Equity Theory Definition

Equity theory posits that when it comes to relationships, two concerns stand out: (1) How rewarding are their societal, family, and work relationships? (2) How fair and equitable are those relationships? According to equity theory, people feel most comfortable when they are getting exactly what they deserve from their relationships—no more and certainly no less. Equity theory consists of four propositions:

- Proposition I. Men and women are “wired up” to try to maximize pleasure and minimize pain.

- Proposition II. Society, however, has a vested interest in persuading people to behave fairly and equitably. Groups will generally reward members who treat others equitably and punish those who treat others inequitably.

- Proposition III. Given societal pressures, people are most comfortable when they perceive that they are getting roughly what they deserve from life and love. If people feel overbenefited, they may experience pity, guilt, and shame; if underbenefited, they may experience anger, sadness, and resentment.

- Proposition IV. People in inequitable relationships will attempt to reduce their distress via a variety of techniques: by restoring psychological equity, actual equity, or leaving the relationship.

Context and Importance of Equity Theory

People everywhere are concerned with justice. “What’s fair is fair!” “She deserves better.” “It’s just not right.” “He can’t get away with that: It’s illegal.” “It’s unethical!” “It’s immoral.” Yet, historically, societies have had very different visions as to what constitutes social justice and fairness. Some dominant views include the following:

- All men are created equal.

- The more you invest in a project, the more profit you deserve to reap (American capitalism).

- Each according to his need (Communism).

- Winner take all (dog-eat-dog capitalism).

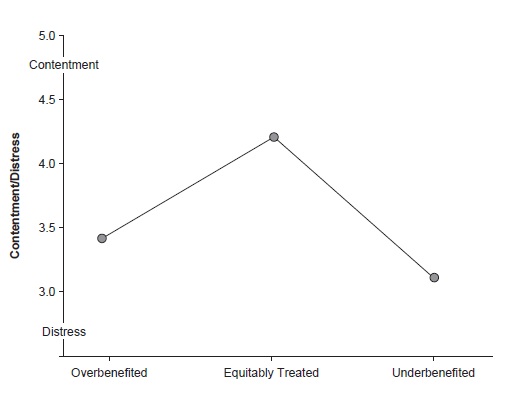

Figure 1: The Impact of Equity on Contentment With the Relationship

Nonetheless, in all societies, fairness and justice are deemed important. This entry will consider the consequences for men and women when they feel fairly or unfairly treated. Although equity has been found to be important in a wide variety of relationships— societal relationships, romantic and family relationships, helping relationships, exploitative relationships, and work relationships—this entry will focus on the research in one area: romantic and marital relationships.

Measuring Equity

Although (technically) equity is defined by a complex formula, in practice, in love relationships, equity has been assessed by a simple measure:

Considering what you put into your (dating relationship) (marriage), compared to what you get out of it… and what your partner puts in compared to what he or she gets out of it, how does your (dating relationship) (marriage) “stack up”?

- +3: I am getting a much better deal than my partner.

- +2: I am getting a somewhat better deal.

- +1: I am getting a slightly better deal.

- 0: We are both getting an equally good, or bad, deal.

- -1: My partner is getting a slightly better deal.

- -2: My partner is getting a somewhat better deal.

- -3: My partner is getting a much better deal than I am.

On the basis of their answers, persons can be classified as overbenefited (receiving more than they deserve), equitably treated, or underbenefited (receiving less than they deserve).

Equity in Love Relationships: The Research

There is considerable evidence that in love relationships, equity matters. Specifically, researchers find that the more socially desirable people are (the more attractive, personable, famous, rich, or considerate they are), the more socially desirable they will expect a mate to be. Also, dating couples are more likely to fall in love if they perceive their relationships to be equitable. Couples are likely to end up with someone fairly close to themselves in social desirability. They are also likely to be matched on the basis of self-esteem, looks, intelligence, education, mental and physical health (or disability). In addition, couples who perceive their relationships to be equitable are more likely to get involved sexually. For example, couples were asked how intimate their relationships were—whether they involved necking, petting, genital play, intercourse, cunnilingus, or fellatio. Couples in equitable relationships generally were having sexual relations. Couples in inequitable relationships tended to stop before going all the way. Couples were also asked why they’d made love. Those in equitable affairs were most likely to say that both of them wanted to have sex. Couples in inequitable relationships were less likely to claim that sex had been a mutual decision. Dating and married couples in equitable relationships also had more satisfying sexual lives than their peers. Equitable relationships are comfortable relationships. Researchers have interviewed dating couples, newlyweds, couples married for various lengths of time, including couples married 50+ years. Equitable relationships were found to be happier, most contented, and most comfortable at all ages and all stages of a relationship.

Equitable relationships are also stable relationships. Couples who feel equitably treated are most confident that they will still be together in 1 year, 5 years, and 10 years. In equitable relationships, partners are generally motivated to be faithful. The more cheated men and women feel in their marriages, the more likely they are to risk engaging in fleeting extramarital love affairs. Thus, people care about how rewarding their relationships are and how fair and equitable they seem to be.

Equity Theory Implications

Cross-cultural and historical researchers have long been interested in the impact of culture on perceptions of social justice. They contend that culture exerts a profound impact on how concerned men and women are with fairness and equity and on how fairness is defined, especially in the realm of gender relationships.

Cultural and historical perspectives suggest several questions for researchers interested in social justice: What aspects of justice, love, sex, and intimacy are universal? Which are social constructions? In the wake of globalization, is the world becoming one and homogeneous, or are traditional cultural practices more tenacious and impervious to deep transformation than some have supposed?

Theorists are also engaged in a debate as to whether certain visions of social justice, (especially in romantic and marital relationships) are better than others. Some cultural theorists argue that all visions are relative and that social psychologists must avoid cultural arrogance and ethnocentrism and strive to respect cultural variety. Others insist that universal human rights do exist and that certain practices are abhorrent, whatever their cultural sources. These include genocide (ethnic cleansing), torture, and in the area of gender and family relationships, the sale of brides, the forcing of girls into prostitution, dowry murders, suttee or widow burning, genital mutilation, infanticide, and discriminatory laws against women’s civic, social, and legal equality, just to name just a few. In this world, in which the yearning for modernity and globalization contend with yearnings for cultural traditions, this debate over what is meant by equity and social justice is likely to continue and to be a lively one.

References:

- Hatfield, E., Berscheid, E., & Walster, G. W. (1976). New directions in equity research. In L. Berkowitz & E. Hatfield (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 9, pp. 1-42). New York: Academic Press.

- Hatfield, E., Walster, G. W., & Berscheid, E. (1978). Equity: Theory and research. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.