Adolescence is the transitional period of growth, development, and maturation that begins at the end of childhood (about 10 years of age). The onset of puberty can begin as early as age 8 or as late as age 15 in girls and as early as age 9.5 years and as late as age 15 in boys. It is the defining marker of the start of adolescence. The end of adolescence generally occurs between the ages of 17 and 21 years and is marked by the individual reaching full physical and developmental maturity or young adulthood. This developmental phase involves significant physical, hormonal, cognitive, emotional, and social changes. A neurodevelopmental perspective of adolescence holds that most changes occur occurs in three overlapping stages: early, middle, and late. Early adolescence marks the onset of puberty, middle adolescence is characterized by peak growth and physical maturation, and late adolescence marks the end of puberty and the integration of all functional skills. The concept of adolescence is primarily a product of Western culture where youth are viewed as needing a time to mature from being children to taking on the responsibilities, values, and norms exhibited by the adults in their culture.

Developmental Process

A neurodevelopmental view of adolescent development involves examining how the human grows and matures with respect to the component skills necessary to perform various age-appropriate tasks. Those components are referred to as the functional domains. The developmental or maturational process of youth occurs across several distinct functional domains, is not always even, but is sequential; however, there is individual variation in the manifestation of that process. The skills learned and mastered are commonly divided into several functional domains: physical, motor, visual, auditory, perceptual, language, cognitive, psychosocial, and specific integrative-adaptive. All basic skills in these domains are mastered by the end of childhood in the normally developing individual.

Physical and psychological trauma, as well as deficits in any of the functional domains, can impede normal development.

Physical Growth and Development

The physical growth of young adolescents involves significant changes in the height, weight, and brain development that are exceeded only during two other time periods: when the fetus is in utero and between the ages of 1 and 3 years. Although 75% of brain growth (in weight) has developed by age 2, the process of central nervous system maturation takes place over a lifetime.

Motor Skills Development

The motor skills domain includes all fine and gross motor skills. Fine motor skills include precise, specific, and fine neuromotor responses such as pincer grasp and the ability to write legibly, cut paper designs with scissors, button, fasten, sew, draw match-to-sample designs, and control motor responses (i.e., tics, tremors, fidgeting, jerky motions, uncontrolled motions). Gross motor skills usually refer to whole body movement, including coordination of skeletal muscles, postural control, balance, coordination of motor planning, agility, muscular strength, and endurance (examples of such skills include the ability to hop, skip, jump, walk, run, crawl, walk a balance beam, walk a straight line toe to toe—forwards and backwards—throw, catch, and hit an object with another object).

Visual Skills Development

Visual skills include visual acuity, the ability to make discriminations between visual stimuli, the ability to track moving or still objects, color vision, extraocular muscle control, which includes resting balance of the eyes, control of eye movement, and visuomotor coordination (looking in different directions and seeing).

Communication Skills Development

Auditory Skills Development

The auditory domain refers to an individual’s ability to have “normal” hearing acuity, the ability to process what one hears, and the ability to employ selective discrimination of sounds and auditory cues.

Language Skills Development

The language domain skills (or the ability to communicate) involve two major areas: receptive and expressive language skills. Receptive language is the ability to understand spoken, signed, or written language and the ability to discriminate meanings and understand semantics and syntax. Expressive language refers to the ability to communicate effectively through spoken, signed, or written language.

The resultant neurobiological changes in childhood and adolescence are immense. For example, changes in the brain dealing with speech and language skills accelerate and peak in early adolescence; acquisition skills for a second language diminish after that.

Cognitive Skills Development

Cognitive skills refer to multiple facets of brain function including (1) the ability to pay and sustain attention that is required to focus selectively and generally on events, actions, and information in the environment; (2) the ability to be alert, which involves mental processing speed, and the ability to respond effectively to environmental cues and stimuli that cause or allow appropriate behavioral adaptation, which facilitates optimal positive outcomes and minimizes negative outcomes; (3) the ability to employ memory skills that include acquiring, storing, and recalling information; (4) the ability to use thinking skills, which means that the individual has knowledge of specifics (store, recall, retrieve), is able to comprehend information (oral, written, and through all senses), and can apply, analyze, synthesize, and evaluate that information; (5) the ability to solve problems and make decisions; and (6) the ability to perform multiple cognitive and functional tasks simultaneously.

Perceptual Motor Skills Development

Perceptual motor skills refer to the ability of the individual to experience a stimulus, process that information in the brain, and employ specific cognitive skills to determine the correct response and then execute the response. Such action requires the integration of stimulus-specific responses from the functional domains, such as visuospatial discrimination, which includes (1) eye–hand coordination, (2) stereognosis, (3) judgment of speed, (4) discrimination of the direction of the movement of people or their body parts or objects, and (5) spatial orientation of moving objects. Additional perceptual motor skills include temporal sequencing (the awareness of sequential ordering; awareness of time and sequence of events), proprioceptive sense, kinesthetic sense, and reaction time (time elapsed between stimulus perception and initial neuromotor response). Successful maturation of this domain means that the individual is able to synthesize all the other domains ( physical, cognitive, visual, language domains), which results in the adolescent having the ability to perceive, interpret, plan, and execute an appropriate neuromotor response to stimuli in the environment, and includes coordination, balance, agility, reaction time, and visuomotor responses. Because the perceptual and motor systems are mutually calibrated, any actions by the adolescent are constantly being fine tuned. The ability to see, hear, think, and move are important but are significantly affected by a person’s level of perceptual motor development. This ability begins at birth—children begin to learn to coordinate and integrate their physical, cognitive, visual, auditory, and language skills from birth. Being able to perform the basic motor skills but not being able to plan complex motor functions and not having a well-developed visual skill of tracking can result in awkward or clumsy behavior.

Psychosocial Skills Development

Psychosocial skills include the emotional and social functional skills required to allow an adolescent to cope with others and how he or she perceives the world emotionally. Emotional skills include the adolescent’s ability to exhibit emotions appropriate to situation or circumstances, the ability to monitor emotion, and the ability to regulate emotions. Social skills include the ability to initiate, develop, and sustain friendships; the ability to develop healthy interpersonal relationships with others; the ability to establish and maintain mutually beneficial intimate relationships; the ability to be empathetic; and the ability to be altruistic. Social skills also include the adolescent’s ability to adopt the moral values of his or her culture and of the greater society. Youth who are moral can use appropriate judgment to discriminate right from wrong and develop a sense of morality.

Integrative and Adaptive Skills Development

The final functional domain is the task-specific integrative and adaptive skills development domain. This domain involves the ability to coordinate, integrate, and adapt various domains to meet the specific demands of a given task or situation.

Developmental Stages Of Adolescence

Rational for this Perspective

Addressing adolescent development from a neurodevelopmental perspective helps one to understand the complexities of the maturational process of normal growth and development. Although this section is geared toward normal development, it is easier to realize how deficits in one functional domain can affect the function of other domains. During the first 10 years of life, most of the changes in the developing human evolve around physical, visual, motor, and language development; skills acquisition is the primary focus. During adolescence, new skills are acquired, but the focus shifts to refinement and expansion.

Adolescents who experience normal development will be able to integrate all functions of each domain and use those skills to successfully adapt to the demands of the environment in which they live. Youth who experience the complex process of maturation and growth normally achieve mastery and integration of these processes by late adolescence (ages 17–21 years).

Early Adolescence (Ages 10–14 Years)

With the onset of puberty, most adolescents begin to experience a physical growth spurt and begin sexual maturation resulting in significant changes across all domains of function. Some youth experience a “disconnect” between what they are experiencing developmentally and where they are placed in the school setting. There are often major differences across all domains between the abilities of a 10 year old and those of a 14 year old; additionally, because these youth are experiencing other transitions (e.g., going from elementary to middle to high school), they have to adjust to these environmental issues at the same time they are adjusting to biologic and physiologic changes.

Physical Growth and Development

The onset of puberty causes the adolescent to gain 25% of his or her final adult height (up to 10 cm per year), gain 50% of the ideal adult body weight; experience the doubling of major organs, maturation of facial bones, decrease in lymphoid tissue, genital maturation, primary and secondary sex characteristics, and central nervous system (CNS) maturation, triggering a rise in sex hormones including adrenal hormones, estrogen (female hormone), and testosterone (male hormone). The most significant physical changes of puberty involve a sequential increase in the genital system and secondary characteristics. These changes occur over a 2to 4-year period resulting in height velocity peak and growth of pubic hair. Females begin to develop breasts (thelarche), grow axillary hair, and menstruate. Males experience growth of pubic hair (pubarche), early testicular and penile growth, nocturnal emissions, marked voice changes, facial hair growth, and muscle development. It is not uncommon for girls to be taller and heavier than boys of the same age during early adolescence.

Brain Growth and Development

In addition to physical growth, the young adolescent undergoes CNS maturation without increase in brain size. The developing brain consists of billions of cells that are in place (by late fetal life). Neurological insults in early adolescence can have a major adverse impact on later development exposure to infections and toxins. Additionally, effects of these insults to the brain can be observed in young adolescents who were exposed to infections and toxins that damaged their brains in utero.

Other threats from the environment that can cause considerable brain injury result from violence exposure, malnutrition, poverty, and the adverse effects of chronic stress. Some experts hold that the developmental period of early adolescence offers a window of opportunity to repair damage or deficits in brain functioning or neurocortical connections. They offer that the brains of adolescents at this stage of development are repairable and say that because of the plasticity of brain tissue, brain cells have an astonishing capacity to adapt to changes and challenges that occur throughout life. Interventions designed to stimulate various functions of the brain may improve or influence the interconnectedness of brain cells or brain circuitry. Such environmental stimulation is also important because the young adolescent is undergoing profound CNS changes. Therefore, there are still enough redundant functions to allow for retraining of the brain to develop skills using previously unused portions of the brain in adolescents who may have suffered some types of brain injury.

Motor, Visual, and Auditory Development

All basic gross motor skills are developed by this stage. Youth are better able to maneuver their fine motor skills. Visual acuity, discrimination, tracking, color vision, and extraocular muscle control are all fully developed as youth enter this stage of development.

Auditory Development

The ability to hear is present at birth but is refined and fully developed by the end of this developmental stage. Components that contribute to this refinement are acuity, the ability to selectively process and discriminate between sounds, and the selective discrimination of written language.

Perceptual Motor Development

Basic perceptual motor skills such as those that allow for integrated stimulus-specific fine motor and gross motor responses, visuospatial discrimination, eye–hand coordination, and stereognosis are developed at a basic level by age 10 or during childhood. Maturation results in refinement of those skills and improved judgment of speed, direction, and spatial orientation of moving objects.

Language Development

All basic receptive and expressive language functions are in place. Further development, practice, exposure, and training result in improved language and communication skills.

Cognitive Skills

These youth are beginning the cognitive refinement process. Although most young adolescents still engage in “concrete” thinking (“here and now,” “right or wrong,” “black or white”), their ability to perform more complex mental tasks (thinking skills and problem-solving skills) is increasing. They have a clear sense of justice, know right from wrong, and may have an awakening sense of morality and altruism. However, they cannot project future outcomes nor always see abstract relationships between their behavior and potential risks. They have improved mental processing speed and alertness, longer attention spans, and better judgment. They are beginning to understand the purpose of the rules they learned earlier. They understand and can apply factual knowledge to familiar situations but may not be able to apply that knowledge to unique or different situations. They can understand and answer more complex questions as their vocabulary increases and their ability to distinguish between the similarities and differences improves; they can complete simple analogies and are beginning to develop inductive and deductive reasoning abilities. They are able to adopt another person’s spatial perspective with ease and can describe the arrangement of objects from another person’s point of view. They are developing prepositional logic in which they can think about thinking itself. These adolescents are also able to enjoy and take pride in increasingly complex accomplishments, which positively contributes to developing and strengthening a healthy self-image. Their difficulty with futuristic thinking affects their ability to think about the consequences of their behavior before they act. They often engage in “magical thinking” or the belief that they have unique powers that will protect them from harm. Therefore, they are at increased risk for accident related morbidity and mortality.

Psychosocial Development

Emotionally, because they are preoccupied with the rapid physiological changes of puberty, these young adolescents may experience feelings of confusion and worry about what is happening to them. They may seem forgetful, distracted, moody, and hypochondriacal, often complaining about body aches or pains. They generally know it is not okay to make fun of others in public. They can control their anger or hurt feelings when they cannot get their own way, are teased by siblings or peers, or are rejected by others. Many adolescents begin to experience emotional distress and conflict when they are trying to decide whether to follow the values of their peers or their families. However, the approval and support from family (especially parents) remains a crucial feature of their healthy development and resilience. Socially, they have a clear sense of their own body image and social standing with their peers; they can accurately discriminate between peers who are popular or “smart” and those who are not. Although most young adolescents do not engage in unhealthy behaviors, too many do. The outcome of such experimentation can result in a significant level of morbidity and mortality.

Socially, developing and maintaining peer relationships and cognitive skills to cope with emotions and social situations are crucial during this stage of maturation. Friendships tend to be one at a time or with unisexual cliques; peer acceptance is of increasing importance and influence. Because they are keenly aware of their own body image and are sensitive to the criticism of others, the high incidence of bullying and teasing that occurs at this age can have a significant impact on how the young adolescent feels about himself or herself and responds to his or her environment.

Parent–Adolescent Relationships

Parents may frequently be perplexed by their adolescent’s rapid mood changes, secretiveness, challenging, telling lies, or refusal to give straight answers. Because the young adolescent is experiencing so many simultaneous changes (physical, hormonal, biological, emotional, and social), it is essential that parents, teachers, and other care providers be patient and help guide them through techniques to manage their emotions, helping them expand their critical thinking and problem-solving skills. In this manner, these youth can learn conflict resolution and self-soothing skills that will allow them to manage their distress and family conflict while improving their self-confidence.

Middle Adolescence (Ages 14–17 Years)

The middle stage of adolescence spans ages 14 to 17 and encompasses the middle school (8th grade) and high school years.

Physical Development

Most adolescents experience continued increases in specialization of gross motor skills, muscle mass, strength, and cardiopulmonary endurance. Some adolescents may find it difficult to adjust to the somatic growth spurt, which may result in temporary clumsiness or awkwardness. Some youth may become very concerned about their normal increases in body weight and size. This may result in excessive dieting and exercise, purging, or other pathogenic weight control measures.

Motor, Visual, and Auditory Development

All skills in these domains are fully developed at the end of middle adolescence, with the exception of the pincer grasp, which continues to develop in late adolescence. As with other domains of function, however, practice and training can further refine these skills.

Language Development

By the end of middle adolescence, youth have mature language skills and can improve on their language abilities with training and practice.

Cognitive Development

Cognitively, these youth can independently weigh consequences of their decisions before taking action; they can engage in fantasy, develop theories about life, and think about what they would like to do when they become adults. Their ability to engage in inductive and deductive reasoning is expanding.

Perceptual Motor Development

All perceptual motor skills are fully developed by the end of this stage. Practice and training can help further refine such abilities.

Psychosocial Development

Although most adolescents move through this developmental stage with minimal distress and problems, some struggle with fluctuating moods and emotions, the impact of which ranges from transient to debilitating. Some youth begin to develop unhealthy behaviors related to weight control practices, eating disorders, substance or alcohol use or abuse, questions about their sexual identity, or sexual activity.

Although these youth have the language skills and cognitive skills to solve problems, rationalize, and understand what is happening to them, they do not have the life experiences to know that their distress is temporary and transitional. This lack of experiential knowledge and coping skills could result in the adolescent running away from home, attempting suicide, engaging in self-mutilation, failing school, or engaging in other high-risk behaviors.

These adolescents may know and understand the consequences of risk-taking behaviors, but their caution may be overridden by their stronger need for popularity and peer recognition. Such negative adaptations may present significant problems for some adolescents. They may become preoccupied with comparing their physical characteristics with peers’, and thinking about sexual relationships may occupy much of their time. As adolescents consistently experience success, they tend to develop a positive self-image and increased confidence. Because of their limited life experiences, adolescents may remain highly sensitive to negative comments from others, peer rejection, bullying, and traumatic personal experiences. As these youth begin to date and have increased sexual desires, they may have sexual fantasies. Some youth will fantasize about same-sex peers and become very disturbed over these events. They may need reassurance that this does not denote sexual orientation. Other youth are beginning to clearly know their sexual orientation. Youth who realize they are gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgendered may begin to experience mental distress in reaction to fears of being discovered and rejected by their family and peers. Youth who are older or younger than their grade peers may experience psychosocial and emotional problems. Violence and substance use or abuse may become prominent parts of the lives of some youth, increasing their risk for pregnancy, substance abuse, academic failure, injury, or even death (Table 1).

Table 1 Behaviors That Increase the Risk for Morbidity and Mortality

Parent–Adolescent Relationships

During middle adolescence, youth continue to develop their independence from parents and authority figures. Adolescents now begin to rely more and more on peers as their frames of reference. They use peer feedback to set personal goals and rules of conduct. They are capable of multiple relationships. Their feelings are often very intense and may increase their tendency to engage in risky behavior, argue, or challenge authority.

Emancipation

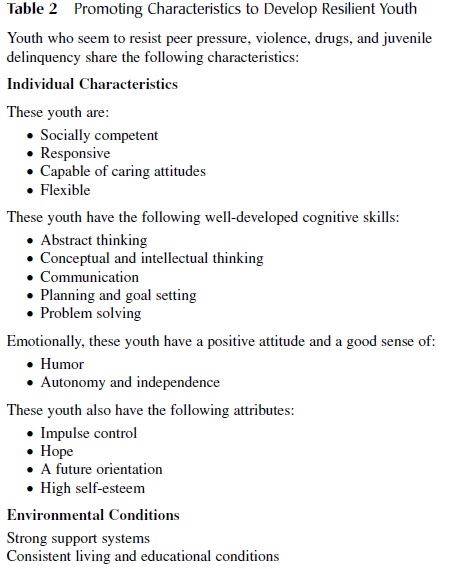

Adolescents at this stage of development have the requisite skills to recognize and understand the demands of a particular academic activity, field of study, social endeavor, or sport and can decide whether they want to engage in the necessary behaviors to meet those requirements. Exposure to multiple exploratory activities that are healthy will improve the adolescent’s opportunities to be successful and understand personal needs, desires, and limitations (Table 2). Issues related to sexuality, substance use, and healthy lifestyle need to be clearly and directly addressed by parents. It is important that parents remember that they retain considerable influence over their adolescents so that they do not give up on their children.

Table 2 Promoting Characteristics to Develop Resilient Youth

Table 2 Promoting Characteristics to Develop Resilient Youth

Late Adolescence (Ages 17–21 Years)

During this stage of development, adolescents are facing high school graduation, placement tests, and often college or career selection activities. They are expected to make major decisions about the rest of their lives. By the end of late adolescence, most youth reach full physical, cognitive, social, and emotional maturity, and most issues of emancipation are essentially resolved.

Physical Development

Specialization of gross motor skills, gains in strength, and aerobic capacity are fully developed; however, some adolescents may continue to develop speed and increase in size; these changes occur at a slower rate compared with during middle adolescence, and females continue to accumulate fat mass. Their vision is fully developed.

Cognitive Motor Development

These youth engage in more complex cognitive skills. Abstract thought has been established, empathy skills are well developed, and personal values are clearer and well defined. Youth are able to process and make adult decisions, are future oriented, and perceive, set, and react on long-range options and goals. They have the cognitive ability to understand and remember strategies for most academic, sports, and life endeavors.

Psychosocial Development

These youth are continuing the process of emancipation and their significant symbolic movement away from home. Some adolescents seek employment, move away from home, and become financially independent. Others go to college and only temporarily move from their parents’ home and continue to be financially and emotionally dependent on their parents. Other youth may choose some combination of these two scenarios. Adolescents in the late stages of development are beginning to resolve conflicts between themselves and their parents. At this stage, youth should have developed an acceptable body image and gender role. They continue to develop their ability to function independently and are less influenced by peers; now they can think independently and use their own judgment for setting personal rules. They are more actively participating in sexual experimentation, are able to be altruistic, and can initiate, develop, and sustain intimate relationships. Their relationships with romantic partners are less narcissistic and more geared toward mutual respect and gratification. They prefer the association with groups and couples and prefer intimacy versus isolation. Most adolescents at this stage of maturation have developed a strong sense of personal identity.

Summary

A neurodevelopmental perspective of adolescence holds that it is a transitional period of growth, development, and maturation that begins at the end of childhood and ends with entry into adulthood (about between the ages of 10 and 21 years). The onset of puberty signals the start of adolescence. The end of adolescence is marked by the individual reaching full physical and developmental maturity or young adulthood. As adolescents matriculate through this phase of life, they experience significant physical, hormonal, cognitive, emotional, and social changes. These changes occur in three overlapping stages: early, middle, and late adolescence. Early adolescence marks the onset of puberty, middle adolescence is characterized by peak growth and physical maturation, and late adolescence marks the end of puberty and the integration of all functional skills. Youth who experience normal growth and development phase through these stages with minimal problems and emerge a fully functioning member of society.

References:

- Abe, A., & Izard, C. E. (1999). A longitudinal study of emotion, expression and personality relations in early development. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(3), 566–577.

- Blos, P. (1962). On adolescence. Glencoe, NY: Free Press. Centers for Disease Control and Prev (2001). School health guidelines to prevent unintentional injuries and violence. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 50, RR22. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ rr5022a1.htm

- Erickson, E. (1963). Childhood and society. New York: W. W.

- Erickson, (1968). Identity, youth and crisis. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Gemelli, (1996). Normal child and adolescent development. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Gesell, , Ilg, F. L., & Ames, L. B. (1946). The child from five to ten. New York: Harper & Row.

- Gomez, E. (2000). Growth and maturation. In A. J. Sullivan& S. J. Anderson (Eds.), Care of the young athlete (pp. 25–32). Park Ridge, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, and Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Greydanus, E., Pratt, H. D, & Patel, D. R. (2004). The first three years of life and the early adolescent: Influences of biology and behavior-implications for child rearing. International Pediatrics, 19(2), 70–78.

- Grunbaum, A., Kann, L., Kinchen, S. A., Williams, B., Ross, J. G., Lowry, R., et al. (2002). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2001. Morbidity and Mortality

- Weekly Report, 51(SS04), 1–64. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss5104a1.htm

- Hofmann, D. (1997). Adolescent growth and development.In A. D. Hofmann & D. E. Greydanus (Eds.), Adolescent medicine (3rd ed., pp. 11–22). Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange.

- Kreipe, R. E. (1994). Normal somatic adolescent growth and dev In E. R. McAnarney, R. E. Kreipe, D. P. Orr,& G. D. Comerci (Eds.), Textbook of adolescent medicine (pp. 44–67). Philadelphia: WB Saunders.

- Levine, M. D. (2000). Neurodevelopmental dysfunction in the school age In R. E. Behrman, R. M. Kliegman, & H. B. Jenson (Eds.), Nelson textbook of pediatrics (16th ed., pp. 94–100). Philadelphia: WB Saunders.

- Piaget, J. (1972). Intellectual evaluation from adolescence to adulthood. Human development 15(1), 1–12.

- Piaget, , & Inhelder, B. (1969). The psychology of the child. New York: Basic Books.

- Pratt, H. D. (2002). Neurodevelopmental issues in the assessment and treatment of deficits in attention, cognition, and learning during adolescence. Adolescent Medicine: State of the Art Reviews, 13(3), 579–598.

- Resnick, D., Bearman, P. S., Blum, R. W., Bauman, K. E., Harris, K. M., Jones, J., et al. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278, 823–832.

- Rice, F. P. (1978). The period of The adolescent: Development, relationships and culture (2nd ed., pp. 52–85). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.