The Pygmalion effect is a special case of self-fulfilling prophecy (SFP) in which raising a manager’s expectations regarding worker performance boosts that performance. The Pygmalion effect debuted in educational psychology when psychologists experimentally raised elementary school teachers’ expectations toward a randomly selected subsample of their pupils and thereby produced significantly greater gains in achievement among those pupils in comparison to pupils in the control group. Subsequent experimental research has replicated this phenomenon among adult supervisors and subordinates in a variety of military, business, and industrial organizations and among all gender combinations. Both men and women lead both men and women to greater success when they expect more of them. Through the medium of interpersonal expectancy effects in various mentoring relationships, the Pygmalion effect undoubtedly plays a major, albeit largely unheralded, role in career development.

The Pygmalion effect is a special case of self-fulfilling prophecy (SFP) in which raising a manager’s expectations regarding worker performance boosts that performance. The Pygmalion effect debuted in educational psychology when psychologists experimentally raised elementary school teachers’ expectations toward a randomly selected subsample of their pupils and thereby produced significantly greater gains in achievement among those pupils in comparison to pupils in the control group. Subsequent experimental research has replicated this phenomenon among adult supervisors and subordinates in a variety of military, business, and industrial organizations and among all gender combinations. Both men and women lead both men and women to greater success when they expect more of them. Through the medium of interpersonal expectancy effects in various mentoring relationships, the Pygmalion effect undoubtedly plays a major, albeit largely unheralded, role in career development.

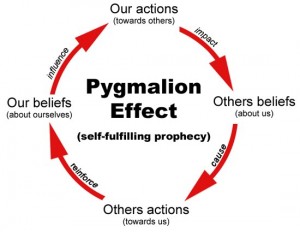

Several theoretical models have been proposed to explain how a leader’s expectations influence subordinates’ performance. Common to all these models is a causal chain that begins with the impact of the leader’s expectations on, and his or her own behavior toward, subordinates, which arouses some perception or motivational response on the part of the subordinates and culminates in subordinate performance in accord with the leader’s expectations. Self-efficacy has emerged as the key motivational variable in this causal chain. Self-efficacy is an individual’s belief in his or her ability to perform successfully. Self-efficacy has been shown to be a key determinant of performance. When individuals believe they have what it takes to succeed, they try harder; however, those who do not believe they can succeed, refrain from exerting the effort that would apply the ability that they do have toward performance, and they accomplish less than they could. The Pygmalion-at-work model posits that having high expectations moves the leader to treat followers in a manner that augments their self-efficacy, which in turn motivates the subordinates to exert greater effort in their work, eventuating in enhanced performance. Thus, the Pygmalion effect is a motivational phenomenon initiated by the high performance expectations held by a leader who believes in followers’ capacity for success. In a largely unconscious interpersonal process, leaders with high expectations lead their followers to success by enhancing their self-efficacy.

The SFP is a double-edged sword: As high expectations culminate in improved performance, low expectations can depress performance in a negative SFP process dubbed the Golem effect. “Golem” means oaf or dumbbell in Hebrew and Yiddish slang. Leaders who expect dumbbells get dumbbells. Another variant of SFP is the so-called Galatea effect. This is an intrapersonal expectancy effect in which self-starters fulfill their own prophecy of success; believing in their own capacity to excel, they mobilize their internal motivational resources to sustain the effort needed for success even without any external source of high expectations. Finally, some research has shown group-level expectancy effects in which a manager’s high expectations for a whole group, as distinct from particular individuals, culminate in that group’s exceeding the performance of groups in the control condition.

A fascinating but elusive aspect of interpersonal SFP involves the communication of expectations. Some of this communication is verbal and conscious, but much of it is not. Teachers and managers exhibit numerous nonverbal behaviors through which they convey their expectations, both high and low, to their pupils and subordinates. When they expect more, they unwittingly smile more, nod their heads affirmatively more often, draw nearer, maintain more frequent and longer eye contact, speak faster, and show greater patience toward those they are mentoring. These nonverbal behaviors serve to “warm” the interpersonal relationship, create a climate of support, and foster success. Other ways in which leaders favor those of whom they expect more include providing them with more input, more feedback, and more opportunities to show what they can do, while those of whom less is expected are left, neglected, “on the bench.”

Meta-analyses have abundantly confirmed the validity of the Pygmalion phenomenon in management as in education. The experimental design of this body of research confirms the flow of causality from leaders’ expectations to follower performance. What remains to be shown is the practical validity of the Pygmalion effect. Although abundant field-experimental replications have produced the effect in military and civilian organizations, attempts to get managers to apply it through managerial training have been less successful. Managers’ prior acquaintance with their subordinates appears to be a barrier to widespread practical application. Virtually all the successful replications have been among newcomers whose managers had not previously known them. Familiarity apparently crystallizes expectations, as managers do not expect their subordinates to change much. Therefore, the most effective applications may be made among managers and their new subordinates. Thus the Pygmalion effect may be most relevant in the early stages of career development. These may be the most important, formative years.

Organizational innovations and other digressions from routine can occasion conditions conducive to Pygmalion effects. For example, when organizational development programs unfreeze standard operating procedure or when the organization undergoes profound change in structure or function, a window of opportunity opens for managers quick of mind and action to piggyback on these unsettling events and raise expectations in order to promote effective change and successful outcomes. In one classic example, the introduction of job rotation and job enrichment produced significant improvements in production when accompanied by information that raised expectations from the new work procedures, but neither innovation produced any productivity improvement when expectations were not raised. The implications for practical application are clear: Change presents managers with opportunities for creating productive Pygmalion effects. It is incumbent upon those who want to lead individuals, groups, and organizations to success to convey high expectations when the opportunity presents itself. Conversely, cynicism or expressions of doubt about reorganization or other potentially disruptive changes condemns them to failure. Thus the practical agenda is twofold: first, managers and other mentors must counteract any manifestations of contrary expectations, and second, they must implant high expectations.

The essence of the Pygmalion effect is that managers get the workers they expect. Generalizing to career management, one can prophesy that one gets the career one expects. Expect more and you will get more. However, the converse is true too: Expect less and you will get less. All the mentors who have a hand in career development can and should play a Pygmalion role by cultivating in themselves high expectations regarding their mentees’ developmental potential and by fostering in the mentees themselves high self-expectations regarding their own potential for success. High expectations are too important to be left to chance or whim; they should be built into all career development programs to make sure they take root.

See also:

- Leadership development

- Motivation and career development

- Self-efficacy

- Self-leadership

References:

- Eden, D. 1992. “Leadership and Expectations: Pygmalion Effects and Other Self-Fulfilling Prophecies in Organizations.” Leadership Quarterly 3:271-305.

- Eden, D. 2003. “Self-fulfilling Prophecies in Organizations.” 91-122 in Organizational Behavior: The State of the Science, 2d ed., edited by J. Greenberg. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Eden, D., Geller, D., Gewirtz, A., Gordon-Terner, R., Inbar, I., Liberman, M., Pass, Y., Salomon-Segev, I. and Shalit, M. “Implanting Pygmalion Leadership Style through Workshop Training: Seven Field Experiments.” Leadership Quarterly 11:171-210.

- McNatt, D. B. 2000. “Ancient Pygmalion Joins Contemporary Management: A Meta-analysis of the Result.” Journal of Applied Psychology 85:314-322.

- Merton, R. K. 1948. “The Self-fulfilling Prophecy.” Antioch Review 8:193-210.

- Rosenthal, R. 2002 “Covert Communication in Classrooms, Clinics, Courtrooms, and Cubicles.” American Psychologist 57:838-849.