Equity theory is a conceptualization that focuses on the causes and consequences of people’s perceptions of equity and inequity in their relationships with others. First proposed by J. Stacy Adams in 1963 and fully developed in a chapter published 2 years later, equity theory draws on earlier social psychological concepts inspired by Fritz Heider’s balance theory (e.g., relative deprivation, cognitive dissonance, and distributive justice). Although equity theory was developed as an approach to explaining the dynamics of social exchange relationships in general, it has been in the work context that the theory’s value was most strongly established.

Components of Equity Theory

According to equity theory, people make comparisons between themselves and certain referent others with respect to two key factors—inputs and outcomes.

- Inputs consist of those things a person perceives as contributing to his or her worth in a relationship. In a work setting, inputs are likely to consist of a person’s previous experience, knowledge, skills, seniority, and effort.

- Outcomes are the perceived receipts of an exchange relationship—that is, what the person believes to get out of it. On the job, primary outcomes are likely to be rewards such as one’s pay and fringe benefits, recognition, and the status accorded an individual by others.

It is important to note that the inputs and outcomes considered by equity theory are perceptual in nature. As such, they must be recognized by their possessor and considered relevant to the exchange.

The referent other whose outcomes and inputs are being judged may be either internal or external in nature. Internal comparisons include oneself at an earlier point in time or some accepted (i.e., internalized) standard. External comparisons involve other individuals, typically selected based on convenience or similarity. Equity theory is rather vague about the specific mechanisms through which referent others are chosen.

States of Equity and Inequity

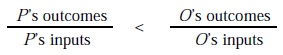

In the course of a social exchange with another, or when a person (P) and another (O) are corecipients in a direct exchange with a third party, P and O will compare their own and others’ inputs and outcomes. A state of equity is said to exist for P whenever he or she perceives that the ratio of his or her own outcomes to inputs is equal to the corresponding ratio of O s outcomes to inputs. Thus, a state of equity is said to exist for P when

Individuals experiencing states of equity in a relationship are said to feel satisfied with those relationships.

By contrast, a state of inequity is said to exist for P whenever he or she perceives that the ratio of his or her own outcomes to inputs and the ratio of O s outcomes to inputs are unequal. Inequitable states are purported to result in tension—known as inequity distress—and negative affective reactions. The degree of these adverse reactions is said to be proportional to the perceived magnitude of the inequity. Equity theory distinguishes between the following two types of inequitable states:

- Underpayment inequity is said to exist for P whenever his or her own outcome-input ratio is less than the corresponding outcome-input ratio of O—that is, when

States of underpayment inequity are claimed to result in feelings of anger in P.

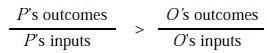

- Overpayment inequity is said to exist for P whenever his or her own outcome-input ratio is greater than the corresponding outcome-input ratio of O—that is, when

States of overpayment inequity are claimed to result in feelings of guilt in P.

Modes of Inequity Reduction

Because the emotional reactions to inequity—guilt and anger—are negative in nature, the individuals experiencing them are purported to be motivated to redress them. In other words, they will engage in effort to change unpleasant inequitable states, to more pleasant, equitable states—that is, to redress the inequity. Following from cognitive dissonance theory, Adams has proposed six different modes of inequity reduction, described in the following paragraphs.

Altering One’s Own Inputs

If P feels overpaid, he or she may raise his or her own inputs in an effort to bring his or her outcome-input ratio into line with Os. P may do this by working longer hours (assuming that P is a salaried, rather than an hourly paid, employee), by putting forth more effort, and/or by doing work of higher quantity or quality, for example. By contrast, if P feels underpaid, he or she may lower his or her own inputs in an effort to match O’s outcome-input ratio. P may do this by reducing the amount of effort put forth, by working fewer hours (again, assuming that P is a salaried employee), and/or by doing work of lower quantity or quality.

Altering One’s Own Outcomes

In addition to adjusting one’s own inputs (i.e., the numerator of the equity equation), P also may adjust his or her own outcomes (i.e., the denominator of the equity equation). If P feels overpaid, he or she may lower his or her own outcomes in an effort to bring his or her outcome-input ratio into line with O’s. P may do this by not accepting a raise or by forsaking an opportunity to move to a larger, more prestigious office, for example. By contrast, if P feels underpaid, he or she may attempt to raise his or her own outcomes in an effort to match O’s outcome-input ratio. P may do this, for example, by seeking and receiving a raise, and/or by taking home company property in an effort to receive a larger share of outcomes withheld.

Cognitively Distorting One’s Own Outcomes or Inputs

In addition to making behavioral changes, states of inequity motivate people to cognitively distort their perceptions of their own outcomes or inputs to perceive that conditions are equitable. For example, an under-paid person may come to believe that his or her work contributions are really not as great as previously believed (e.g., he or she is not as well qualified as P) or that he or she is more highly compensated than previously considered (e.g., he or she works fewer hours than P but is equally paid). Correspondingly, an overpaid person may come to believe that his or her work contributions, in reality, are greater than previously believed (e.g., he or she has more experience than P)or that he or she is not really any more highly compensated than P (e.g., he or she works more hours than the equally paid P).

Leaving the Field

As an extreme measure, one may redress inequity by terminating the inequitable relationship altogether. On the job, this termination may take such forms as seeking other positions within one’s existing organization or resigning from that organization entirely. Ending the social exchange functions instrumentally by rendering the social comparison process moot and symbolically by signaling the extent of one’s disaffection. Because of its extreme nature, this measure typically occurs only after other modes of inequity reduction have been attempted unsuccessfully.

Acting on the Object of Comparison by Behaviorally Altering or Cognitively Distorting the Other’s Outcomes or Inputs

Just as people perceiving that they are in inequitable relationships may change their own outcomes or inputs behaviorally or cognitively, they also may attempt to alter or cognitively distort the outcomes or inputs of others. For example, P may focus on O’s outcomes behaviorally by encouraging O to ask for a raise (if P feels overpaid) or to not accept a bonus (if P feels underpaid), or psychologically, by perceiving that O is, in reality, more highly paid than previously believed (if P feels overpaid) or that O is not actually as highly paid as previously believed (if P feels underpaid). Analogously, P may focus on O’s inputs behaviorally by encouraging O to work fewer hours (if P feels overpaid) or to work more hours (if P feels underpaid), or psychologically by perceiving that O is, in reality, not working as hard as previously believed (if P feels overpaid) or that O actually is working much harder than previously believed (if P feels underpaid).

Changing the Basis of Comparison

According to equity theory, feelings of equity or inequity are based on the specific referent comparisons made. Thus, it is possible for people to feel overpaid relative to some individuals, underpaid relative to others, and equitably paid relative to still another group. For example, a management professor may feel overpaid relative to philosophy professors and underpaid relative to law professors, but equitably paid relative to other management professors. Simply by switching one’s basis of comparison, it is possible for individuals who feel overpaid or underpaid to feel more equitably paid. This underscores the fundamentally perceptual, and not necessarily objective, nature of perceptions of equity and inequity.

Equity theory offers little insight into how people come to select particular inequity reduction mechanisms. It is noted, however, that people favor the least effortful alternatives, thereby making cognitive modes of inequity reduction preferable to behavioral ones. The most extreme reaction, leaving the field, is least preferable.

Research Assessing Equity Theory

The earliest tests of equity theory were laboratory experiments in which participants were led to believe that they were inequitably overpaid or underpaid for performing a task (e.g., they were paid more than or less than expected). The dependent measure was the degree to which participants adjusted their work performance, raising or lowering their inputs, relative to members of control groups who were equitably paid. Such efforts generally supported equity theory. The most compelling evidence came from tests of overpayment inequity, in which it was found that people who were paid more than expected raised their inputs, producing more work than equitably paid participants. Additional research established not only that people respond to inequities as predicted by equity theory, but that they also proactively attempt to create equitable states by allocating rewards to others in proportion to their contributions.

The most recent research inspired by equity theory has been broader in scope and more naturalistic in methodology. Such efforts have found that employees respond to inequities caused by such status-based outcomes as job title and office design by adjusting their performance accordingly. Current research also reveals that employees sometimes steal property from their companies in response to underpayment inequity. In so doing, employees are not only modeling the deviant behavior of their organizations (i.e., stealing in response to underpaying them) but also attempting to even the score by compensating themselves (i.e., raising their outcomes) for payment denied.

The Current Status of Equity Theory

In the 1980s, organizational scholars recognized that equity theory’s conceptualization of fairness in organizations was highly limiting because it focused only on the distribution of outcomes. This disenchantment led industrial and organizational psychologists to follow the lead of social psychologists by broadening their efforts to understand fairness in organizations by focusing on procedural justice. As a result, equity theory is no longer the dominant approach to understanding fairness in the workplace. Instead, it is acknowledged to be only one conceptualization within the broader domain of organizational justice.

References:

- Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances In experimental social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 267-299). New York: Academic Press.

- Adams, J. S., & Freedman, S. (1976). Equity theory revisited: Comments and annotated bibliography. In L. Berkowitz & E. Walster (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 9, pp. 43-90). New York: Academic Press.

- Greenberg, J. (1982). Approaching equity and avoiding inequity in groups and organizations. In J. Greenberg & R. L. Cohen (Eds.), Equity and justice in social behavior (pp. 389-435). New York: Academic Press.

- Greenberg, J. (1987). A taxonomy of organizational justice theories. Academy of Management Review, 12, 9-22.

- Greenberg, J. (1990). Employee theft as a reaction to underpayment inequity: The hidden cost of pay cuts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 561-568.

- Greenberg, J. (1996). The quest for justice on the job. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Leventhal, G. S. (1976). The distribution of rewards and resources in groups and organizations. In L. Berkowitz & W. Walster (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology(Vol. 9, pp. 91-131). New York: Academic Press.

- Leventhal, G. S. (1980). What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In K. Gergen, M. Greenberg, and R. Willis (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 27-55). New York: Plenum Press.

- Mowday, R. T., & Colwell, K. A. (2003). Employee reactions to unfair outcomes in the workplace: The contributions of equity theory to understanding work motivation. In L. W. Porter, G. A. Bigley, & R. M. Steers (Eds.), Motivation and work behavior (pp. 65-113). Burr Ridge, IL: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.