Why do some individuals participate intensely in sport activities over many years while others never get actively involved in sport or exercise? What influences initial participation in sport or exercise? What influences continued participation? What influences the intensity of participation?

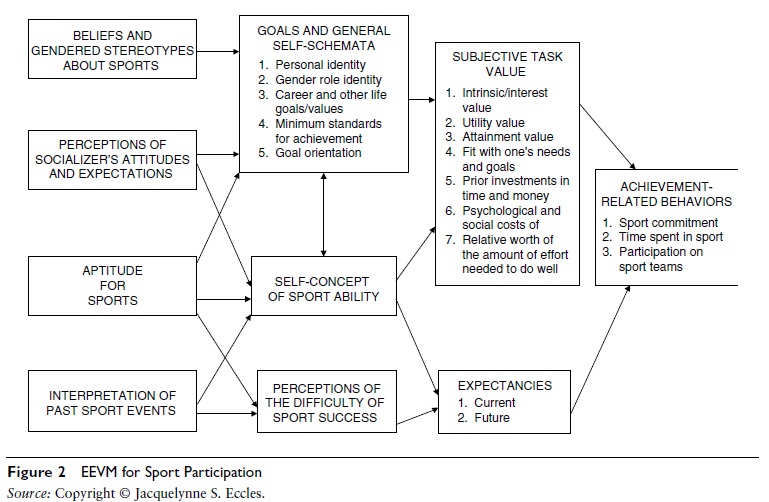

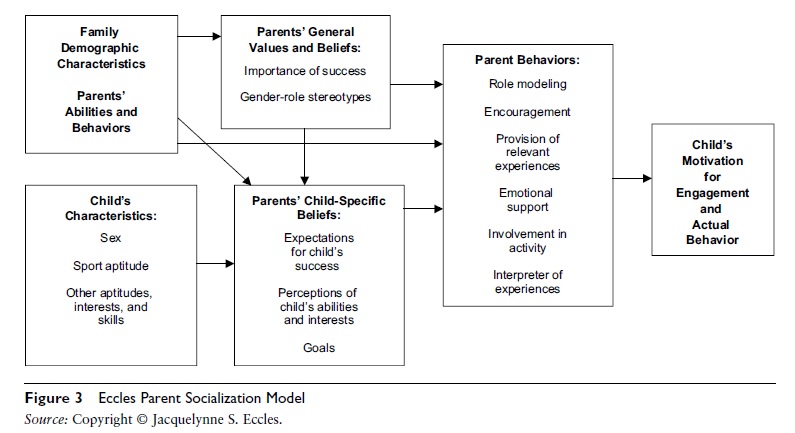

How do we explain drop-out from sport and exercise engagement? How do we explain both individual and group differences in sport and exercise engagement? Questions such as these have driven work in the area of motivation and sport and exercise for at least the last 50 years. Two main theoretical perspectives have emerged to address these types of questions: expectancy-value theory and self-determination theory. This entry focuses on one particular version of expectancy-value theory: Eccles and colleagues’ Expectancy-Value Theory of Achievement-Related Behavioral Choices. This theoretical model has two components: a psychological component, illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, and a socialization component, illustrated in Figure 3. The following sections provide a brief description of each of these components and a summary of related empirical research.

Psychological Influences on Sport and Exercise Participation

Building on the work of Norman T. Feather, Victor Vroom, Albert Bandura, and John W. Atkinson, Jacquelynne Eccles and colleagues developed a comprehensive theoretical model of achievement-related choices, first published in 1983 (see Figure 1) and first directly applied to sport by Eccles and Rena D. Harold in 1991. It is henceforth referred to as the Eccles Expectancy-Value Model (EEVM). Eccles and colleagues hypothesized that both individual and group, for example gender or race or ethnic group, differences would be most directly influenced by individuals’ expectations for success and the relative importance or value individuals attached to sport or exercise activities compared to other activity options (see Figure 2). They then hypothesized how these quite domain specific self and task-related beliefs are influenced by cultural norms and stereotypes, experiences, aptitudes, and more general personal beliefs. In 1993, they specified a model of parental influences on the development of the psychological components of EEVT (see Figure 3).

Figure 1 General Eccles Expectancy-Value Model of Activity Choices

According to the EEVM, people will be most likely to participate in those activities that they think they can master and that have high subjective task value for them. Expectations for success (domain-specific beliefs about one’s personal efficacy to master the task), in turn, depend on both the confidence that individuals have in their various abilities and the individuals’ estimations of the difficulty of the various options they are considering.

Eccles and associates also predicted that these self and task-related beliefs were shaped over time both by experiences with the related activities, and by individuals’ subjective interpretation of these experiences. For example, does the individual think that personal prior and current successes reflect high ability or lots of hard work? And if the latter, will it take even more work to continue to be successful? Conversely do personal failures or difficulties reflect lack of natural talent or deficits in current abilities? Can the current ability level be changed through practice and instruction or does it reflect a stable entity linked to genetic or other stable biological influences—that is does it reflect natural talents? Are these natural talents believed to be linked to gender or other group characteristics? The latter interpretative questions are particularly important for explaining gender and other group differences in participation in sports and exercise. It is likely, for example, that females in many cultures receive less support for developing a strong sense of their talent for sport from their parents, teachers, and peers than males and are more likely to attribute their difficulties in mastering sports to insufficient natural talent than males. Research has supported this prediction.

Likewise, the EEVM model specifies that the subjective task value of various activities is influenced by several factors. For example, how much does the person enjoy doing sport compared to other activities (referred to as intrinsic interest in the model)? Is participation in sport or exercise seen as instrumental in meeting the individual’s long or short-range goals (referred to as utility value)? Is being good at sport or exercise a critical part of the individual’s identity (referred to as attainment value)? Does participating in sport or exercise interfere with other more valued options because of the amount of work needed to be successful either in the major or in the future professions linked to the major (referred to as cost)? The answers to these kinds of questions have proved critical for explaining both individual and groups differences in sport and exercise participation.

Figure 2 EEVM for Sport Participation Source: Copyright © Jacquelynne S. Eccles

As the model was developed in the mid-1970s, it was clear that the theoretical grounding for understanding the nature of subjective task value was much less well developed than the theoretical grounding for understanding the nature of expectations for success. Consequently, Eccles and associates elaborated their notion of subjective task value to help fill this void. Drawing upon work associated with achievement motivation, intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation, self-psychology, identity formation, economics, and organization psychology, they hypothesized that subjective task value was composed of at least four components:

- Interest value (the enjoyment one gets from engaging in the task or activity)

- Utility value (the instrumental value of the task or activity for helping fulfill another shortor long-range goal)

- Attainment value (the link between the task and one’s sense of self and identity

- Cost (defined in terms of either what may be given up by making a specific choice or the negative experiences associated with a particular choice)

It is the belief of Eccles and colleagues that the last three of these are particularly relevant for understanding gender and other group differences in activity choices. By and large, research has supported these predictions.

Furthermore, Eccles and colleagues believe that both individual and group differences in these aspects of subjective task value are heavily influenced by social forces and socialization, which themselves are influenced by cultural norms and stereotypes. For example, have the individual’s parents, counselors, friends, or romantic partners encouraged or discouraged the individual from participating in sport or exercise? More specifically with regard to gender, for example, Eccles and colleagues argued that the socialization processes linked to gender roles are likely to influence both short and long-term goals and the characteristics and values most closely linked to core identities. They predicted that males would receive more support for developing a strong interest in sport from their parents, teachers, and peers than females; research has supported this prediction. For example, gender-role socialization has been shown to lead to gender differences in adolescents’ sport ability self-concepts, the subjective task value of sport, and actual engagement in sport activities. These outcomes, in turn, have been shown to predict adult involvement in sport and exercise activities.

Figure 3 Eccles Parent Socialization Model

In summary, Eccles and colleagues assume that activity choices, such as participating in sport and exercise, are guided by (a) individuals’ expectations for success (sense of personal efficacy) regarding the various options, as well as their sense of competence for various tasks; (b) the relation of the options to their short and long-range goals, to their core personal and social identities, and to their basic psychological needs; (c) individuals’ culturally-based role schemas linked to gender, social class, and ethnic group; and (d) the potential cost of investing time in one activity rather than another. They further assume that all of these psychological variables are influenced by individuals’ histories as mediated by their interpretation of these experiences, by cultural norms, and by the behaviors and goals of one’s socializers and peers.

Eccles and her associates have spent the last 40 years amassing evidence to support each of these hypotheses. The findings related to gender differences participation in sport and exercise are quite robust. Here are just a few examples of both the psychological and socialization models. (All of the survey instruments, details on the studies, and the publications themselves are available at www.rcgd.isr.umich.edu/garp.)

First, the researchers looked at the psychological predictors of participation in sport in high school. They used path analysis to determine whether the gender difference in sport participation was mediated by constructs directly linked to expectations for success (specifically the students’ self-concept of their sport ability) and subjective task value (specifically, how much they enjoyed sport), the subjective importance of doing well in sport, and the usefulness of sport while controlling for the students’ scores on. As predicted, the gender difference in participating in sport was mediated by the gender differences in these beliefs.

The second part of the research has focused on the role of experiences in the home in shaping both individual and group differences in the self and task-related beliefs just discussed, as well as such differences in sport and exercise participation. First, using a variety of longitudinal modeling techniques, Eccles and colleagues were able to confirm most of the basic links summarized in Figure 3. Many parents do endorse gender stereotypic beliefs about general gender differences in abilities and interest in many and parents’ gender-role stereotypes predict their perceptions of their own children’s math, sport, and English abilities and interests even after independent assessments of their children’s actual abilities in these three domains have been controlled, leading them on average to underestimate their daughters’ athletic abilities. In turn, parents’ estimates of their children’s abilities in different skills predict developmental changes in their children’s own estimates of their abilities in these skills, as well as the children’s expectations for success in these different skill areas, leading to the kinds of gender differences in the children’s own beliefs and task values discussed earlier.

Second, on average, parents provide their daughters and sons with gender-role stereotypic types of toys and activity opportunities, particularly in relation to sport. Not surprisingly, these differential patterns of experiences partially mediate the emergence of gender differences in children’s confidence in their own abilities, their interests in participating in different activities, particularly, and their actual emerging competencies Not surprisingly, the extent to which each of these facts holds true is more marked when parents endorse the traditional gender-role stereotypes associated with both ability and interest in these different skills areas.

Conclusion

Research conducted over the past 4 decades by Eccles and colleagues, and by other researchers as well, has provided clear evidence that gender-role related personal and social processes explain, at least in part, the gender differences we see in sport participation. Much less work has been done on exercise. Furthermore, interventions have been created that can help ameliorate these processes, with the result that both girls and women and boys and men are able to make less gender-role stereotypic choices for their own lives.

References:

- Eccles, J. S. (1987). Gender roles and women’s achievement-related decisions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 11, 135–172.

- Eccles, J. S. (1993). School and family effects on the ontogeny of children’s interests, self-perceptions, and activity choice. In J. Jacobs (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1992: Developmental perspectives on motivation (pp. 145–208). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Eccles, J. S. (2006). Families, schools, and developing achievement-related motivations and engagement. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (pp. 665–691). New York: Guilford Press.

- Eccles, J. S., Jacobs, J. E., & Harold, R. D. (1990). Gender-role stereotypes, expectancy effects, and parents’ socialization of gender differences. Journal of Social Issues, 46, 183–201.

- Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2004). Parental influences on youth involvement in sports. In M. Weiss (Ed.), Developmental sport and exercise psychology: A lifespan perspective (pp. 145–164). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2005). Family socialization, gender, and sport motivation and involvement. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 27, 3–31.

- Jacobs, J. E., & Eccles, J. S. (1992). The impact of mothers’ gender-role stereotypic beliefs on mothers’ and children’s ability perceptions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 932–944.

- Jacobs, J. E., Vernon, M. K., & Eccles, J. S. (2005). Activity choices in middle childhood: The roles of gender, self-beliefs, and parents’ influence. In J. L. Mahoney, R. W. Larson, & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Organized activities as contexts of development: Extracurricular activities, after-school and community programs (pp. 235–254). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Perkins, D. F., Jacobs, J. E., Barber, B., & Eccles, J. S. (2004). Childhood and adolescent sports participation as predictors of participation in sports and physical fitness activities during adulthood. Youth and Society, 35, 495–520.

- Rodriguez, D., Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2003). Changing competence perceptions, changing values: Implications for youth sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 15(1), 67–81.

See also:

- Sports Psychology

- Sport Motivation