Fear of crime is an important strand of criminal psychology that has garnered much attention since the mid-20th century. However, fear of crime has yet to have a universally accepted definition, and as the focus of policing turns increasingly to cybercrime, the concept potentially needs revisiting once again. According to Chris Hale, at its most basic level, the fear of crime refers to the fear of being a victim of crime rather than the fear of crime itself (or the probability of being a victim of a crime). Several definitions have been put forward: John E. Conklin defines it in terms of a sense of personal security in the community, whereas Jeanette Covington and Ralph B. Taylor defines it more in terms of the emotional response to a violent crime and physical harm. Other definitions have suggested that the fear of crime is an emotional response of dread or anxiety to crime or symbols that a person associates with crime.

Research suggests that high levels of fear affect society and individuals in a variety of ways. On an individual level, those who report high levels of fear of crime are more likely to report poor health and a lower quality of life, while communities that are disproportionately more likely to feel unsafe when out after dark also express lower levels of trust and are less likely to think their neighbors are friendly. The causal relationship between these perceptions is not clear, but measures of fear of crime are typically indicators of some level of social harm.

How Is Fear of Crime Measured?

The measurement of fear of crime is as contested as the concept itself. Historically, the measurement has relied on survey data, but a number of studies have sought to validate this and develop new ways of understanding public perceptions.

Perception of safety questions—such as “How safe do you feel walking alone in this area after dark?”—has received criticism and has been shown to display mismatches, whereby it was clear that quantitative and qualitative research methodologies do not produce the same findings. Other measures have become standard and validated, such as asking participants to summarize their levels of worry about specific crimes and the likelihood of becoming a victim.

However, long-standing fear of crime measures have begun to take a back seat to measures—and accompanying initiatives—focused more on public confidence in law agencies. For instance, in the United Kingdom, in response to 10 years of statistics demonstrating significant decreases in crime rates but without any accompanying shifts in public perceptions of levels of crime, a single measure of police performance was introduced in 2009 to evaluate the impact of crime policy, based on a survey measure of public confidence in policing. Public perceptions were prioritized ahead of recorded crime and detection rates, the rationale being that if the rate of crime falls, but people do not have the confidence that this is happening in their neighborhood, then their quality of life will continue to be affected and the benefits of reduced crime would not be realized. This matters because it undermines the police and government efforts to engage the community through crime reporting, intelligence gathering, and community engagement activities. This single measure was subsequently replaced in the United Kingdom by greater devolution of powers and introduction of police and crime commissioners to represent and foster public confidence in policing.

While confidence measures have taken center stage, the longer standing fear of crime measures continue to be asked in the Crime Survey of England and Wales (CSEW; formerly the British Crime Survey). In 2013/14, CSEW found that 19% of adults thought that it was either very or fairly likely that they would be a victim of crime within the next 12 months. One in seven adults (12%) were classified as having a high level of fear about violent crime, 11% about burglary, and 7% about car crime.

All of these measures were at a similar level to the 2012/13 survey, and the general trend has been flat for a number of years. This is in contrast to actual crime levels, which have, broadly, declined in the United Kingdom for a number of years, although this is not universal across crime categories. The latest release of the CSEW has shown a 7% decrease in incidents but increases in some of the lower volume but more serious types of police-recorded violence.

Despite this complexity, it still seems clear that there is a long-term gap between trends in the likelihood of being a victim of crime and the perceived likelihood of being a victim of crime or broader measures of fear of crime. This phenomenon is not unique to the United Kingdom, and the United States has seen a sharp decline in violent crime rate since the mid-1990s, but a 2011 Gallup Poll found that the majority of Americans continue to believe that the nation’s crime problem is getting worse. Across Europe, this phenomenon has also been observed; fear of crime has increased slowly but steadily across the European Union as a whole between 1996 and 2002 (with the only member state where there has been a continuous decline since 1996 in the feeling of insecurity is Germany), while crime trends decreased.

Why Do These Perception Gaps Exist?

It seems highly likely that the media have a significant influence on the public’s views. The CSEW 2013/14 found that among adults the most cited source of knowledge about levels of crime in the country was news programs on television or radio (67%). Other common sources mentioned were word of mouth or information from other people (32%) and newspapers (tabloid, 31%; local, 31%). Sources of information are important in determining how the influence will sway public opinion for instance; one study by Paul Williams and Julie Dickinson found that 65% of newspaper crime reporting involved violent crime, despite these types of crime making up only 6% of recorded crime. Chris Greer found that all media tend to exaggerate the extent of violent crime while also suggesting that different types of crime and victims derive different newsworthiness, leading in some cases to long-term collective moral outrage and media campaigns instilling in the public psyche the prevalence of serious violent crime.

This relates to another reason suggested for the perception gap; there are a number of high-profile or signal crimes that have a greater impact on perceptions than other crimes, and these signal crimes—in contrast to some other crimes—are not decreasing in the numbers reported. There is some evidence for this. For example, according to the Home Office, the number of homicides in England and Wales rose from 71 to 574 between September 2014 and September 2015—an increase of 14%, fueled by rises in knife and gun crime.

What Drives Public Perceptions of Crime?

Looking across a number of studies, there are several common factors associated with fear of crime at individual and societal levels. First, there are significant demographic variations in perceptions of the fear of crime. Gender is one of the most consistent predictors of differences in the reported level of fear of crime. In nearly 50 years of research in the fear of crime, the distribution in the population, and its determinants, virtually all studies that integrated sex as an independent variable have found significantly higher levels of fear that are reported by women than by men.

In 2015, the UK Office for National Statistics also found that women were more likely than men to have believed that crime had risen in recent years. This was true for crime across the United Kingdom both as a whole (68% and 55%, respectively) and locally (36% and 28%, respectively). A broader conceptualization of worry might partially explain why women had a higher level of worry about being a victim of violent crime compared with men (18% compared with 6%). The pattern was similar for fear of being burgled with 14% of women having a high level of worry compared with only 8% of men.

There is also a relationship between age and fear of crime. Evidence suggests that those aged between 45 and 64 years were generally more worried about crime than other age-groups, aside from the exception of fear about violent crime, where those in the youngest age-group (16–24) had the highest level of worry (see Figure 1).

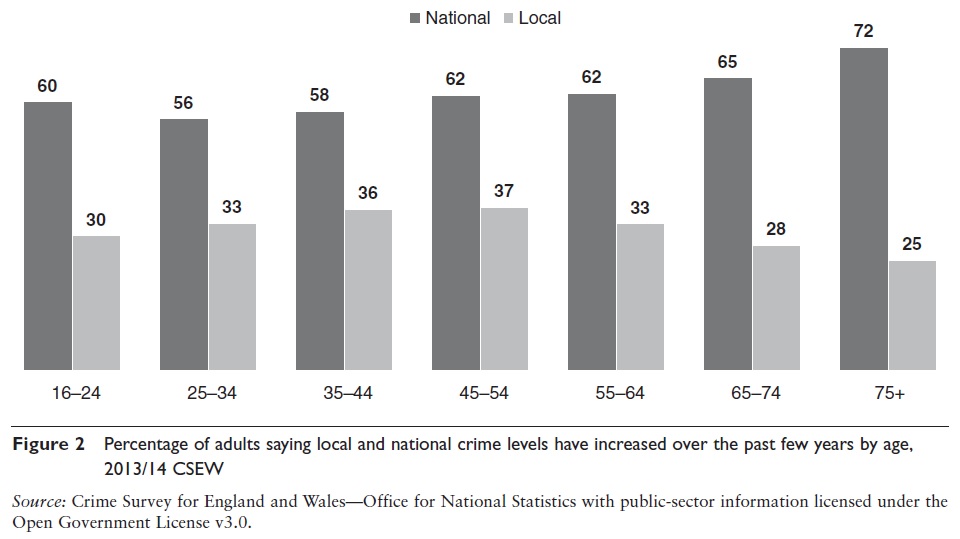

With regard to the national picture in the United Kingdom, the general pattern was for perceptions of crime rising in line with age, as shown in Figure 2; those aged 75 and over were most likely to view it as having risen in recent years (72%). Perceptions of crime rising locally peaked in the 35–44 and 45–54 age-groups (36% and 37%, respectively) and then reduced with increasing age. Those aged 75 and over were the most likely to think crime was rising across the country as a whole, and they were the least likely to view local crime as having risen (25%).

Therefore, variation between groups may reflect differences in perceived vulnerability rather than the perceived risk of falling victim, as it has been claimed that responses about worry are driven by feelings of vulnerability and factors associated with it. For instance, Pamela Wilcox Rountree and Kenneth C. Land have suggested that responses may encompass more than just worry about the crime being committed but also include concerns about the ramifications of different crime types and the perceived victimization that may occur. In addition, Helmut Hirtenlehner and Stephen Farrall argued that women have a higher fear of certain crime types compared with men due to their elevated fear and risk of sexual assault.

Another possible explanation for the mismatch between actual trends and perceptions is that the definition of crime in the public’s mind incorporates far wider issues than official definitions of crime, with personal conceptions of crime potentially encompassing such things as terrorism and antisocial behavior (ASB). There is qualitative and survey evidence that suggests that this is the case, and so to the extent that these have become greater concerns since the late 1990s (which is certainly the case for terrorism and possibly the case for ASB, depending on the measure used), then crime will also be seen to have increased. Perceptions of ASB and terrorism also seem to drive confidence in the government’s handling of crime. ASB is a particularly important driver, with studies showing that disorder in a respondent’s local area directly increases his or her view that overall local crime is rising. With terrorism, the evidence is less clear-cut, but it is thought of as an important crime issue by some, and concern about terrorism has increased substantially since the late 1990s.

Perhaps a more significant factor that is yet to be factored into relevant measures or the understanding of fear of crime is the ever-increasing influence of cybercrime. The Internet provides not only new means of committing established crimes but also opportunities to undertake new types of crime, and there have been concerns that data collection, public understanding, and enforcement definitions have failed to keep up with the changing nature of crime. The extent of this issue in the United Kingdom, for example, was highlighted in CSEW for year ending June 2015, the first to include cybercrime as a crime type, whereby a 107% increase in crime was recorded, with 5.1 million estimated cybercrimes and frauds plus 2.5 million offenses under the Computer Misuse Act—hacking, identity theft, and malware. Revisiting the conceptual understanding of the public’s fear of crime to reflect the shifting nature of crime patterns and the associated shifts in people’s experiences of crime and their interactions with law enforcement agencies will be essential to ensure that fear of crime measures retain relevance.

References:

- Beatty, C., Grimsley, M., Lawless, P., & Wilson, I. (2005). New deal for communities national evaluation. Fear of crime in NDC areas: How do perceptions relate to reality? Sheffield, UK: Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University.

- Conklin, J. E. (1971). Dimensions of community response to the crime problem. Social Problems, 18(3), 373–385.

- Covington, J., & Taylor, R. B. (1991). Fear of crime in urban residential neighborhoods: Implications of between- and within-neighborhood sources for current models. Sociological Quarterly, 32(2), 231–249.

- Davies, P., Francis, P., & Greer, C. (2007). Victims, crime and society. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Duffy, B., Wake, R., Burrows, T., & Bremner, P. (2008). Closing the gaps—Crime and public perceptions. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 22(1–2), 17–44.

- Farrall, S., Bannister, J., Ditton, J., & Gilchrist, E. (1997). Questioning the measurement of the “fear of crime”: Findings from a major methodological study. British Journal of Criminology, 37(4), 658–679.

- Greer, C. (2005). Crime and media: Understanding the connections. In C. Hale, K. Hayward, A. Wahadin, & E. Wincup (Eds.), Criminology (pp. 177–203). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Hale, C. (1996). Fear of crime: A review of the literature. International Review of Victimology, 4, 79–150.

- Heath, L., Kavanagh, J., & Raethompson, S. (2001). Perceived vulnerability and fear of crime. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 33(2), 1–14.

- Hirtenlehner, H., & Farrall, S. (2014). Is the “shadow of sexual assault” responsible for women’s higher fear of burglary? The British Journal of Criminology, 54(6), 1167–1185.

- Ipsos MORI. (2016). Economist/Ipsos MORI February 2016 Issues index. Ipsos MORI, London, England. https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/economist-ipsos-mori-february-2016-issues-index

- Jackson, J. (2005). Validating new measures of the fear of crime. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(4), 297–315.

- LaGrange, R. L., Ferraro, K. F., & Supancic, M. (1992). Perceived risk and fear of crime: Role of social and physical incivilities. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 29, 3, 311–334.

- Office for National Statistics. (2008). From the neighbourhood to the national: Policing our communities together. London, UK: TSO.

- Office for National Statistics. (2015, March). Crime survey for England and Wales 2013/14 Public Perceptions of Crime. Newport, UK: Office for National Statistics.

- Office for National Statistics. (2015). Extending the crime survey for England and Wales (CSEW) to include fraud and cybercrime. Newport, UK: Office for National Statistics.

- Office for National Statistics. (2016, January). Crime in England and Wales: Year ending June 2015. Statistical Bulletin. Newport, UK: Office for National Statistics.

- Office for National Statistics. (2016, January). Crime in England and Wales: Year ending September 2015. Statistical Bulletin. Newport, UK: Office for National Statistics.

- Rix, A., Joshua, F., Maguire, M., Morton, S. (2009). Improving public confidence in the police: A review of the evidence. London, UK: Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate.

- Rountree, P. W., & Land, K. C. (1996). Perceived risk versus fear of crime: Empirical evidence of conceptually distinct reactions in survey data. Social Forces, 74(4), 1353–1376.

- Saad, L. (2011). Most Americans believe crime in U.S. is worsening. Gallup, Inc. Retrieved from gallup.com

- Sutton, R. M. (2004). Gender, socially desirable responding and the fear of crime: Are women really more anxious about crime? British Journal of Criminology, 45(2), 212–224.

- Williams, P., & Julie, D. (1993). Fear of crime: Read all about it? The relationship between newspaper crime reporting and fear of crime. The British Journal of Criminology, 33(1), 33–56.