Learning is a relatively permanent change in behavior due to experience. As the individual interacts with the environment, certain events promote behavior.

In some cases, the outcomes produced by those responses inform the individual about likely consequences for behavior in future situations. Behaviors include a wide array of events, from basic physical processes to complex higher-order cognitive functions. Thus, behavior is anything the individual does. Given sufficient information about the experience of the individual, predictions can be made about likely behaviors in future settings.

The contribution of biology is unique for each individual and lays the foundation for characteristic interactions with the environment. The particular repertoires of behavior, reflexes, and species-specific patterns of responding that are inherited within a group or organisms are referred to as learned, though at the level of phylogeny. In contrast, learning that occurs within the lifetime of a given organism is called ontogenetic.

In these interactions, learning can be affected by two general processes. Learning, or conditioning, that occurs in the lifetime of the individual can be produced through association of events or through the arrangement of consequences. Respondent conditioning is the process by which responses are elicited by stimuli that come to control behavior through their relationship with other known events. In contrast, operant conditioning is the process by which the likelihood of behavior is changed by the consequences that follow it in particular settings.

Learning can be the product of naturally occurring environmental relations or through intentionally arranged contingencies. When learning occurs through the use of programmed contingencies, an effort should be made to transfer stimulus control to naturally occurring contingencies to promote generalization and maintenance.

Respondent Conditioning

Respondent conditioning has also been known by other names. Frequently, it is referred to as Pavlovian conditioning because of Ivan Pavlov’s famous research with the learned salivation of dogs. Additionally, it came to be described as classical conditioning to distinguish it from operant conditioning in both entry into the scientific vocabulary of psychology and in how behavior is produced. Both terms, classical and Pavlovian, however, neglect the importance of the automatic nature of responses in the presence of certain stimulus events.

Figure 1 The Respondent Conditioning Model

Referring to Figure 1, you will see the three-step process involved in respondent conditioning. First, an unconditioned stimulus elicits an unconditioned response. Innate patterns of responding to particular events that occur involuntarily are referred to as reflexes. Responses that are present at birth, such as reflexes, are described as unconditioned. Unconditioned responses are behaviors that occur because of the action of unconditioned stimuli. Stimuli are described as persons, objects, or events in the environment that affect behavior. In respondent conditioning, stimuli are said to elicit responding because of automatic or innate behavioral patterns. Elicitation is the process whereby a stimulus has the power to cause a response. Think of the image of a rock flying toward the windshield of your car. You are aware that the windshield will protect you from the rock, but as it hits, you startle and blink anyway. In this case, we would say that the rock elicited, or brought forth, your startle response. It caused you to blink, you did not choose it voluntarily. In fact, you may have had difficulty preventing or minimizing the response because of its automatic or unconditioned nature.

The power that the stimulus has to cause a response in respondent conditioning is great; thus, we say that the stimulus has strong control over responding. Other stimuli may have differing degrees of control. The concept of stimulus control simply refers to how likely a given stimulus is to cause a particular response. Stimulus control is also a factor in how long a given unit of learning is maintained and how readily it is generalized.

The second step of respondent conditioning involves the pairing of a neutral stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus to elicit the unconditioned response. In addition to reflexes present at birth, new stimulus events that have no previous significance to the individual can also come to control, or elicit, previously known responses through the pairing of these new, or neutral, stimuli with unconditioned, or known, stimuli. Such pairing typically requires many practice trials. However, one trial learning can occur if the association between the neutral stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus is sufficiently strong. The frequency of pairing, saliency of the stimuli, timing of the stimulus presentation, and intensity of stimuli effect how quickly stimulus control will transfer from the unconditioned stimulus to the neutral stimulus to form the conditioned stimulus. It is also important to note that the order of stimulus presentation affects the learner’s ability to form associations. Presenting the unconditioned stimulus before the neutral stimulus is called backward conditioning, and it is rarely effective at transferring stimulus control from the unconditioned stimulus to the neutral stimulus. Instead, short delays between the presentation of the neutral stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus, or overlapping presentations produce the strongest associations between the two stimuli. It is this association that allows stimulus control to transfer from the unconditioned stimulus to the neutral stimulus.

After a transfer of stimulus control from the unconditioned stimulus to the neutral stimulus has occurred, the neutral stimulus is renamed the conditioned stimulus because it will now have the power to elicit the response independently. In the final phase of the conditioning event, we also rename the response, calling it now the conditioned response to indicate that it is elicited by the conditioned stimulus. Note that even though seven terms are present in the respondent conditioning event, there are really only two stimuli (one known and one novel) and a single response. The different names for terms at each step indicate the source of control over behavior.

The initial associations established through relationships with reflexes are called first-order conditioning. There are many stimuli that elicit responses automatically. For example, think of how you react to a loud noise in a quiet room or a warm cup of soup on a cold day. Stimuli that impact our senses directly are best considered in first-order conditioning events, such as sights, sounds, smells, physical sensations, and tastes. Others may pose that certain social stimuli as smiles or hugs can be included here as well. More complex patterns of responding can also be established through the association of conditioned stimuli with additional neutral stimuli, producing further conditioned responses. This process is referred to as higher-order, or second-order, conditioning because both stimuli are conditioned. Through higher-order conditioning, treatments such as systematic desensitization can establish new respondent associations to reverse the effects of such reflexive responding as that seen in phobias.

To determine whether a stimulus is unconditioned or conditioned, one can consider how an adult and a young infant may respond to it. If they respond the same, as in the case of a loud sound in a quiet room, then it is unconditioned. If their responses are different, as would be the case in presenting a $100 bill to the adult and the infant, then the different response must be the product of ontogenetic learning occurring during the lifetime of the individual, and thus the stimulus is conditioned.

Although the respondent conditioning model may seem complex, it is highly useful in establishing strong and consistent responses to certain events. Stimuli can be conditioned to a variety of responses and even emotional reactions. In fact, kindergarten teachers often use this procedure to establish the classroom as a pleasurable and desired environment by filling it with stimuli most children enjoy, thus creating an association between school and fun and increasing the child’s inclination to attend.

Once behavior is learned through respondent conditioning, it can be maintained, reconditioned, reduced through extinction, or generalized. Behavior may also come under the control of operant conditioning contingencies.

Operant Conditioning

In operant conditioning, behaviors are said to operate on and to be changed by the environment. Specifically, particular stimuli are present in a given setting and come to occasion responding, which in turn produces certain stimulus effects. The stimuli present before behavior are referred to as antecedents. Antecedent stimuli function to set the occasion for, or evoke, behaviors in that they signal appropriate times for the individual to emit each behavior. Antecedents gain strength in their ability to evoke responding through their reliable occurrence in the presence of certain consequences. Consequences are stimuli that are produced as a result of behavior and affect the probability that the behavior, and similar responses, will occur again in similar settings. It is a misconception to think of consequences as something to be avoided; rather, they are defined by their ability to influence the occurrence of a particular behavior again in the future. Some consequences increase the likelihood of a response, and some diminish this probability. Either way, consequences are neither good nor bad; they merely help us to make predictions about what we are likely to do and why behavior persists.

Figure 2 The Operant Conditioning Model

Figure 2 The Operant Conditioning Model

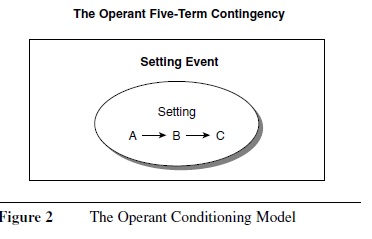

Operant conditioning is described by a five-term model. As seen in Figure 2, the most basic portion of this model is the A-B-C analysis. Antecedents evoke behaviors, which then produce consequences. The evocative function of antecedent stimuli is distinct from the eliciting function of stimuli in the respondent conditioning model. Although both evocation and elicitation rely on stimulus control, the control stimuli exerted in operant conditioning are dispersed across the antecedent stimulus, the setting, the motivation of the learner, the control exerted by competing stimuli, and other factors. Antecedents are said to set the occasion for responding. In this conceptualization, stimuli might be thought of as signals, predictors, or influencing factors, but not causal events.

This A-B-C event occurs in the context of a particular setting and is further influenced by setting events present before the individual enters the setting. Setting events include elements that function to motivate the individual because of states of satiation and deprivation, sometimes called establishing, or motivating, operations.

The operant conditioning model includes four principles of learning: reinforcement, extinction, punishment, and stimulus control. Stimulus control was discussed previously. Thus, the remaining principles will be examined in more detail.

Reinforcement

Reinforcement is the process by which consequences are applied to increase the future probability of a given response. Reinforcement, like all principles of learning, is defined functionally, that is, by the effect that the consequence has on behavior. If a stimulus is presented or removed following the occurrence of a particular behavior, and that behavior occurs again in a similar setting in the future, we would say that reinforcement was in effect. When a pleasant stimulus is presented and behavior reoccurs, then we would say that positive reinforcement has been provided. In the context of this definition, the term positive refers to the presentation of a stimulus immediately following a response and should not be confused with the common use of the word positive to refer to something as good or encouraging. Conversely, when an aversive stimulus is removed following the emission of a behavior and that behavior becomes more likely to occur again in the future, the process is called negative reinforcement. The term negative in this context refers to the removal of a stimulus following a response and should not be confused with the common use of the word negative to refer to something as unpleasant or harmful. In both cases, whether the behavior is changed by the presentation or removal of a stimulus, behavior must always have an increased probability of occurrence following the consequence to be defined as reinforcement. Quite simply, behavior must continue to happen or happen more often after a stimulus follows behavior for reinforcement to have taken place.

When one is attempting to establish a new behavior, it is important to provide a reinforcer following each occurrence of the target behavior. This is called continuous reinforcement, and it facilitates the acquisition of new repertoires by providing a consistent set of consequences for behavior. Once behavior has been established, the schedule of reinforcement can be thinned such that every other behavior, for example, can be reinforced and still maintain a consistent performance on the part of the learner. This thinning of the delivery of reinforcement has the advantage of more reliably approximating the reinforcement delivered in everyday settings. This will facilitate the transition of the learner from a programmed teaching environment to a more natural setting.

An intermittent schedule of reinforcement can be changed in two ways: in a fixed or variable manner. Fixed schedules of reinforcement have a preset amount of behavior that must occur before reinforcement is delivered. In contrast, variable schedules work around an average amount of behavior. Behavior can be measured along the dimensions of ratio, duration, or interval. A ratio schedule requires that a fixed or variable number of responses occur before a reinforcer is delivered. Duration schedules measure the amount of time that a behavior occurs. Interval schedules measure the amount of time between the first behavior and the repetition of that same behavior. Thus, one might use an intermittent schedule of reinforcement to maintain a known behavior on a fixed or variable ratio, duration, or interval schedule.

In common nomenclature, the terms reinforcement and reward are used synonymously. This use is incorrect in that it fails to distinguish the characteristic effect on behavior that reinforcement has. Consider the example of a reward for a lost kitten. This may function as an antecedent for some, but not others, to search for the kitten. A bully might steal the kitten from me and claim the reward; the reward will not change the bully’s searching behavior (although bullying might be reinforced). The behavior of searching may “pay off” if you are the first to bring the correct pet to its owner. Additionally, one must consider that not all stimuli are equally reinforcing to all learners all of the time. If searching happens more often after receiving a monetary reward, then reinforcement of searching behavior has occurred.

Extinction

Once a behavior is conditioned through the use of reinforcing consequences, it can be maintained, changed, diminished through extinction, or generalized. Maintenance is when a behavior persists over time, even after the contingencies that established it are no longer present. A behavior that was once reinforced, such as thumb-sucking in a young child, can later be punished. This change in consequences will change the likelihood of that behavior reoccurring. An operant behavior may be extinguished by withholding or changing the consequence that established it. Withholding reinforcement for a previously reinforced response is referred to as operant extinction.

A common outcome of extinction is an extinction “burst,” or an increase in the previously reinforced response immediately after an extinction procedure has been introduced. Extinction bursts are common because the individual is conditioned to receive a certain reinforcer following a specific response, and when that reinforcer does not follow the response, the individual repeatedly emits the response as in the past to produce the reinforcer. Over time, the rate of the response decreases to zero in the absence of reinforcement. Occasionally, after a period in which the behavior is not observed, it may reemerge. Spontaneous recovery occurs when the individual emits the extinguished response after a period of time has passed from the extinction procedure. If the response still produces no reinforcement, it again is extinguished. A final possible outcome for an established response is that it may generalize to occur in new settings. There are two types of generalization: stimulus generalization and response generalization. In the case of stimulus generalization, a class of functionally similar stimuli can come to evoke a known response. Response generalization occurs when a class of functionally similar responses comes to be evoked by a single known stimulus.

Punishment

Punishment, like the other principles of learning, is defined functionally by its effect on behavior. Punishment is a process that produces a decrease in the probability of that behavior occurring in again the future. Punishment is often mistakenly thought of as something painful, cruel, or at least unpleasant. Although it is true that aversive control is exercised in punishment, that is, stimulus conditions that the learner does not prefer are arranged, the use of punishment should be governed by the highest standards of ethics, and it should always be used as an intervention of last resort.

Punishment can operate in two ways. First, positive punishment is defined as the presentation of a stimulus immediately after a response, which decreases the probability of that response occurring in the future. Some examples of positive punishment include overcorrection, positive practice, and physical restraint. Overcorrection is a punishment procedure that calls for the individual to restore the environment to a more improved state than it was in when the behavior occurred. Positive practice procedures involve requiring the individual to correctly complete a task repeatedly, following an instance of incorrectly performing the task. For example, the individual throws trash in the sink as opposed to the garbage. To reduce the probability of performing the incorrect form of the behavior, a positive practice procedure would involve requiring the individual to repeatedly throw trash in the garbage. Physical restraint procedures are also considered to be positive punishment in that a physical restraint is presented after the behavior to reduce that behavior in future settings.

The removal of a stimulus immediately after a response, which decreases the probability of that response occurring in the future, is the second type of punishment: negative punishment. Time-out and response cost procedures are examples of negative punishment. Time-out procedures involve removing the individual from a reinforcing situation following the target response, or not allowing reinforcement for a specified amount of time following the target response. Response cost is a procedure usually associated with a token economy. A response cost procedure entails removing tokens, or similar items already earned, as a result of an occurrence of the target behavior.

Regardless of the type of punishment used, it must always have the effect of decreasing the probability of that response, and similar responses, in the future. In light of this definition, it is interesting to consider the prison system. Most would consider it a punishment system. However, it can only be punishment if the probability of the criminal behavior that produced the incarceration is decreased. For the many inmates who commit the same crime again following release, prison might be more appropriately defined as a reinforcement system, or one that has no consequential effect on behavior for that learner.

There are many considerations to make before implementing a punishment procedure. Punishment procedures can produce a wide array of side effects. These side effects include negatively reinforcing the behavior of the punisher, aggression, an increase in escape-motivated and avoidance-motivated behaviors, modeling of future punishment behaviors, and ethical conflicts.

Ethics of Punishment

There are many ethical issues associated with the use of punishment procedures in clinical settings. An important rule to remember is that professionals should always be seeking the most effective and efficient strategies to promote the success of the learner that are the least restrictive for the client. Punishment procedures are intrusive by nature, and the client’s fundamental human rights must be carefully considered.

A thorough review of prior intervention plans and reasons for their failure should also be considered when considering the adoption of a punishment procedure. A punishment procedure should have a clear rationale. Informed consent should be obtained before starting any punishment procedure. Meeting with the client or the parent or guardian of the client and reviewing the history of the client and prior methods that have failed to produce a lasting behavior change is part of the process of obtaining informed consent. The proposed punishment procedure should be carefully explained, including possible side effects of the procedure. All of the members of the team should have ample opportunity for questions and suggestions and to experience the punishment procedure themselves. If the individual or parent or guardian demonstrates an understanding of the procedure and provides written consent, the procedure may be put in place under the supervision of a qualified professional. As with any learning program, the learner’s level of behavior before, during, and after the intervention should be carefully measured and constantly evaluated.

Modeling And Imitation

In addition to biological inheritance and respondent and operant conditioning, learning can also occur through the process of modeling and imitation. In social settings where learners are present who have acquired a particular skill, they may demonstrate that behavior in the presence of other learners. Behaviors are more likely to be modeled if there is similarity between the learner and the model, if the consequences of behavior for the model are favorable to the learner, and if the learner has a history of reinforcement for the imitation of the behavior of others. Once a learner performs a behavior, it can be shaped by the environment. Thus, it may be strengthened through reinforcement, weakened through punishment, or changed in other ways by the action of the environment.

Imitation of the behavior of a model may occur immediately, or after a time delay. Models can be present directly to the learner or can appear through other media, including video, books, games, or even verbal descriptions. In some applications of modeling for teaching new skills, the learner may even serve as an appropriate model for later imitation through the use of video recording. Self-modeling has been used in many settings to establish many behaviors.

Principles And Theories

Important distinctions can be made among principles of learning, theories of learning, and learning theorists themselves. The scientific study of how individuals learn has revealed the fundamental principles of learning that govern the behavior of all living organisms. These principles include reinforcement, punishment, extinction, stimulus control, and respondent conditioning.

The study of human behavior has demonstrated that certain patterns of responding can be observed in individuals with similar characteristics when placed in similar types of settings. These consistencies have given rise to a variety of theoretical analyses of learning. Unlike principles of learning, theories of learning may not have universal applicability. However, they may have useful and broad explanatory appeal and often shape social and political policy.

Teaching And Learning

The science of learning is a rich source of information for the design of effective and efficient teaching and learning environments. Learning can be facilitated through the application of sound teaching practices. All learners can benefit from the application of maximally effective practices; although in the case of learners with special needs, the power of remedial and accelerated learning programs is dramatically enhanced by the adoption of teaching and learning practices with demonstrated effectiveness.

Creating learning environments that maximize motivation without being distracting is important. Learners’ unique repertoires of strengths and learning opportunities should be assessed. Individualized curricula, goals, and monitoring programs are appropriate for students of all types. Many classrooms will employ peer groups, learning stations, and carefully selected lessons matched to each student’s repertoire to facilitate simultaneous instruction of learners at the appropriate level.

References:

- Catania, C. (1998). Learning (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Kazdin, E. (2001). Behavior modification in applied settings (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Learning Theories, http://www.emtech.net/learning_theories.htm

- Mazur, E. (1998). Learning and behavior (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.