Human actions are the fundamental phenomena that all theories of knowing, learning, and development aspire to explain. However, most theories do not explain concrete individual actions, but provide probabilistic estimates for central tendencies. Most theories also consider actions as expressions and causal consequences of underlying, hidden social or psychological phenomena. Activity theory, on the other hand, is concerned with understanding real, concrete activity in the very settings where it occurs, based on the grounds individual and collective human agents have for doing what they do. Activity theory therefore aspires to understand and explain each form of action in its concrete material detail, whatever the situation. Because of this orientation, the theory has been in favor with researchers interested in assisting companies and schools in redesigning and changing their everyday work environment. The theory presupposes that structural aspects of a setting mediate activity and that these structures can be understood only by considering their cultural and historical context. A more descriptive name frequently used for the theory is therefore cultural historical activity theory or CHAT. Social activities (e.g., fish hatching, teaching, researching), which have arisen as a result of the division of labor in society, are the basic units of analysis in CHAT. The nature of an activity such as fish hatching can never be understood by studying it in the abstract, that is, by analyzing the idea of fish hatching; it requires instead the study of the concrete material details of fish hatching as a synchronically and diachronically situated system.

Historical Origins

Cultural historical activity theory has arisen in response to idealism, which splits concrete human activity from abstract thinking. Grounding their work in the dialectical materialist approach of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Soviet psychologists such as Lev Vygotsky worked to establish a theory that could simultaneously account for knowledge as the result of concrete human actions and of sociocultural mediation; this is now known as first-generation activity theory. Other Soviet psychologists, including Alexander Luria and Alexei Leont’ev, further elaborated this position by including a dialectical relationship between the individual and collective (culture, society); this is now known as second-generation activity theory. Their work constituted the basis for more recent, Western European developments: the Finnish scholar Yrjö Engeström developed a structural perspective on activity systems, whereas the German critical psychologist Klaus Holzkamp worked out a theoretical and methodological framework that focuses on a subject-centered perspective of human activity. Third-generation activity theory is concerned with understanding and modeling networks of activity systems.

Power To Act, Agency

Fundamental to CHAT is the human ability to act or agency. Individual knowledge can be thought of in terms of the action possibilities (room to maneuver) individuals have in concrete situations; an increase in action possibilities constitutes learning and development. Culture and cultural knowledge can then be theorized as the generalized action possibilities, which exist at the collective level—any action, even the most atrocious war crimes, are then concrete realizations of possibilities for which the culture as a whole is responsible. Importantly, existing culture is reproduced and new culture produced in the concrete actions of individuals. These actions always arise from the (dialectic) relation of the social and material (i.e., sociomaterial) structures in concrete settings, on the one hand, and the internal, mental structures (schemas) that enable perception of these external structures, on the other.

Agency and structure are dialectically related; they presuppose one another. Structure exists both as social and material resources and as schemas. The resources and schemas are dialectically related: schemas develop as the newborn individual engages with the world, but the perception of the world requires schemas. New schemas are therefore coextensive with new life world elements available to the individual consciousness. Because of this dialectical relationship, individual development is both highly idiosyncratic, leading to differences in the schema developed, but also highly constrained, given that all individuals interact with the same material structures and cultural practices.

Agency also means that the human subjects of an activity system are not mere responders to fixed external conditions; they are endowed with the power to act and thereby change their conditions. Thus, to take a concrete example, fish culturists and hatchery managers are not merely cultural dopes reacting to external conditions or blindly following rules. Rather, hatchery workers actively contribute to reproducing fish hatching as concrete activity, and they produce fish hatching in new ways and therefore contribute to individual and collective learning and development. However, agency and therefore control over the context are not unlimited. Objectively experienced structures in the hatchery and higher organizational levels constrain what any hatchery employee can do. There are always social and material constraints on actions. Thus, the agency of hatchery employees is dialectical: both subjectively determining and objectively determined by their life conditions. CHAT articulates human learning and development in terms of the expanding control over the conditions.

Hierarchical Levels Within Activity

In CHAT, actions play a special role because this is what human individuals bring about and what researchers observe. In many situations, feeding fish, uttering a request for more fish feed, or (mentally) adding the number of feed bags to find the total amount of feed distributed in a day are typical actions because they realize conscious goals articulated by individual hatchery workers. An action implies both physical (bodily) involvement—even mental arithmetic requires a human body—and participation in social activity (fish hatching). Actions also imply acting subjects and objects acted on. Actions, however, do not constitute the smallest element in the analysis because they are realized by unconsciously produced elements, operations. To understand or theorize any moment of human activity, three concurrent levels of events need to be distinguished: activities, actions, and operations.

Activities, Actions, Operations

Activities are directed toward objects, always formulated and realized by collective entities (community, society). Fish hatching is an activity; fish culturists can earn a salary, which they use to satisfy their basic and other needs, because fish hatching contributes to the maintenance of society as a whole. Actions are directed toward goals, framed by subjects (individuals, groups); feeding fish constitutes an action because at any time during the day, fish culturists make conscious decisions (form the goal) to go to the ponds and throw food. Operations are unconscious, oriented toward the current conditions: for example, the current state of the action and its relation to the sociomaterial structures of the setting. Experienced fish culturists do not have to form the goal, “flick the hand to spread the food as widely as possible,” but their arms and hands produce the required movements, making adjustments to the amount of food currently on the scoop, wind, distribution of fish in the pond, or weight of the scoop.

It is apparent that in the course of individual and collective development, particular phenomena change levels. For example, at some time in the cultural historical evolution, human individuals who needed some tool decided to make it—even chimpanzees fashion branches to “fish” termites from their mounds. Later, as part of the division of labor, tool making became an activity in its own right. For example, one hatchery worker fashioned a mechanical feeder from scratch, including a leaf blower. If a company were formed to build such mechanical feeders in large numbers, a new activity system would have formed. A movement in the opposite direction is observed when newcomers to the hatchery learn to feed fish. Initially, the feed thrown with a scoop tends to clump, leading to feed falling to the bottom of the pond, both wasting feed and giving rise to dangerous bacterial growth. The newcomer consciously focuses on flicking the hand holding the scoop to spread the feed as widely as possible—here flicking the hand is an action. But with time, the newcomer no longer needs to consciously focus on flicking the hand, which now has become an operation contributing to realizing feeding fish.

Sense, Reference, Meaning

Activities and actions are dialectically related: actions concretely realize activities, one action at a time, but they are oriented toward the realization of an activity. That is, activities presuppose the actions that realize them, but actions presuppose the activities that they realize. It is in its relation to the activity that an action obtains its sense: the sense of feeding fish in a hatchery differs from feeding fish in a home aquarium or feeding fish at the Vancouver Aquarium Marine Science Center. Actions and operations also mutually constitute and therefore presuppose one another: operations concretely realize specific actions, thereby presupposing the former, but actions are the context in response to which operations emerge. Actions therefore constitute the referents in response to which operations emerge. The hatchery workers’ hand flick operations presuppose fish feeding, but fish feeding only exists in the material details of operations such as filling the scoop, extending the arm, and flicking the hand. It is only in the dual orientation of actions to activities (sense) and operations (reference) that we can talk of meaning. An action is grounded both in the body that produces it and in the culture that gives it its sense. Communicative actions (including sentences, words, and other symbols) are meaningful only in their simultaneous relation to collective activity and embodied operations (e.g., unconscious production of words and gestures).

Nature Of Human Activities

Subject and Object

Cultural historical activity theory presupposes human activity (e.g., fish hatching) as its basic unit of analysis. This unit is dialectical in the sense that however we partition it, each part can be understood only in its relation to all other parts. The most fundamental partition that can be made is that between the acting subject and object. For example, to understand the concrete activity of fish hatching, we can ask “Who is doing the work?” “What are they working on?” and “What is the result?” The answer to the first question gives us the subject, individual or group (hatchery personnel); the answer to the second question gives us the object, the raw materials involved in hatchery operations, eggs, milt, and the continuously developing young fish. The result to the third question gives us the outcomes of the activity, for example, “a well stocked river.” To understand fish hatching, subject and object cannot be understood independently of one another: fish culturists are defined by what they are working on as much as the things being worked on are defined by the fish culturists. Most importantly, activity theory conceives of subject and object as appearing twice: as concrete structures and schemas. To understand a concrete activity (or action), one needs to know how the raw materials appear to the acting subject and what its visions are for the future outcomes.

Motive, Emotion, Motivation

Motivation and emotion are tied to the motive of activity. They do not exist independently from cognition, impinging somehow from the outside. Rather, they are integral to its constitution. Fish culturists identifying with the hatchery, and therefore pursuing its central motive, are also highly motivated in their everyday work. They “go the extra mile.” Because of this identification, everything they learn contributes to the development of the hatchery community: every benefit to the collective becomes a learning opportunity for others. Their attunements to the hatchery and to themselves as participants become indistinguishable. Fish culturists who do not identify with the hatchery have as their object (motive) the earning of a salary. Their motive is therefore different, no longer coinciding with the production of fish. These individuals may be disgruntled, work to rule, and dissociate themselves from the collective motive.

Figure 1 The structure of an activity system, using a hatchery as a specific example.

Identity

In acting toward the object, subjects of activity not only produce outcomes but also reproduce themselves and their community. When hatchery workers feed fish, they reproduce the cultural practice of fish feeding; in the same action of fish feeding, however, they also constitute themselves as members of the hatchery. Identity—who the subject is with respect to others in the relevant community—emerges as the outcome of engagement with the object; that is, as the result of real concrete activity.

Structure And History Of Human Activities

Structure of Activity

To study a concrete activity such as fish hatching, researchers begin by articulating the activity and then ask what its constituent structures might be. One commonly used heuristic includes six basic conceptual entities (Figure 1): subject (individuals or groups), object (artifact, motive), means of production (including instruments, artifacts, and language), community, division of labor, and rules. Two points are important. First, none of these six entities can be studied in isolation because in a particular concrete activity, the subject (which schemas are brought to bear) and the relevant object (which material structures are currently relevant) presuppose one another. The scoop for throwing feed is used in ways characteristic of fish hatching practices, which is different from the ways in which scoops are used in other activities. Second, the diagram only presents the system at single point in time. But CHAT has a second focus in the cultural and historical nature of activity; that is, the diachronic aspect of human activity. This aspect is poorly represented in the commonly used heuristic. The activity system as a whole and each of its constitutive parts require an understanding of the cultural historical context.

Analyzing Activity

To understand any particular action observed, for example, fish feeding, requires an analysis of the tools that are used (scoop and bucket versus mechanical food spreader), the division of labor (permanently employed fish culturist versus temporary worker), and the nature of the object (different salmon require different amounts of food, different rates of weight increase, different target weights before release). To understand why one fish culturist uses hydrogen peroxide and another one plain salt as a disinfectant, or why one fish culturist uses a product called “MS-222” whereas another uses carbon dioxide as an anesthetic, researchers need to investigate the individual and collective development of these fish culturists and this hatchery. To understand why two fish culturists change the grain size of the feed that they distribute to fish at different moments in time, one needs to understand where they are with respect to their own professional and developmental trajectories (identities). One of them may have learned, for example, to perceive fish spitting out or nibbling feed of inappropriate hardness, size, or composition.

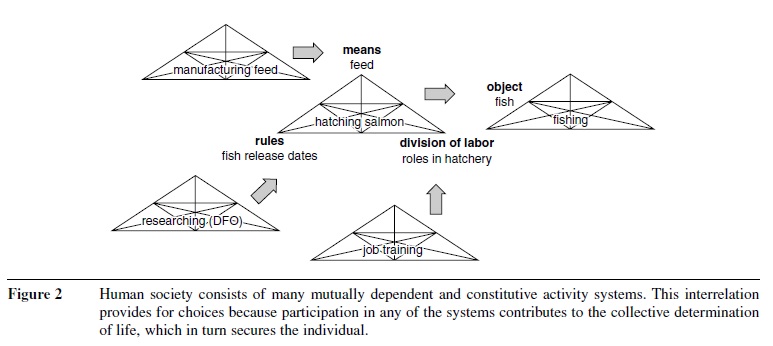

Figure 2 Human society consists of many mutually dependent and constitutive activity systems. This interrelation provides for choices because participation in any of the systems contributes to the collective determination of life, which in turn secures the individual.

Figure 2 Human society consists of many mutually dependent and constitutive activity systems. This interrelation provides for choices because participation in any of the systems contributes to the collective determination of life, which in turn secures the individual.

Historical Contingency

Whatever happens in the hatchery requires understanding the historical evolution of the hatchery and its larger cultural context, the Salmonid Enhancement Program of the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans. This department has itself undergone changes, such as increased and decreased levels of funding that have mediated the events in the hatchery, and thereby shaped any of its constituent parts, including individual learning and employees’ identities. To understand the relative freedom of individual fish culturists to make decisions in their ongoing work of raising fish and their noninvolvement in the decision about when fish are to be released requires careful historical and structural analyses of management– worker relationships and transitions in management over time.

Division of Labor: Society as a Network of Activities

In the same way that an activity cannot be understood apart from its historical context, it cannot be understood apart from its cultural (societal) context. Historically, different forms of activity have evolved through division of labor, which has allowed some people, at some point in history, to hunt or farm and others to produce hunting and farming tools. Through exchange (Figure 1), which in early history took place in the form of bartering, game, grains, and tools were exchanged, providing for the needs of all members of a society, who consume the fruits of their labor literally and metaphorically. Through such exchanges, economic, cultural, and symbolic capital comes to be distributed unevenly both within and between activity systems and between individual (worker, millionaire) and collective subjects (social classes). Today, society consists of complex networks of activity systems. Thus, a fish hatchery is connected to many other activity systems, independent of which the events inside the hatchery cannot be understood—a typical articulation of third-generation CHAT (Figure 2). An increased number of salmon in the local river, estuary, and nearby ocean provides the resources on which commercial fishery depend. It also provides resources for sports fishery, which creates a tourist industry, on which hotels, restaurants, or angling and other shops depend. The participants in the different activity systems can then exchange their earnings for food and shelter, the products of yet other activity systems. That is, participation in fish hatching secures hatchery workers with opportunities to fulfill their needs without having to fish, hunt, gather, or farm. That is, participation in fish hatching frees individual hatchery workers from depending on the conditions in an adverse world and allows them to control their own conditions by participating in the collective control of life conditions.

Contradictions

Contradictions are important to CHAT because they are starting points for thinking about and enacting change, which leads to learning and development. Contradictions can be identified within an element, between pairs of elements, between the objects of the system in its current and more advanced forms, and between neighboring systems. Identifying contradictions within activity systems and how they arise and function generally requires critical analysis. There are two forms of contradictions: inner contradictions are those that arise from the unit of activity as a whole, whereas differences, inconsistencies, antinomies, breakdowns, and logical (external) contradictions are expressions of deeper inner contradictions. External contradictions mediate (impede) with the activity, but fixing them is equivalent to treating symptoms rather than causes (inner contradictions). Two examples may illustrate the nature of these contradictions. First, verbal utterance “You have to flick your hand like this” and the gesticulations that accompany it express the same idea (unit); the difference between utterance and gesticulations is an external expression of an inner contradiction of communication in general. Because utterance and gesticulations are different, they may also express different things. Thus, during human development, words and corresponding gestures may express different ideas, or utterances may lag with respect to the corresponding gestures, giving rise to additional contradictions. Second, graphs used in the hatchery and their corresponding verbal descriptions by a fish culturist express the same ideas but do so in very different ways (material, form). The inner contradiction lies in the fact that each representation is an expression of something without actually being the something (idea).

In workplace and information technology design studies, the identification of contradictions has become an important tool for understanding activity systems, redesigning and changing them, or introducing new tools. All these actions contribute to change and development of and within the system. Contradictions therefore are opportunities for orienting change processes, a reason for the popularity of CHAT in praxis-oriented communities (design, teaching, counseling). But the presence of contradictions is not a sufficient condition for change. Thus, although there were evident contradictions between the fish culturists’ and their manager’s assessments of fish release dates, these were reproduced year after year without leading to any noticeable change in the decisionmaking practices. True inner contradictions, however, push the activity continuously ahead. Thus, in his classic study, Karl Marx showed how the inner contradiction of a commodity, externally expressed in the antinomy of use-and-exchange value, was the driving force that made a barter-based society evolve into a capitalist society.

Knowledge, Learning, And Development

Knowledge

In CHAT, knowledge cannot be talked about in the abstract. Knowledge does not exist as something out there or beyond the world of appearances. It is better thought of in terms of knowledgeability, always exhibited in the concrete details of practical action. Because of the commitment to activity as unit of analysis, the assessment of what hatchery workers know depends on the context. If hatchery workers are asked to do paper-and-pencil problems, for example, about graphs in general, they no longer participate in their normal everyday activity system but in the researcher’s, which focuses on the production of completed problem sheets. Because tools (paper and pencil), object of activity, community, rules, and division of labor differ, the kinds and levels of knowledgeability expressed in the respective actions also differ. If researchers study how the fish culturists use graphs to track the average weight of fish as part of their daily work, they will notice deep understanding and integration of graphs into the work processes. How well the fish culturists do on paper-and-pencil graphing tasks does not predict how well they use graphs at work—results that reflect those that have been observed among research scientists.

The distinction between what is inside and outside an individual’s head is no longer useful because actions inherently constitute the interface between inside and outside. Whenever a person does something, it happens both in the world, available to other participants in the activity, and inside, as neuronal event. It may be objected that “thinking,” such as mental arithmetic involved in adding 12 and 15 bags of feed, is internal. Vygotsky already pointed to the empirical fact that thinking is inner speech. The underlying processes that eventually allow the person to pronounce the result 27 bags of feed therefore require the same inner processes that previously have been associated with adding numbers aloud in the presence of an elementary school teacher.

Subjectivity and Intersubjectivity

Subjectivity and intersubjectivity are dialectically related. At the very moment that humans utter sentences, they presuppose that others already understand.

The same is true for actions. Humans always have grounds for their actions and attribute similar intentionality to the actions of others. When fish culturists on stand-by report that “5,000 fish died,” they presuppose the intelligibility to the recipient of the report. However, what one person knows (that 5,000 fish are dead or that the fish tank was overheating) may not be known to another. These differences arise from the material difference between the subjects and their subjectivities, each of which nevertheless concretely realizes generalized, cultural possibilities (intersubjectivity). That is, although the intelligibility of the news exists at the general level, the specific news (knowledge) is concretely realized in different material bodies, which are therefore forced to communicate to ascertain that they are aligned with respect to their understandings of the current state.

Expansive and Defensive Learning

An increase in individual or collective action possibilities constitutes learning. Increases in possibilities constitute greater control over situations and therefore are inherently motivating—this is expansive learning. There are many instances, however, when individuals learn not because it provides them with desirable increases in their room to maneuver but because they want to avoid punishment—this is defensive learning. For example, fish culturists might take an online course because the managers require it but for which they do not see much use. They would study for the exams only to forget what they studied a short time after. Here, the fear of getting low grades, which might affect not only their career but also future job prospects and other aspects of life, would encourage them to study and (reasonably) do well. They might study but lack inherent motivation.

Individual and Collective Development

Vygotsky introduced the (asymmetrical) notion of zone of proximal development to theorize activity and learning when less able individuals achieve at a higher level while working with more able individuals. The zone of proximal development is then the distance between unaided and aided actions. The notion is asymmetrical because it focuses on the learning of one individual rather than on co-theorizing the additional possibilities available to all individuals who participate in collective activity. In CHAT, centrally concerned with the relation between individual and collective, the zone of proximal development is understood as the distance between the everyday actions of individuals and the historically new and culturally more advanced actions within a collective.

In a fish hatchery, there are many jobs that individuals could do on their own, such as capturing a female salmon in a holding tank, killing it, and taking the eggs. However, two or three fish culturists working together are more efficient at doing the job, not just because there are two or three times as many hands for the same actions but also because working collectively, a whole range of new actions become possible. Thus, working alone, an individual would have to attempt to catch a fish with a dip net, a truly difficult task. Working collectively, one fish culturist can use a dip net as a barrier or can step into the holding tank (dressed in a wet suit) and use the body as an additional form of barrier, while the other is “chasing” the fish in the manner a fish culturist would do working alone. Neither action is observed when there is only one person. An expansion of action possibilities constitutes development of the entire activity system. That is, approaching tasks collectively results in situations that provide new action possibilities exceeding the sum of individual possibilities. Because the action possibilities have expanded, there are now new possibilities for individual learning, because in the concrete realization of some new action, the individual subject acquires new competencies and thereby expands collective possibilities. To continue with the previous example, fish culturists can now learn how to use their bodies together with dip nets for crowding fish, something they cannot learn when working on their own. That is, because individual and collective stand in a dialectical relationship, individual and collective developments are linked. Each action produces resources that change the totality of resources available to the individual and the collective. New resources mean new possibilities to act and therefore are coextensive with development of the collective.

Summary

Cultural historical activity theory is concerned with understanding and explaining real, everyday, situated activity in its concrete, material detail. Its purpose is to provide accounts for the particulars of each action rather than probabilistic description that may not be applicable to any single action or activity. It achieves this purpose by including all relevant and salient detail. CHAT arrives at a comprehensive picture of human culture by constructing a tight link between individual and collective. However, CHAT is not a master theory, a theory of everything, because it understands itself as the outcome of an activity system: at any moment it is the current provisional and contingent product of a continuously evolving historical process of theorizing practical activity.

References:

- Bedny, Z., & Karwowski, W. (2004). Activity theory as a basis for the study of work. Ergonomics, 47, 134–153.

- Cole, , & Engeström, Y. (1993). A cultural historical approach to distributed cognition. In G. Salomon (Ed.), Distributed cognitions: Psychological and educational considerations (pp. 1–46). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Collins, R. (2004). Interaction ritual c Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Engeström, Y., Miettinen, , & Punamäki, R.-L. (Eds.). (1999). Perspectives on activity theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Fuentes , Gómez-Sanz, J. J., & Pavón, J. (2004). Activity theory for the analysis and design of multi-agent systems. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2935, 110–122.

- Holzkamp, (1991). Societal and individual life processes.

- In C. W. Tolman & W. Maiers (Eds.), Critical psychology: Contributions to an historical science of the subject (pp. 50–64). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Kaptelinin, V., & Nardie, (1997). Activity theory: Basic concepts and applications. Retrieved from http://www.acm.org/sigchi/chi97/proceedings/tutorial/bn.htm

- Leont’ev, A. (1978). Activity, consciousness and personality. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Luria, A. R. (1976). Cognitive development: Its cultural and social foundations. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

- Nardi, (Ed.). (1996). Context and consciousness: Activity theory and human-computer interaction. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Ratner, C. (n.d.). Activity as a key concept for cultural psychology. Retrieved from http://www.humboldt1.com/~cr2/htm

- Roth, W. (2003). Toward an anthropology of graphing: Semiotic and activity-theoretic perspectives. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic.

- Roth, W. (Ed.). (2004). Activity theory in education. Mind, Culture, & Activity, 11(special issue), 1–77.

- Ryder, M. (n.d.) Activity theory. Retrieved from http://cudenver.edu/~mryder/itc_data/activity.html

- Sewell, W. (1992). A theory of structure: Duality, agency and transformation. American Journal of Sociology, 98, 1–29.

- Tolman, W. (1994). Psychology, society, and subjectivity: An introduction to German critical psychology. New York: Routledge.