The tall, elaborately carved and painted totem pole represents the most famous and well-known type of Northwest Coast art. Images on these carvings depict crests, beings that in some time in the past interacted with a family ancestor and bestowed upon his lineage the right to tell its story and depict its image. Crests were cherished family privileges that embodied family history and contributed to its status. When a family raised a pole that depicted one or several of its crests, it had to sponsor a potlatch to validate this display and pay the witnesses of its presentation of privileges with quantities of goods.

During their early voyages to the Northwest Coast at the end of the 18th century, explorers and traders saw almost no poles. Seaman John Meares sighted one in 1789, and in 1791 John Bartlett drew the earliest known depiction of a totem pole, a 40-foot-high frontal pole in the Haida village of Dadens on Haida Gwaii. Before that time, no traveler had described or illustrated exterior poles. It would only be during the 19th century that villages from the Tlingit to the Kwakwaka’wakw erected large numbers of totem poles.

The totem pole presumably developed from several aboriginal types of monumental art: interior house posts, facade paintings, and mortuary carvings erected out-of-doors. It is likely that the exterior columnar totem pole originated in precontact time among the Haida or Tsimshian. Totem poles were the single most striking type of 19th-century Haida art and increased in numbers from few in early contact times to abundant by the 1860s. While only two stood in Dadens in the late 18th century, by the first decades of the 19th century, large numbers of poles stood in both Haida Gwaii and in the Kaigani region.

Probably the increased wealth and growing competitiveness between chiefs inspired the flourishing of totem poles. Chiefs with greater riches wanted more impressive visual expressions of their high positions, and consequently commissioned taller and more numerous poles. Artists using metal tools they obtained in trade carved larger and more complex works of art. Commercial paints facilitated their decoration. After the northern British Columbia tribes invented the pole, it spread first to the Kaigani region of Alaska, north to the Tlingit, and in the later 19th century, south to the Wakashan groups. By the 1880s, the Haida had virtually ceased carving poles, but it was at around that time that the Kwakwaka’wakw began to erect more and more of them. It is possible that these express an ostentatious disregard for the British Columbia potlatch law, for poles were meaningless without the potlatch that validated their erection.

Poles became widely known outside the Northwest Coast as a result of the combined effects of tourism, world’s fairs, and museum collecting. In the 1880s, steamships brought sightseers up the Inside Passage. Fascinated by the totem poles they saw, tourists placed these monuments among the “must sees” on every itinerary. Poles themselves began traveling to distant places when they were presented at several world’s fairs; in the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, the Smithsonian Institution presented publically its first totem poles. For the 1894 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, Franz Boas assembled an impressive array of poles, which eventually became part of the Field Museum’s collection. And, at the 1904 St. Louis Louisiana Purchase celebration, an impressive array of Alaska totem poles stood before the Alaska building. These ended up returning to Sitka, where copies stand in the National Historic Park there. Other museums collected poles, and by the 1920s, few remained in their originating communities, for many had left for points south and east.

Poles became widely known outside the Northwest Coast as a result of the combined effects of tourism, world’s fairs, and museum collecting. In the 1880s, steamships brought sightseers up the Inside Passage. Fascinated by the totem poles they saw, tourists placed these monuments among the “must sees” on every itinerary. Poles themselves began traveling to distant places when they were presented at several world’s fairs; in the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, the Smithsonian Institution presented publically its first totem poles. For the 1894 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, Franz Boas assembled an impressive array of poles, which eventually became part of the Field Museum’s collection. And, at the 1904 St. Louis Louisiana Purchase celebration, an impressive array of Alaska totem poles stood before the Alaska building. These ended up returning to Sitka, where copies stand in the National Historic Park there. Other museums collected poles, and by the 1920s, few remained in their originating communities, for many had left for points south and east.

In the first several decades of the 20th century, both the Canadian and United States governments recognized the value of totem poles as tourist attractions and supported projects for the restoration of the remaining totem poles that, often decayed and deteriorating, still stood in situ. Instead of disinterestedly allowing these monuments to be taken away and erected in distant museums, efforts began to preserve, restore, and when necessary, copy the originals, now viewed as treasures. Between 1926 and 1930, the Canadian government collaborated with the Canadian National Railway to restore 30 Tsimshian poles along the railroad’s Skeena River route. The Depression-era “Indian New Deal” restoration program propelled Alaskan totem poles into public attention. In 1938, the Indian Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), under the supervision of the U.S. Forest Service, began restoring totem poles, most of which today stand in Ketchikan, the first stop on the ferry from Washington state. Others are in Wrangell and Sitka.

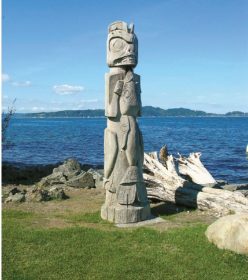

After World War II, the two major British Columbia museums, the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria (originally called the British Columbia Provincial Museum) and the Museum of Anthropology on the University of British Columbia campus in Vancouver, initiated salvage and restoration projects that have become models of cultural preservation. In 1949, the University of British Columbia purchased several Kwakwaka’wakw poles, house posts, and an eleven-piece house frame, which they planned to erect outdoors on the campus. From 1949-1951, Kwakwaka’wakw master carver Mungo Martin was in residence at MOA, restoring his and carving new poles. In the early 1950s, the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria hired Mungo Martin to restore or replicate some of its poles. Over Tony Hunt totem pole, Stanley Park, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada the years, Martin worked with his son David, his adopted daughter’s husband Henry Hunt, Hunt’s son Tony Hunt, and Bill Reid, a man of Haida ancestry who was to become one of the most highly regarded northern Northwest Coast artists.

After World War II, the two major British Columbia museums, the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria (originally called the British Columbia Provincial Museum) and the Museum of Anthropology on the University of British Columbia campus in Vancouver, initiated salvage and restoration projects that have become models of cultural preservation. In 1949, the University of British Columbia purchased several Kwakwaka’wakw poles, house posts, and an eleven-piece house frame, which they planned to erect outdoors on the campus. From 1949-1951, Kwakwaka’wakw master carver Mungo Martin was in residence at MOA, restoring his and carving new poles. In the early 1950s, the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria hired Mungo Martin to restore or replicate some of its poles. Over Tony Hunt totem pole, Stanley Park, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada the years, Martin worked with his son David, his adopted daughter’s husband Henry Hunt, Hunt’s son Tony Hunt, and Bill Reid, a man of Haida ancestry who was to become one of the most highly regarded northern Northwest Coast artists.

After the 1960s, with the reinvigoration of artistic creativity in the region, totem pole carving began to proliferate once more. New poles were raised in a variety of contexts including museums, universities, and Native communities. Among the most well-known living Northwest Coast totem pole carvers are Nathan Jackson (Tlingit), Robert Davidson (Haida), Calvin and Richard Hunt (Kwakwaka’wakw), David Boxley (Tsimshian), and Tim Paul (Nuu-chah-nulth). These and other artists are training younger carvers who will continue the tradition of Northwest Coast totem pole carving.

References:

- Barbeau, M. (1950). Totem poles. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada.

- Garfield, V., & Forrest, L. (1961). The wolf and the raven: Totem poles of southeastern Alaska. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Halpin, M. (1981). Totem poles: An illustrated guide. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Like? Share it!