There is an adage, “Give people a fish and they eat for a day, but teach them to fish and they eat for a lifetime.” This wise maxim succinctly captures the ultimate aim of the cognitive information processing (CIP) approach to career counseling—that is, enabling individuals to become skillful career problem solvers and decision makers. Through the CIP approach, individuals learn not only how to solve the immediate career problem and make an appropriate decision, but also how to generalize this experience to future career problems.

In the 1970s, a line of inquiry emerged from the cognitive sciences that offered a new way of thinking about problem solving and decision making. This paradigm, known as CIP, was initially formulated in the works of Earl Hunt, Allen Newell and Herbert Simon, and Roy Lackman, Janet Lackman, and Earl Butterfield. When applied to career choices, this paradigm, herein referred to as the CIP model, provides a way to describe the fundamental memory structures and thought processes involved in solving career problems and making career decisions. With the CIP model, career counselors can assist clients in becoming better career problem solvers and decision makers.

The CIP model is described in four sections. The first presents key concepts that form its foundation, the second discusses assessing client needs from a CIP perspective, the third describes interventions consistent with this theoretical frame, and the fourth concerns the application of the model in career counseling practice.

Definitions and Concepts

The following are key definitions in the CIP model to facilitate the understanding and utility of the approach.

Career problem: A gap between an existing state of career indecision and a more desirable state of decidedness. The gap creates a state of cognitive dissonance that becomes the primary motivational force driving the problem-solving process. The presence of a gap results in tension or discomfort that individuals seek to eliminate through problem solving and decision making.

Problem space: All cognitive and affective components contained in working memory as individuals approach a career problem-solving task. In clients’ lives, the problem space entails the career problem at hand, in addition to all the issues associated with it such as marital and family relationships, financial exigencies, and the emotional states embedded in them.

Career problem solving: A complex set of thought processes involved in acknowledging a gap, analyzing its causes, formulating and clarifying alternative courses of actions, and selecting one alternative to reduce the gap. A career problem is solved when a career choice is made from among the alternatives.

Career decision making: A process that not only encompasses career choice, but also entails a commitment to and the carrying out of the actions necessary to implement the choice.

Career development: The implementation of a series of career decisions that comprise an integrated career path throughout the life span.

The Pyramid of Information Processing and the CASVE Cycle

Two fundamental structures comprise the CIP model: the Pyramid of Information Processing and the CASVE Cycle.

The Pyramid of Information Processing

In order for individuals to become independent and responsible career problem solvers and decision makers, certain information processing capabilities must undergo continual development throughout the life span. These capabilities may be envisioned as forming a pyramid of information processing domains with three hierarchically arranged domains (see Figure 1). The knowledge domain lies at the base, the decision-making skills domain comprises the mid level, while the executive processing domain is at the apex.

The Knowledge Bases. Two knowledge domains, self-and occupational knowledge, lie at the base of the pyramid. Self-knowledge includes knowledge about one’s interests, abilities, skills, and values based on an ongoing construction of one’s life’s experiences. Occupational knowledge consists of one’s own unique structural representation of the world of work and an understanding of individual occupations in terms of their duties and responsibilities, as well as education and training requirements to attain them.

Figure 1. Pyramid of information processing domains in career decision making

Source: Sampson, J. P., Jr., Peterson, G. W., Lenz, J. G., & Reardon, R. C. (1992). A cognitive approach to career services: Translating theory into practice. Career Development Quarterly, 41, 67-72. Used with permission.

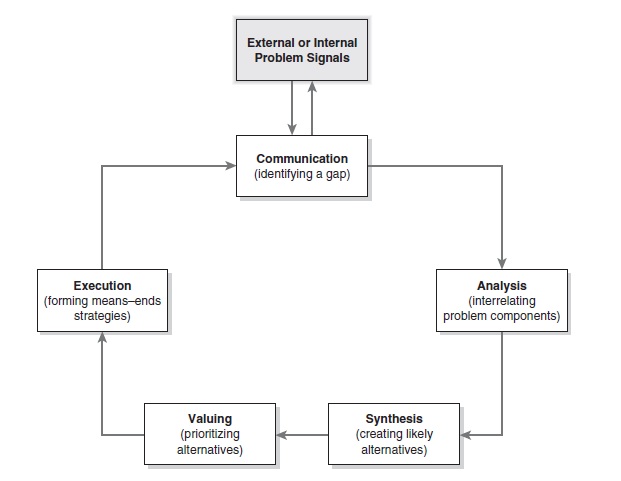

The CASVE Cycle. The midlevel of the Pyramid of Information Processing, referred to as the decision-making skills domain, involves generic information processing skills that combine occupational knowledge and self-knowledge to solve a career problem and to make a decision. A 5-phase recursive information transformation process (see Figure 2), the CASVE Cycle (pronounced “ca-sah-veh”), is used as an overarching heuristic to structure the career counseling process.

- Communication (C). An individual engages the career problem-solving process by receiving and encoding information that signals that a problem exists. One then queries oneself and the environment to formulate the gap (or discontinuity) that is the problem. This phase also entails getting in touch with all components of the problem space including thoughts, feelings, and related life circumstances.

- Analysis (A). The causes of the problem are identified and the relationships among problem components are placed in a conceptual framework or mental model.

- Synthesis (S). Possible courses of action to eliminate the gap are formulated through the creation of possibilities (synthesis elaboration) and then narrowed (synthesis crystallization) to a manageable set of viable alternatives.

- Valuing (V). Each course of action or alternative is evaluated and prioritized according to its likelihood of success in removing the gap and its probable impact on one’s self, significant others, cultural group, and society. Through this process a first choice emerges that has the highest prospect of removing the gap. The career problem is now solved.

- Execution (E). An action plan is formulated to implement the choice, which becomes a goal for the client. A series of milestones are laid out that will lead step-by-step to the attainment of the goal. Thus, a career decision is made when individuals move deliberately toward a goal, such as enrolling in an educational program or taking a job in a chosen occupational field.

Upon executing the plan, there is a return to the Communication phase of the cycle to evaluate whether the decision successfully removed the gap. If so, the individual moves on to solve succeeding problems that arise from the implementation of the solution. If not, one recycles through the CASVE Cycle with new information about the problem, one’s self, and occupations acquired from the initial pass through the CASVE Cycle. Hence, self-knowledge and occupational memory structures evolve with each pass through the cycle.

The Apex. The apex of the pyramid, the executive processing domain, contains metacognitive components that guide and regulate the lower-order cognitive functions. This domain can be referred to as thinking about thinking, which entails the ability to view one’s self as a career problem solver from a detached perspective. The domain involves metacognitive components that (a) control the selection and sequencing of cognitive strategies to achieve a goal, and (b) monitor the execution of a given problem-solving strategy to determine if a goal has been reached.

Figure 2. The five stages of the CASVE (Communication, Analysis, Synthesis, Valuing, Execution) Cycle of information processing skills used in career decision making

Source: Sampson, J. P., Jr., Peterson, G. W., Lenz, J. G., & Reardon, R. C. (1992). A cognitive approach to career services: Translating theory into practice. Career Development Quarterly, 41, 67-72. Used with permission.

Assessment of Client Learning Needs

Assessment from the CIP model perspective concerns what clients need to learn to enhance their career problem-solving and decision-making skills so as to effectively address the career problem at hand. The pyramid and the CASVE Cycle serve as heuristics for identifying client learning needs and formulating interventions to remove the gap.

Assessing Readiness for Career Problem Solving and Decision Making

Not all clients are prepared to immediately engage in the career problem-solving process—they may require intensive personal assistance from a career counselor to manage factors in the problem space that impede learning before they are able to progress through the cycle. Assessing client readiness may be accomplished through integrating information gathered via an intake interview and some type of objective assessment, for example, the Career Thoughts Inventory (CTI). The CTI is a 48-item, self-report measure that assesses the level of client’s dysfunctional thinking through three construct scales, Decision-Making Confusion (DMC), External Conflict (EC), and Commitment Anxiety (CA). Scale scores, along with responses to individual items, enable a career counselor, together with the client, to identify discrepancies in the pyramid or blocks in the CASVE Cycle that impede career problem solving and decision making. On the basis of the readiness assessment, clients may be assigned to one of three levels of career service: (1) self-help, (2) brief staff-assisted, and (3) individual case-managed career counseling.

Assessing Career Problem-Solving Skills

The assessment of problem-solving and decision-making skills entails identifying specific domains in the pyramid that require further development to enable a client to solve the career problem at hand and to make a decision.

Self-Knowledge. Assessing self-knowledge is often a confirmatory process in which interest inventories, such as the Self-Directed Search, allow clients to clarify and reaffirm their interests. Computer-assisted career guidance (CACG) systems, card sorts (values, interests, skills), and autobiographical sketches may also be useful.

Occupational Knowledge. Occupational knowledge may be assessed through vocational card sorts or by using a card sort as a cognitive mapping task. Through a think-aloud procedure, clients reveal their knowledge about occupations as they sort the cards into like, dislike, or maybe piles. In a cognitive mapping task, clients reveal a schema of the work world by sorting 36 occupational cards into piles of related occupations and then identifying the pile “Most like me.”

Decision-Making Skills. The CTI may be used to identify specific CASVE Cycle phases in which clients experience blocks in the career problem-solving process brought about by dysfunctional career thoughts. The DMC scale reveals dysfunction in the communication, analysis, and synthesis phases that entail deriving career alternatives; the EC phase addresses the valuing phase in which clients weigh the importance of their views in relation to views of significant others; and the CA scale alludes to reaching closure in identifying a first choice, as well as the transition from arriving at a career problem solution in the valuing phase to a commitment to action in the execution phase.

Executive Processing. Dysfunctional thoughts in this domain may also be assessed through responses to individual items on the Executive Processing content scale of the CTI. In addition, during the client interview a career counselor may listen carefully for instances of negative self-talk, ineffective cognitive strategies, and lack of thought or behavioral control in staying focused on the problem-solving task at hand.

The outcome of the assessment process is the development of an individualized learning plan (ILP) consisting of counseling goals to address the identified deficiencies and blocks that impede problem solving and decision making.

Interventions to Help Clients Acquire Career Problem-Solving and Decision-Making Skills

The pyramid and CASVE Cycle are instrumental in developing interventions that facilitate the acquisition of required self-knowledge, occupational knowledge, and career problem-solving and decision-making skills identified in the assessment process.

Acquiring Self-Knowledge

The acquisition or clarification of self-knowledge may be accomplished through the use of interest inventories, values inventories, and ability and skills assessments that typically affirm and clarify the elements of the self-knowledge domain. Autobiographies may also be helpful in describing and organizing life experiences that bear on the career problem at hand.

Acquiring Occupational Knowledge

In career counseling, clients engage in the processes of schema specialization in which they are able to make finer discriminations among occupations, as well as schema generalization in which they form more extensive networks of connections among extant occupational knowledge structures. When career counseling takes place within comprehensive career centers, the acquisition of occupational knowledge may be facilitated through the use of a variety of media, including occupational briefs, vocational biographies, reference books, special topics books, videos, interactive media, and Internet Web sites. Reality testing through job shadowing or interviews with job incumbents allows clients to experience occupations even more directly.

Acquiring Career Problem-Solving and Decision-Making Skills

The concept of the Pyramid of Information Processing Domains is presented directly to clients in a handout called “What’s Involved in Career Choice.” The concepts of communication, analysis, synthesis, valuing, and execution and the cyclical relationship among these concepts are learned via a handout depicting the CASVE Cycle, which uses simple statements to describe each phase. Then, through subsequent review of ILP activities and feedback from a counselor, clients begin to accommodate and assimilate the CIP model into their own decision-making style. At the termination of counseling, the counselor reviews the decision-making process undertaken and demonstrates how the CIP model can be used in future career problem situations.

Acquiring Metacognitive Skills in the Executive Processing Domain

When dysfunctional or negative thoughts are identified in the assessment process, clients learn how to change their dysfunctional or negative career thoughts using the ICAA algorithm (Identify, Challenge, Alter, and Act). The CTI Workbook takes clients step-by-step through a cognitive restructuring process. Clients also learn how to self-monitor their progress through the CASVE Cycle.

Implementing the Cognitive Information Processing Model in Career Counseling

The Seven-Step Sequence

A seven-step career service delivery sequence is used as a heuristic for implementing the CIP model in career counseling.

- Initial interview: The career counselor gathers qualitative self-report information about the nature of a client’s presenting career problem.

- Preliminary readiness assessment: An individual’s readiness for career counseling is assessed through administering the CTI. The findings are reviewed and discussed with the client.

- Define the problem and analyze the causes: The counselor and the client come to a mutual understanding or common mental model of the career problem and related issues. The specific causes of the problem lie in the deficiencies within the respective domains of the pyramid or blocks that impede progress through the CASVE Cycle.

- Formulate goals: The counselor and client together formulate a set of attainable goals, stated in behavioral terms, to remove the gap.

- Develop an ILP: For each goal, the counselor and client develop learning activities to attain the goal, resources used in the activities, estimated time to carry out the activities, and the priority for each activity.

- Execute ILP: Clients carry out the ILP while the counselor monitors the attainment of the respective goals and assists the client when required.

- Summative review and generalization: The client and counselor review the process used to solve the problem and make the decision at hand and evaluate its effectiveness. They also explore how the CIP model might be applied to future career problems or even to life problems in general.

Implications for Best Practices in Career Service Delivery

The CIP model advances the state-of-the-science in career counseling by providing a theory base for introducing a value-added dimension, that is, using the problem at hand as a means for furthering the acquisition of career problem-solving and decision-making skills. Moreover, focusing specifically on what clients are required to learn to improve their career problem-solving skills, counselors can look beyond the traditional one-on-one counseling relationship and creatively develop facilitative learning environments. Finally, assessing readiness for career problem solving enables counselors to match career service delivery resources to the depth and scope of the presenting problem, thereby fostering greater efficiency in the administration of career services.

The CIP model serves as a heuristic to enable individuals to systematically think through a career problem. By applying the model to solve a presenting problem, clients become better career problem solvers and decision makers, which in turn, can lead to satisfying, meaningful, and productive careers.

References:

- Hunt, E.B. (1971). What kind of computer is man? Cognitive Psychology, 2, 57-98.

- Lackman, R., Lackman, J. L., & Butterfield, E. C. (1979). Cognitive psychology and information processing. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem solving. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Peterson, G. W. (1998). Using the vocational card sort as an assessment of occupational knowledge. Journal of Career Assessment, 6, 49-67.

- Peterson, G. W., & Leasure, K. K. (2004, July). Problem mapping: The nexus of career and mental health counseling. Paper presented at the annual convention of the National Career Development Association, San Francisco, CA.

- Peterson, G. W., Sampson, J. P., Jr., Lenz, J. G., & Reardon, R. C. (2002). A cognitive information processing approach to career problem solving and decision making. In D. Brown (Ed.), Career choice and development (4th ed., pp. 312-369). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Peterson, G. W., Sampson, J. P., Jr., & Reardon, R. C. (1991). Career development and services: A cognitive approach. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Sampson, J. P., Jr., Peterson, G. W., Lenz, J. G., Reardon, R. C., & Saunders, D. E. (1996). The Career Thoughts Inventory (CTI). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Sampson, J.P., Jr., Peterson, G. W., Lenz, J. G., Reardon, R. C., & Saunders, D. E. (1996). Improving your career thoughts: A workbook for the Career Thoughts Inventory. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Sampson, J. P., Jr., Peterson, G. W., Reardon, R. C., & Lenz, J. G. (2000). Using readiness assessment to improve career services: A cognitive information processing approach. The Career Development Quarterly, 49, 146-174.

- Sampson, J. P., Jr., Reardon, R. C., Peterson, G. W., & Lenz, J. G. (2004). Career counseling and services: A cognitive information processing approach. Belmont, CA: Thomson.