The German thinker Friedrich Nietzsche presented scathing criticisms of the human sociocultural world (particularly religion and theology) and called for a rigorous reevaluation of all values. Like Darwin, Nietzsche presented a dynamic view of reality. The philosopher had been greatly influenced by the evolutionary movement of the 19th century (although the intellectual relationship between Darwin and Nietzsche is not often emphasized or recognized).

Nietzsche is often referred to as the bold father of atheistic existentialism, a severe critic of science and reason, and even an early postmodernist. But if one comprehensively examines his worldview, it then becomes apparent that Nietzsche was also a philosopher of evolution (although he disagreed with Darwin’s interpretation of biological history). And despite his perspectivism, Nietzsche never rejected science and reason outright; surely he thought that some theories are closer to the truth than others, and for him evolution was a fact on all levels of reality. He also looked at the human condition from a cross-cultural perspective, thereby anticipating the ongoing anthropological framework that emerged in the 20th century.

Early Evolutionists

Darwin was troubled by the issues that were raised by his theory of evolution, particularly questions concerning the place of emerging humankind in planetary history. Evolution challenged the alleged uniqueness of our species, and it drew more attention to the existence of evil in the world. Furthermore, Darwinism did not support order or design or teleology in organic evolution. Darwin’s early interest in natural theology had been replaced by natural science.

Actually, Darwin himself never defended his theory in public, and he rarely answered his critics in print. Fortunately, two famous naturalists were eager to defend Darwinian evolution: Thomas Huxley in England and Ernst Haeckel in Germany. To further support scientific evolution, Huxley contributed evidence from his studies in comparative morphology, while Haeckel offered evidence from his research in comparative embryology.

Unfortunately, the early evolutionists did not know the correct age of the earth or the true mechanisms of inheritance. Moreover, no fossil hominid evidence had yet been found outside of Europe to clearly demonstrate the evolution of our own species. But during the 20th century, significant advances in science and technology, as well as momentous discoveries in genetics and anthropology, would answer many of those perplexing questions raised by the early evolutionists.

Still, before the end of the 19th century there were a few philosophers who accepted the fact of evolution. One in particular did not hesitate to seriously consider both the ethical and cosmological aspects of evolutionism as he saw them. Enter Nietzsche.

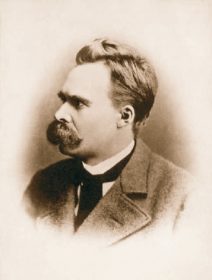

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche has emerged as the most influential philosopher of the last 100 years, although both controversy and confusion surround his life and thought. He was born on October 15, 1844 at Rocken in Saxony, Germany. His father, Karl Ludwig, a Lutheran pastor, died when Nietzsche was only five years old. Consequently, the precocious boy was raised in a household of females: his mother, sister, two aunts, and a grandmother.

The young Nietzsche enjoyed music and poetry. Later, his academic research shifted from theology through philology to philosophy. He developed an intense interest in classical Greek culture (especially the ideas of Heraclitus) and interpreted artistic expression as the synthesis of Apollonian individuality with Dionysian creativity.

Nietzsche read Charles Darwin and Arthur Schopenhauer, befriended Richard Wagner, and became a professor of classical philology at Basel University, Switzerland without completing a doctorate dissertation. After ten years, because of poor health and grave illness, he resigned his teaching position and, with a pension, became a solitary wanderer in the Alps of Italy and Switzerland. He remained isolated and lonely but authored remarkably prophetic and intellectually profound works of lasting significance.

With time to think and write, Nietzsche critically analyzed Western civilization and revealed the falsehoods and illusions that were pervasive within the conformity and mediocrity of modern society (as he saw it). He boldly proclaimed that “God is dead” and subsequently called for a rigorous reevaluation of all values. His penetrating genius not only distinguished between the “master morality” of creative individuals and the “slave morality” of the inept masses, but also contributed disquieting insights into the psychological motives of Christian beliefs and religious practices, for example, guilt, pity, and resentment.

With time to think and write, Nietzsche critically analyzed Western civilization and revealed the falsehoods and illusions that were pervasive within the conformity and mediocrity of modern society (as he saw it). He boldly proclaimed that “God is dead” and subsequently called for a rigorous reevaluation of all values. His penetrating genius not only distinguished between the “master morality” of creative individuals and the “slave morality” of the inept masses, but also contributed disquieting insights into the psychological motives of Christian beliefs and religious practices, for example, guilt, pity, and resentment.

Nietzsche was deeply concerned with what constitutes the “good life” for a human being and, as an existentialist, he stressed that self-fulfillment ought to be the goal of any creative and critical person who is challenged to overcome the pervasive conflicts in both the natural and social environments.

Nietzsche presented three remarkable ideas: the will to power, the future overman, and the eternal recurrence of the same.

Rejecting nihilism and pessimism, Nietzsche offered a radically new worldview that was optimistic and in step with the evolutionary movement of the 19th century. He held dynamic reality to be essentially the will to power and prophesied the coming of the overman (seeing the human species as a temporary link between the fossil apes of the past and those superior intellects that will emerge in the future).

In terms of metaphysics, Nietzsche taught his awesome and engaging concept of the eternal recurrence of the same as the endless and identical repetition of this finite and cyclical universe throughout all time. Essentially, the German philosopher emulated those pre-Socratic thinkers who had focused their attention on cosmological issues. Concerning ethics, Kant’s universalization of a free moral decision is transformed into Nietzsche’s eternalization of a seemingly free personal choice. As a result, Nietzsche claimed that each moment has infinite value and therefore one should live as if each decision is a choice made for eternity. In fact, he stressed that one should even love the pervasive necessity of determined reality.

Among his brilliant books, Nietzsche’s major work, Thus Spake Zarathustra (1883-1885), best represents his iconoclastic philosophy of perspectivism, overcoming, and fulfillment. With piercing insights, its author examined the human condition and found it to be oppressed by outmoded beliefs, narrow perspectives, and false values. His own emerging atheistic, this-worldly, and life-affirming vision challenges an individual to accept the endless flux of nature and to create new values beyond traditional conceptions of good and evil.

Scientific Evolution

The scientist Charles Darwin had awakened the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche from his dogmatic slumber by the realization that throughout organic history, no species is immutable (including humankind). Pervasive change replaced eternal fixity.

Darwin had embraced the facts, concepts, and perspectives in historical geology, comparative paleontology, and biogeography. For him, the “struggle for existence” in the living world always results in organic evolution by natural selection or the extinction of species due to their inadaptability. Although his scientific interpretation was mechanistic and materialistic, he himself did not get involved with the profound existential issues raised by this new worldview.

Darwin was not a philosopher. He did not concern himself with those questions that deal with the meaning and purpose of life on earth. Issues in ethics, metaphysics, and epistemology did not deter him in his rigorous investigations into the mechanisms of and evidences for organic evolution. No doubt, Darwin the scientist would have found Nietzsche’s philosophical speculations on life to be both incredible and inconsequential. But, if evolution is true, then what are the scientific implications, philosophical ramifications, and theological consequences for taking this brute fact of dynamic nature seriously?

Going beyond Darwin, Nietzsche offered a bold and provocative interpretation of dynamic nature that considered both the philosophical ramifications and theological consequences of taking the scientific fact of biological evolution seriously.

Clearly, Nietzsche was not oblivious to either geological time or the paleontological record. He accepted the most controversial implication of Darwin’s theory: humankind had evolved from remote apelike ancestors, in a completely naturalistic way, through a process of chance and necessity (fortuitous random variations appearing in, and inevitable natural selection acting on, individuals in a changing environment). Even the mental faculties of human beings, including love and reason, were acquired during the course of evolutionary ascent from earlier primate forms. Of course, this position rejected the traditional dualistic interpretation of our species as mind and body, and made clinging to a dogmatic ethical principle or a fixed set of values impossible. One is reminded of John Dewey’s interest in evolving values, although he could never accept Nietzsche’s focus on the value of an individual instead of the value of a community of inquirers.

For Nietzsche, evolution is the correct explanation for organic history, but it results in a disastrous picture of reality, since evolution (as he saw it) has far-reaching truths for both scientific cosmology and philosophical anthropology: God is no longer necessary to account for either the existence of this universe or the emergence of our human species from prehistoric animals. In fact, this philosopher held that Darwinian evolution led to a collapse of all traditional values, because both objective meaning and spiritual purpose for humankind had vanished from interpretations of reality (and consequently, there can be no fixed or certain morality).

Nietzsche knew that the previous philosophical systems from Plato and Aristotle to Kant and Hegel were inadequate to deal with the crisis of evolution. As a result, a totally new philosophy of the world was now required. So, Nietzsche offered an interpretation of reality that accepted the fluidity of nature, species, ideas, beliefs, and values. Furthermore, he held that it is nonsense to think that the fact of evolution can ever be taught as if it were a religion (since, for him, the process of evolution contains nothing that is stable or eternal or spiritual). Consequently, he would have rejected theistic evolution as an unsuccessful reconciliation of science with religion.

One can imagine Nietzsche’s tirades against the biblical fundamentalism and religious creationism that continue to threaten science and reason. An unabashed atheist, Nietzsche would have also abhorred Stephen J. Gould for upholding an unwarranted dualistic ontology that supports both the natural world of the scientist and the transcendent realm of the theologian. Instead, as a monist, Nietzsche would have admired Richard Dawkins and Daniel C. Dennett for their strictly naturalistic framework, which gives no credence to supernaturalism or spiritualism.

Nietzsche had assumed that the result of Darwinian evolution could only account for the success of inferior (weak and mediocre) forms of life simply in terms of sheer numbers, for example, the ubiquitous viruses, bacteria, insects, and fishes. The philosopher argued that Darwin’s blind species-struggle of the masses for existence needed to be replaced by his own discovery of the individual struggle by a few for self-creation and excellence.

Nietzsche saw the explanatory mechanism of natural selection as merely accounting for the quantity of species within organic history, but (for him) it is a vitalistic force that increases the quality of life forms throughout progressive biological evolution. He held that nature is essentially the will to power. Evolving life is not merely the Malthusian “struggle for existence,” but, more importantly, it is the ongoing striving toward ever-greater complexity, diversity, multiplicity, and creativity. In short, reminiscent of the interpretations offered by Lamarck, Henri Bergson, and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (among others), Nietzsche’s pervasive vitalism had substituted Darwin’s adaptive fitness with creative power.

The philosopher held that the evolution of organisms had its origin in primordial slime, but the human species now stands high and proud on top of the pyramid of life. Even so, he saw a natural tendency for the human animal to evolve toward common mediocrity. But, through the will to power, superior individuals have the potential to master their lives (overcoming nihilism, conformity, and pessimism), as well as the intellect to actualize creative activity.

Philosophical Anthropology

As with Thomas Huxley, Ernst Haeckel, and Darwin himself, Nietzsche taught the historical continuity between human beings and other animals (especially the chimpanzees). However, the philosopher as elitist did assert that some individuals will rise far above the beasts, including the human species, but this will only occur in the remote future with the emergence of the noble overman.

If humans have ascended from the fossil apes, then why should they not be followed by an even higher form of life (as the ape has been surpassed by the human animal of today)? According to Nietzsche, the human biological species is the meaning and purpose of the earth so far, because it is the arrow pointing from the past ape to the future overman. But what is an overman? This exalted but unimaginable being will be as intellectually advanced beyond the present human animal as our species of today is biologically advanced beyond the lowly worm.

For Nietzsche, the aesthetic evolutionist as sculptor, the coming overman is like an ideal image sleeping in a crude rock. In carving out this superior being, the philosopher was guided by its shadow, although he remained indifferent to the destruction resulting from his intense creativity: “Fragments fly from the stone; what is that to me?”

Unlike the silenced priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a geopaleontologist and Jesuit mystic, Nietzsche did not foresee a final end-goal or an ultimate omega point for human evolution. Instead, the finite becomes infinite. Nietzsche’s metaphysics is grounded in the colossal idea of an eternal recurrence of this same universe, that is, an infinite series of identical finite cosmic cycles. Although there is organic evolution on earth within each cycle, there is no progressive evolution from universe to universe.

Consequently, Nietzsche’s process cosmology represents being as becoming, and its teleological evolution from primordial slime to the future overman within each cycle is strictly determined. In the future, the noble and radiant overman will accept the eternal recurrence of the same, with its existential consequence being the affirmation of life as it was, is now, and always will be.

Reflecting on the immediate future, Nietzsche foresaw horrific wars due to conflicts of interests. Nevertheless, he himself was always optimistic that at least some gifted individuals would surmount the trials and tribulations of the human condition. The quintessential value of our advancing species (as he saw it) lies in its superior artists, philosophers, and scientists.

Nietzsche did not speculate on life or intelligence or evolution elsewhere in this universe. Furthermore, this philosopher could not have imagined mass extinctions, nanotechnology, genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, and human space travel to other planets. However, continuing advances in science and technology will offer incredible possibilities for neolife and overbeings in the ages ahead.

Nietzsche had taken time, change, and evolution seriously. He had naturalized metaphysics (ontology and cosmology), epistemology, and values. Furthermore, Nietzsche was acutely aware that this universe is totally indifferent to human existence. Yet, his philosophy presents an optimistic challenge for those individuals who are willing to follow the lightning bolts of his heroic vision.

Darwin’s influence on Nietzsche is obvious, although the two geniuses offered vastly different interpretations of evolution. Nietzsche saw human creativity as the extension of creative evolution within a creative universe. Taking this dynamic perspective to its logical conclusion, he saw our species as merely a temporary link between those past (lower) apelike forms and the future (higher) overman to come. For this philosopher, the “good life” of an individual is one that overcomes problems while it devotes itself to creativity.

In Turin on January 3, 1889, while attempting to protect a horse from being beaten by its owner, Friedrich Nietzsche collapsed in the street. He was diagnosed clinically insane due to tertiary syphilis. During the next ten years, first under the care of his mother Franziska and then his sister Elisabeth, Nietzsche remained unaware of his growing reputation as a singularly influential thinker. His genius was now silent. After his death on August 25,1900, the teacher of eternal recurrence was buried in Röcken, the town of his birth.

In the decades and centuries to come, our understanding of and appreciation for both organic evolution and our own species will increase in light of new facts, new concepts, and new perspectives. No doubt, there will be surprising discoveries concerning the history of life and human nature. As such, science and philosophy will move far beyond both Darwin and Nietzsche, but certainly never without them.

References:

- Cate, C. (2005). Friedrich Nietzsche. New York: Overlook Press.

- Köhler, J. (2002). Zarathustras secret: The interior life of Friedrich Nietzsche. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Safranski, R. (2001). Nietzsche: A philosophical biography. New York: Norton.

- Welshon, R. (2004). The philosophy of Nietzsche. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Like? Share it!