumption is unjustified in world ethnology and is surely one of the weakest points in Frazer’s generally insightful theory of magic. Even though apparently magical techniques may be involved, spirit invocation and command should be regarded as a distinct phenomenon of religious behavior and not categorized as magic.

In many systems, forces and power mighty not appear separate but may seem to merge, as in mana, Chinese qi, Greek dynamis, and the various concepts of flowing energies in traditional and New Age belief systems.

Symbols

Symbols are central to magic. Symbols are forms of representation that not only stand for other things but also can conceptually take on qualities of those other things so that they stand in for or take the place of those other things. If the thing the symbol represents has power, the symbol will become powerful. Words are symbols; so too are thoughts. Representations of religious beings and concepts and reproductive organs are especially powerful symbols. The power of symbols, containing the essence of the thing or act symbolized, can be projected through magic.

Cosmic Interconnections

People everywhere believe that all things in nature— past, present, and future—are mystically interconnected, either actually or potentially. And it is widely believed that everything that has happened, is happening somewhere else, or will happen is cosmically programmed and detectable. Magic can project influence through these connections.

Frazer’s Principles of Similarity and Contact

In his discussion of sympathetic magic, Frazer provided the best explanations for how the magical symbol is believed to work. Influenced by theories of positivism and natural law, he said that sympathetic magic operates according to the “law of sympathy,” which has two subtypes: the “law of similarity,” which states that things or actions that resemble others have a causal connection, and the “law of contact,” which states that things or actions that have been in contact with others, either spatially or temporally, retain a connection after they are separated. Mystical connections based in these principles, which Frazer called “homeopathic” and “contagious,” had been described since classical times, and Samuel Hahnemann had set down his principles of homeopathic medicine more than a century earlier. But Frazer elaborated on them at length and provided numerous ethnographic illustrations. Frazer made it clear that people understand the principles of similarity and contact to be operative in nature. A water-worn stone shaped like a particular fruit might be placed under a fruit tree to prompt its production. A tree or rock formation shaped like a phallus can be a source of power. Or, as recorded by Clifford Geertz, people of the tiny island of Bali feel confident next to the far bigger island of Java because their island is shaped like a fighting cock, whereas the Javanese live on a shapeless mass and so they are weak and aimless.

Other Ritual Practices

These principles of magic and magical thinking can be seen to operate in most manifestations of a number of ritual acts and concepts: good magic, sorcery, blessing and curse, taboo and pollution, divination, and magical protection.

Good Magic

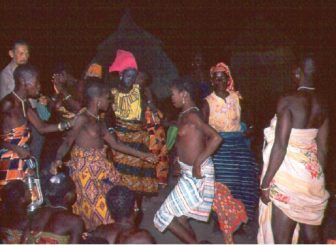

The natural order of things is good. Open, public good magic helps the forces of nature along their predetermined paths. People everywhere perform magical acts, speak persuasive words, and wear “lucky” items to increase the efficiency of the natural forces. Magic may be routine in certain economic endeavors (as Malinowski described for Trobriand gardeners and seagoing fishermen), farmers in Africa and South America employ rain charms, Aka net hunters of Central Africa sing hunting songs over their nets before the hunt or rub parts of captured animals on nets that have not caught anything for some time, and people universally employ magic in love and gambling. Magical control over game animals is a logical explanation for much of the cave art of the Upper Paleolithic, and the so-called “Venus figurines,” with exaggerated female reproductive and nurturance features, may well have been personal charms or amulets. On days when they will compete, athletes routinely wear items of clothing that they wore on days when they excelled at their sport, hoping to recreate at east part of the propitious set of cosmic interconnections that were operating on those days. In all cultures, names are intimately connected with their referents; by naming a thing, the individual exerts some control over it.

Sorcery

Sorcery is a loaded term with a great range of meanings having to do with individual manipulation of the supernatural for selfish or directly harmful ends. Referents of sorcery include invocation and command of spirits, but a generally accepted anthropological meaning of sorcery is magic. The sorcerer employs any of the methods of magic on his or her own behalf or on behalf of the client. Sorcery is clandestine, dangerous, and universally forbidden by society for three reasons. First, it operates directly counter to the natural program by directing the forces to alter their nature or direction, and havoc can result. Second, because the amount of goodness in the world may be considered to be finite, by seeking to obtain extra wealth or advantage for oneself, sorcery automatically deprives others. Third, if sorcery aims at direct harm to another, it is a criminal act.

The best-known example of sorcery is negative image magic, as in the unfortunately termed voodoo doll where harm is done to the image of a victim. Some instances of sorcery are quite complex and can be understood only through specifics of the language and culture of the practitioner, but some of the principles of magic can be detected in all. The simplest form of sorcery is a curse, that is, a direct verbal expression of ill will or a similar sentiment conveyed through a gesture.

Blessing and Curse

Blessing and curse are forms of verbal expression that must be distinguished from spirit invocation, which is a totally different phenomenon. “God bless you” asks God to do the blessing and is invocation, whereas “blessings on you” and “have a good day” are blessings or direct expressions of good will. The invocation “God damn you” asks God to condemn the target to eternal punishment in Hell, whereas “go to Hell!” is a curse because it conveys the same meaning but depends solely on the speaker’s intent and personal power and on the ability of the words to convey their meaning. Belief in the magical power of words is absolutely universal and is the basis for laws against slander and libel.

Taboo and Pollution

Taboo derives from a Melanesian and Polynesian concept most commonly meaning dangerous due to extraordinary mana. Popularly, it means forbidden by various sanctions. Magically, it means the avoidance of establishing a mystical connection by any of the principles of magic. Pollution means the conceptual “dirt” or malfunction that can result from the intermixing of powers that should remain separate, a possible result of taboo violation. Examples of both are numerous. Pregnant women should not carry pots due to the sympathetic connection to their swollen bellies, nor should they engage in acts of cutting, piercing, tying, tightening, or closing. Wives of harpoon hunters should not cut their hair while their husbands are hunting due to the symbolic connection to the strands of the harpoon ropes. The “uncleanliness” resultant from violation of any of the Jewish kosher laws, or from contact with a Dalit (a member of India’s “untouchable” caste), is pollution. Direct intrusion of the profane into the sacred, a concern of all religions, results in pollution. Pollution can cause failure, disorder, sickness, and death.

Superstition is a term that anthropologists should avoid because it indicates superiority of the user’s knowledge; but it is clear that many popular superstitions involve avoidance of magical acts. Examples include breaking a mirror, which can damage objects reflected in it; opening an umbrella, which is an object associated with storms, in the house, which is a place of calm and order; and stepping on a crack, which is damage. Any association with the number 13, which is the number of people at table in the Christian story of the Last Supper of Jesus, might bring about some calamity. Malinowski noted that people involved in risky or competitive enterprises routinely employ magic, including a range of taboos. In his classic article on baseball magic, George Gmelch described a player who ate pancakes for breakfast on a day he played poorly and who thereafter avoided pancakes on days he was to compete.

Divination

To discover “occult” information, one can ask spiritual agencies, and they may answer in a variety of ways. This is another example of spirit invocation. Magically, divination involves using any of the principles of magic to tap directly into the cosmic program in which there are traces of everything past, present, and future. “Reading” tea leaves, palms, the entrails of animals, or “omens” in nature is based in the assumption of cosmic interconnections. Hidden information can be elicited by the power of words, which carry their meaning into the cosmos and release the desired answers.

Magical Protection

It is universally believed that power can be abducted from any source, reformulated, and used for new purposes. Thus, the power of religious objects can repel evil that threatens a person, the contents of buildings, or activities in ritual spaces. Many such objects are cultural, but individuals can impart special powers to particular objects and behaviors. In many cases, protective magic resembles active magic, and specific cultural investigation into the intent of the maker or user may be necessary to distinguish a charm, which generally means an object that activates and directs magical power, from an amulet, which is an object that protects with a passive layer of power. For example, a rabbit’s foot, an appendage of an animal widely associated with nimbleness, speed, and reproductive power, can be either a charm or an amulet.

Explanations and Future Research

It seems clear that assumptions of causality according to the principles described in this entry are timeless and universal. Magic is evident in all areas of human endeavor and at all levels of society. The principles of magic explain why the baseball that was hit by Barry Bonds for his 700th career home run, or the baseball that was used to make the last out to win the World

Series for the Boston Red Sox in 2004, is instantly so valuable (the former sold at auction in 2004 for $804,000); why clothes or domestic items that once belonged to celebrities fetch such high prices at auction; why the pen that a president used to sign an important bill into law becomes a collector’s item; or why the residents of an eastern American town fight to save a 350-year-old oak tree that was “witness to so much history.” Magical symbolism accompanies and enhances religious ritual. Manufacturers of pills and furnishings know that colors are popularly associated with particular actions or effects. People become accustomed to daily routines and feel disoriented and incomplete if those routines are altered. A person applies “body English” to bowling balls or billiard balls, and a passenger in a car approaching a stationary object presses his or her right foot to the floor. Examples are endless.

Social science explanations for how magic “works” are various; in healing, either the natural progression of the disease or the placebo effect is most common. Apparent failures are blamed by practitioners on various factors, but rarely on the logic of the magical practice itself. Magic has been explained in terms of its psychological functions of giving people confidence and a sense of control in a complicated and uncertain world.

Better ethnographic studies are clearly needed. In 1963, the Waxes stated that theoretical efforts had failed because writers on magic “had not truly understood how the persons in question conceived the world.” And Michael Brown’s assertion in 1986 that there is “a pressing need for fine-grained accounts of magic as it is understood and practiced in specific societies” is still valid today, and not just among traditional societies; old magical beliefs are emerging in urban market economies in developing Third World areas. The ancient and universal beliefs that certain parts of the body are loci of concentrated power have stimulated both real and imagined trades in human body parts, presumably supplied by ritual murders of immigrants, homeless people, and orphans.

But it is also clear that magical thinking is a regular, normal, and fundamental mode of cognition. It is not just New Age or neopagan enthusiasts who demonstrate magical behaviors today; everyone does. A variety of functional explanations have been given for the ubiquity of magic, but there is mounting evidence that some of the principles of magic may derive from innate instinctual tendencies. The psychologists Carol Nemeroff and Paul Rozin conducted a series of studies during the 1980s and early 1990s indicating that ideas of contagion, the transfer of positive or negative influences by contact, are common and apparently natural. The recognition of universals in culture has long prompted anthropologists to suggest inherent biological bases for them, and today the new frontier in the understanding of magic may be the brain sciences. Symboling is at the basis of magic, and the capacity for imitation is at the basis of symboling. Neurobiological bases for the well-known imitation capability among primates were discovered during the 1990s, and recent studies by Marco Iacoboni and his colleagues at the University of California, Los Angeles, have indicated that there are bases for imitation in the cerebral cortex of the human brain.

References:

- Brown, M. F. (1986). Tsewa’s gift: Magic and meaning in an Amazonian society. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1937). Witchcraft, oracles, and magic among the Azande. Oxford, UK: Clarendon.

- Frazer, J. G. (1911). The Golden Bough: A study in magic and religion (3rd ed., 12 vols.). New York: Macmillan.

- Gmelch, G. (1989). Baseball magic. In A. C. Lehmann & J. E. Myers (Eds.), Magic, witchcraft, and religion: An anthropological study of the supernatural (2nd ed., pp. 295-301). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield.

- Malinowski, B. (1935). Coral gardens and their magic (2 vols.). London: Allen & Unwin.

- Malinowski, B. (1948). Magic, science, and religion and other essays. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Mauss, M. (1972). A general theory of magic (R. Brain, Trans.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Original work published 1902-1903)

- Meyer, B., & Pels, P. (Eds.). (2003). Magic and modernity: Interfaces of revelation and concealment. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Stevens, P., Jr. (1996). Magic. In D. Levinson & M. Ember (Eds.), Encyclopedia of cultural anthropology (pp. 721-726). New York: Henry Holt.

- Tambiah, S. J. (1990). Magic, science, religion, and the scope of rationality. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Like? Share it!