Attachment theory is a psychological and developmental framework that explores the impact of early relationships on an individual’s emotional, social, and cognitive development. It was first proposed by British psychologist John Bowlby in the 1950s and has since become one of the most influential theories in understanding human behavior and relationships. This theory suggests that the quality of a child’s early attachment to their primary caregiver shapes their ability to form and maintain relationships in the future. By examining the dynamics of attachment, we can gain insight into how our early experiences with caregivers influence our sense of self, ability to regulate emotions, and overall well-being. In this short introduction, we will delve into the key concepts of attachment theory and its relevance in understanding human behavior.

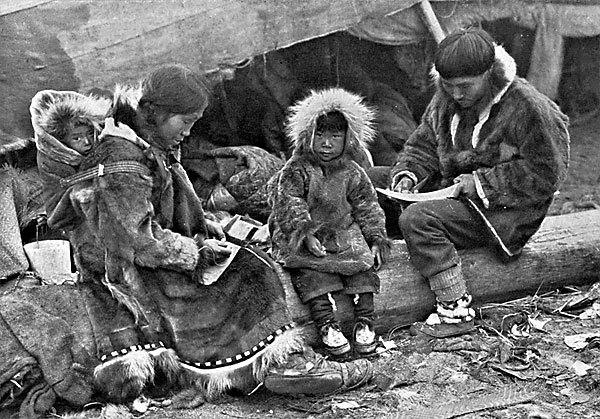

An Inuit family is sitting on a log outside their tent. The parents, wearing warm clothing made of animal skins, are engaged in domestic tasks. Between them sits a toddler, also in skin clothes, staring at the camera. On the mother’s back is a baby in a papoose.

For infants and toddlers, the “set-goal” of the attachment behavioural system is to maintain or achieve proximity to attachment figures, usually the parents.

Attachment theory describes the dynamics of long-term relationships between humans. Its most important tenet is that an infant needs to develop a relationship with at least one primary caregiver for social and emotional development to occur normally. Attachment theory is an interdisciplinary study encompassing the fields of psychological, evolutionary, and ethological theory. Immediately after WWII, homeless and orphaned children presented many difficulties, and psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby was asked by the UN to write a pamphlet on the matter. Later he went on to formulate attachment theory.

Infants become attached to adults who are sensitive and responsive in social interactions with them, and who remain as consistent caregivers for some months during the period from about six months to two years of age. When an infant begins to crawl and walk they begin to use attachment figures (familiar people) as a secure base to explore from and return to. Parental responses lead to the development of patterns of attachment; these, in turn, lead to internal working models which will guide the individual’s perceptions, emotions, thoughts and expectations in later relationships. Separation anxiety or grief following the loss of an attachment figure is considered to be a normal and adaptive response for an attached infant. These behaviours may have evolved because they increase the probability of survival of the child.

Infant behaviour associated with attachment is primarily the seeking of proximity to an attachment figure. To formulate a comprehensive theory of the nature of early attachments, Bowlby explored a range of fields, including evolutionary biology, object relations theory (a branch of psychoanalysis), control systems theory, and the fields of ethology and cognitive psychology. After preliminary papers from 1958 onwards, Bowlby published a complete study in 3 volumes Attachment and Loss (1969–82).

Research by developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth in the 1960s and 70s reinforced the basic concepts, introduced the concept of the “secure base” and developed a theory of a number of attachment patterns in infants: secure attachment, avoidant attachment and anxious attachment. A fourth pattern, disorganized attachment, was identified later.

In the 1980s, the theory was extended to attachment in adults. Other interactions may be construed as including components of attachment behaviour; these include peer relationships at all ages, romantic and sexual attraction and responses to the care needs of infants or the sick and elderly.

In the early days of the theory, academic psychologists criticized Bowlby, and the psychoanalytic community ostracised him for his departure from psychoanalytical tenets; however, attachment theory has since become “the dominant approach to understanding early social development, and has given rise to a great surge of empirical research into the formation of children’s close relationships”. Later criticisms of attachment theory relate to temperament, the complexity of social relationships, and the limitations of discrete patterns for classifications. Attachment theory has been significantly modified as a result of empirical research, but the concepts have become generally accepted. Attachment theory has formed the basis of new therapies and informed existing ones, and its concepts have been used in the formulation of social and childcare policies to support the early attachment relationships of children.

Attachment

A young mother smiles up at the camera. On her back is her baby gazing at the camera with an expression of lively interest.

Although it is usual for the mother to be the primary attachment figure, infants will form attachments to any caregiver who is sensitive and responsive in social interactions with them.

Within attachment theory, attachment means an affectional bond or tie between an individual and an attachment figure (usually a caregiver). Such bonds may be reciprocal between two adults, but between a child and a caregiver these bonds are based on the child’s need for safety, security and protection, paramount in infancy and childhood. The theory proposes that children attach to carers instinctively, for the purpose of survival and, ultimately, genetic replication. The biological aim is survival and the psychological aim is security. Attachment theory is not an exhaustive description of human relationships, nor is it synonymous with love and affection, although these may indicate that bonds exist. In child-to-adult relationships, the child’s tie is called the “attachment” and the caregiver’s reciprocal equivalent is referred to as the “care-giving bond”.

Infants form attachments to any consistent caregiver who is sensitive and responsive in social interactions with them. The quality of the social engagement is more influential than the amount of time spent. The biological mother is the usual principal attachment figure, but the role can be taken by anyone who consistently behaves in a “mothering” way over a period of time. In attachment theory, this means a set of behaviours that involves engaging in lively social interaction with the infant and responding readily to signals and approaches. Nothing in the theory suggests that fathers are not equally likely to become principal attachment figures if they provide most of the child care and related social interaction.

Some infants direct attachment behaviour (proximity seeking) towards more than one attachment figure almost as soon as they start to show discrimination between caregivers; most come to do so during their second year. These figures are arranged hierarchically, with the principal attachment figure at the top. The set-goal of the attachment behavioural system is to maintain a bond with an accessible and available attachment figure. “Alarm” is the term used for activation of the attachment behavioural system caused by fear of danger. “Anxiety” is the anticipation or fear of being cut off from the attachment figure. If the figure is unavailable or unresponsive, separation distress occurs. In infants, physical separation can cause anxiety and anger, followed by sadness and despair. By age three or four, physical separation is no longer such a threat to the child’s bond with the attachment figure. Threats to security in older children and adults arise from prolonged absence, breakdowns in communication, emotional unavailability or signs of rejection or abandonment.

Behaviours

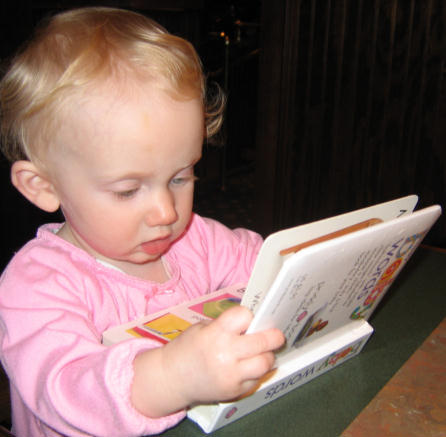

A baby leans at a table staring at a picture book with intense concentration.

Insecure attachment patterns can compromise exploration and the achievement of self-confidence. A securely attached baby is free to concentrate on her or his environment.

The attachment behavioural system serves to maintain or achieve closer proximity to the attachment figure. Pre-attachment behaviours occur in the first six months of life. During the first phase (the first eight weeks), infants smile, babble and cry to attract the attention of caregivers. Although infants of this age learn to discriminate between caregivers, these behaviours are directed at anyone in the vicinity. During the second phase (two to six months), the infant increasingly discriminates between familiar and unfamiliar adults, becoming more responsive towards the caregiver; following and clinging are added to the range of behaviours. Clear-cut attachment develops in the third phase, between the ages of six months and two years. The infant’s behaviour towards the caregiver becomes organised on a goal-directed basis to achieve the conditions that make it feel secure. By the end of the first year, the infant is able to display a range of attachment behaviours designed to maintain proximity. These manifest as protesting the caregiver’s departure, greeting the caregiver’s return, clinging when frightened and following when able. With the development of locomotion, the infant begins to use the caregiver or caregivers as a safe base from which to explore. Infant exploration is greater when the caregiver is present because the infant’s attachment system is relaxed and it is free to explore. If the caregiver is inaccessible or unresponsive, attachment behaviour is more strongly exhibited. Anxiety, fear, illness and fatigue will cause a child to increase attachment behaviours. After the second year, as the child begins to see the carer as an independent person, a more complex and goal-corrected partnership is formed. Children begin to notice others’ goals and feelings and plan their actions accordingly. For example, whereas babies cry because of pain, two-year-olds cry to summon their caregiver, and if that does not work, cry louder, shout or follow.

Tenets

Common human attachment behaviours and emotions are adaptive. Human evolution has involved selection for social behaviours that make individual or group survival more likely. The commonly observed attachment behaviour of toddlers staying near familiar people would have had safety advantages in the environment of early adaptation, and has such advantages today. Bowlby saw the environment of early adaptation as similar to current hunter-gatherer societies. There is a survival advantage in the capacity to sense possibly dangerous conditions such as unfamiliarity, being alone or rapid approach. According to Bowlby, proximity-seeking to the attachment figure in the face of threat is the “set-goal” of the attachment behavioural system.

The attachment system is very robust and young humans form attachments easily, even in far less than ideal circumstances. In spite of this robustness, significant separation from a familiar caregiver—or frequent changes of caregiver that prevent the development of attachment—may result in psychopathology at some point in later life. Infants in their first months have no preference for their biological parents over strangers. Preferences for certain people, plus behaviours which solicit their attention and care, are developed over a considerable period of time. When an infant is upset by separation from their caregiver, this indicates that the bond no longer depends on the presence of the caregiver, but is of an enduring nature.

Early experiences with caregivers gradually give rise to a system of thoughts, memories, beliefs, expectations, emotions and behaviours about the self and others.

Bowlby’s original sensitivity period of between six months and two to three years has been modified to a less “all or nothing” approach. There is a sensitive period during which it is highly desirable that selective attachments develop, but the time frame is broader and the effect less fixed and irreversible than first proposed. With further research, authors discussing attachment theory have come to appreciate that social development is affected by later as well as earlier relationships. Early steps in attachment take place most easily if the infant has one caregiver, or the occasional care of a small number of other people. According to Bowlby, almost from the first many children have more than one figure towards whom they direct attachment behaviour. These figures are not treated alike; there is a strong bias for a child to direct attachment behaviour mainly towards one particular person. Bowlby used the term “monotropy” to describe this bias. Researchers and theorists have abandoned this concept insofar as it may be taken to mean that the relationship with the special figure differs qualitatively from that of other figures. Rather, current thinking postulates definite hierarchies of relationships.

Early experiences with caregivers gradually give rise to a system of thoughts, memories, beliefs, expectations, emotions, and behaviours about the self and others. This system, called the “internal working model of social relationships”, continues to develop with time and experience. Internal models regulate, interpret and predict attachment-related behaviour in the self and the attachment figure. As they develop in line with environmental and developmental changes, they incorporate the capacity to reflect and communicate about past and future attachment relationships. They enable the child to handle new types of social interactions; knowing, for example, that an infant should be treated differently from an older child, or that interactions with teachers and parents share characteristics. This internal working model continues to develop through adulthood, helping cope with friendships, marriage and parenthood, all of which involve different behaviours and feelings. The development of attachment is a transactional process. Specific attachment behaviours begin with predictable, apparently innate, behaviours in infancy. They change with age in ways that are determined partly by experiences and partly by situational factors. As attachment behaviours change with age, they do so in ways shaped by relationships. A child’s behaviour when reunited with a caregiver is determined not only by how the caregiver has treated the child before, but on the history of effects the child has had on the caregiver.